The Basilica Cistern: The Largest Ancient Underground Cistern In Istanbul

When visiting Istanbul, it’s easy to be captivated by its most iconic landmarks: the Blue Mosque, Hagia Sophia, and Topkapi Palace.

However, beneath the bustling streets of Sultanahmet lies a lesser-known, yet equally fascinating, wonder—the Basilica Cistern (Yerebatan Sarnıcı).

This ancient underground reservoir, often referred to as the “Sunken Palace,” is the largest of several hundred cisterns beneath the city of Istanbul.

It once kept the ancient city supplied with fresh water.

The Cistern Played A Crucial Role In The City’s Water Supply

The Basilica Cistern was built in the 6th century during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Justinian I.

It got its name because it was constructed under a large public square, the Stoa Basilica, on the First Hill of Constantinople (now Istanbul).

This massive underground structure was originally built to store and filter water for the Great Palace of Constantinople, as well as other buildings on the First Hill.

Ancient texts suggest that the cistern was once surrounded by gardens and colonnades, facing the majestic Hagia Sophia.

It’s said that 7,000 slaves were involved in its construction.

The cistern played a crucial role in the city’s water supply, drawing water from the Eğrikapı Water Distribution Centre in the Belgrade Forest, located 19 kilometers north of the city.

The water traveled through a complex system of aqueducts, including the 971-meter-long Valens Aqueduct and the original 115-meter-long Mağlova Aqueduct.

The original basilica was an important center for commerce, law, and art, dating back to the 3rd or 4th century.

After being damaged by fire in 476, it was rebuilt, and later, Emperor Justinian expanded the cistern following the devastating Nika riots of 532.

The cistern played a crucial role in providing water to the Great Palace of Constantinople and, later, to the Topkapi Palace after the Ottoman conquest in 1453.

Remarkably, it continued to supply water to the city for centuries.

Architecture of the Cistern

The Basilica Cistern is about 138 meters long and 65 meters wide, covering an area of about 9,800 square meters.

It can hold up to 80,000 cubic meters of water, which is enough to fill 27 Olympic-sized swimming pools!

The ceiling is supported by 336 marble columns, each 9 meters high, arranged in 12 rows of 28 columns.

These columns are a mix of Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian styles, with most of them being repurposed from older Roman buildings—a practice known as spoliation.

One of the most intriguing features of the cistern is a column decorated with raised images of a Hen’s Eye, slanted branches, and tears, believed to resemble the columns of the Triumphal Arch of Theodosius I.

The columns themselves are carved from various types of marble and granite, adding to the visual diversity of the structure.

The weight of the cistern is carried by these columns, with the roof’s cross-shaped vaults and round arches providing additional support.

The walls of the cistern are 4 meters thick, made of firebrick and coated with a waterproofing mortar to ensure the structure’s longevity.

Fifty-two stone steps descend into the cool, dimly lit chamber, offering a stark contrast to the bustling streets above.

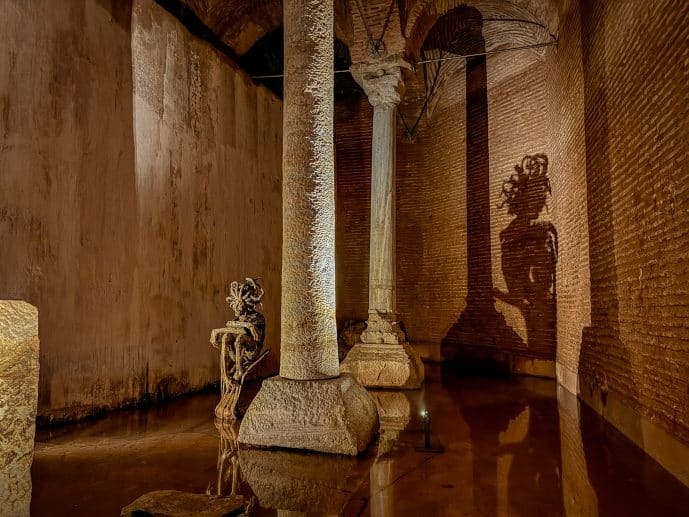

The Mysterious Medusa Heads

At the far end of the cistern, in the northwest corner, lie two enigmatic column bases carved with the face of Medusa, one of the three Gorgons of Greek mythology.

These Medusa heads are placed sideways and upside down, sparking various theories about their orientation.

Some believe that the heads were positioned this way to negate the power of Medusa’s gaze, which could turn onlookers to stone.

Others suggest a more practical reason—that the heads were simply repurposed from another Roman building and placed in the cistern to fit the height of the columns.

The origin of these Medusa heads remains a mystery

Rediscovery and Restoration

For centuries, the existence of the Basilica Cistern was forgotten, except by locals who still drew water from it.

In 1545, a French traveler named Petrus Gyllius rediscovered the cistern when he noticed people lowering buckets into the ground to collect water and even fish.

Gyllius recorded his visit, where he was rowed between the columns and saw fish swimming beneath the boat.

The Basilica Cistern has undergone several restorations since its construction.

The first major repairs were carried out in the 18th century during the reign of Ottoman Sultan Ahmed III, followed by further restoration in the 19th century under Sultan Abdulhamid II.

In 1968, cracks in the masonry and damaged columns were repaired.

In 1985, 50,000 tons of mud were removed from the cistern as part of a large-scale restoration effort by the Istanbul Metropolitan Museum.

Platforms were erected to replace the boats that were once used to tour the cistern, and the site was opened to the public in 1987.

The most recent restoration, which included earthquake-proofing, took place between 2017 and 2022.

Visiting the Basilica Cistern

The Basilica Cistern has one main entrance located near the Hagia Sophia on Yerebatan Caddesi Street.