How The 1904 Marathon Became A Legend Of Chaos In Olympic History

The 1904 Olympics, held in St. Louis, were the first in the U.S. and tied to the World’s Fair, celebrating the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase. The games were poorly organized and overshadowed by the fair, including controversial events like Anthropology Days.

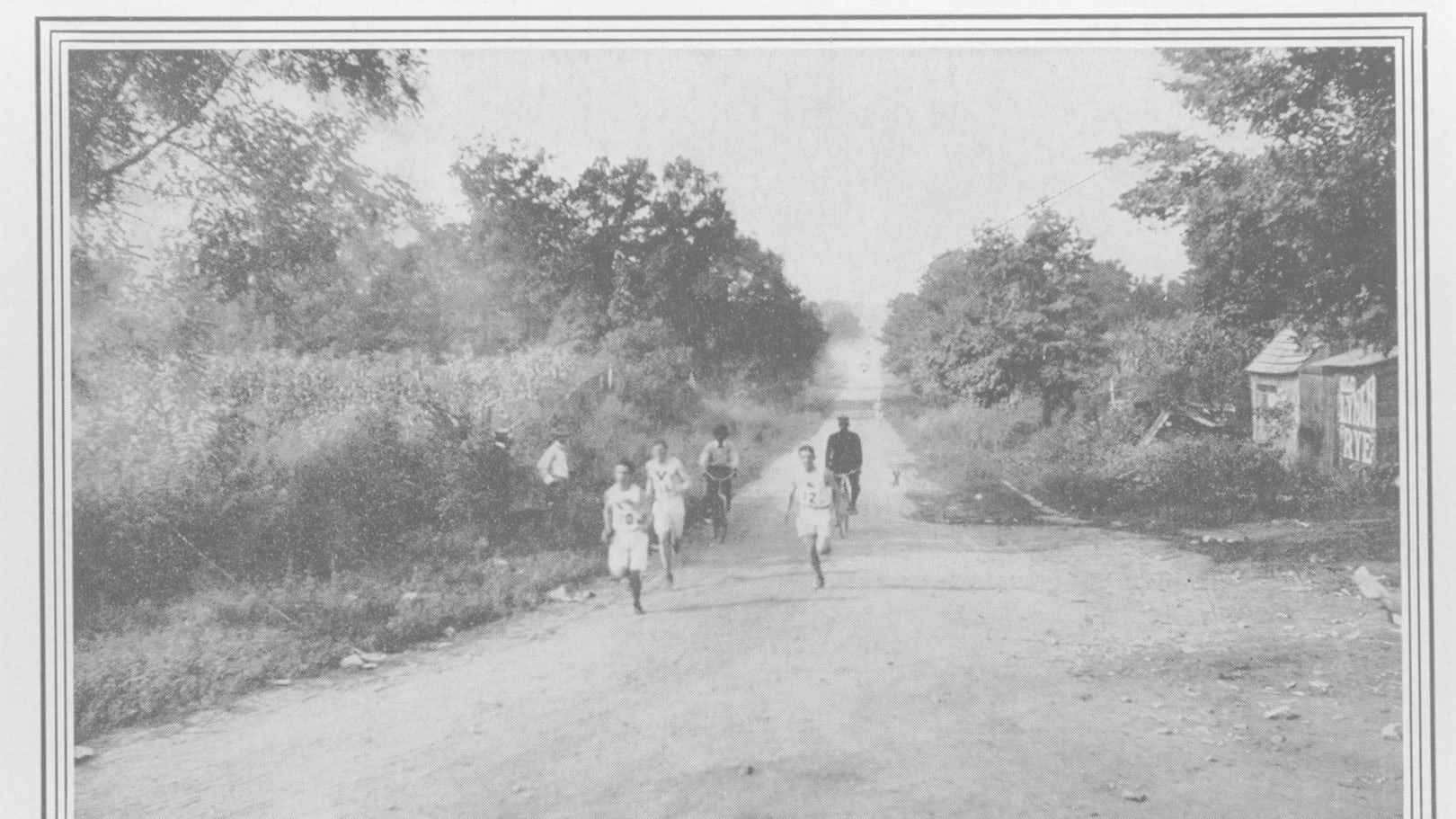

The men’s marathon stood out for its chaos, with unpaved roads, thick dust, and the organizer’s promotion of “purposeful dehydration.” Only 14 of the 32 runners finished, marking it as one of the most bizarre and dangerous races in Olympic history.

Keep scrolling down to explore each event leading up to the marathon and its lasting legacy.

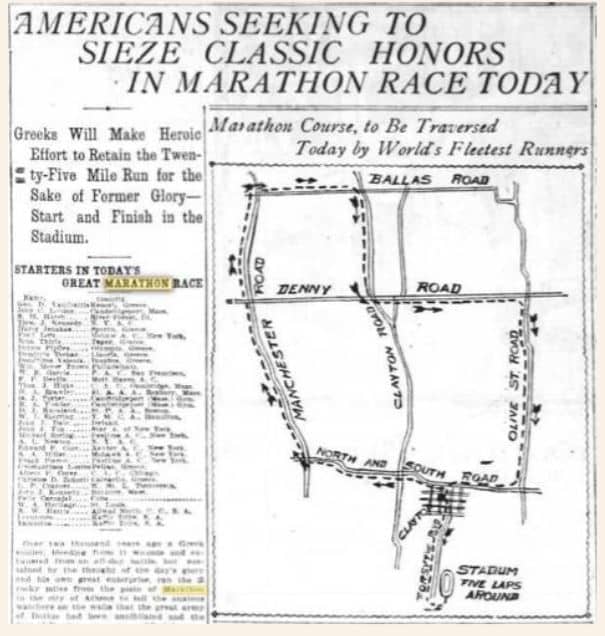

The Marathon featured an unusual cast of runners.

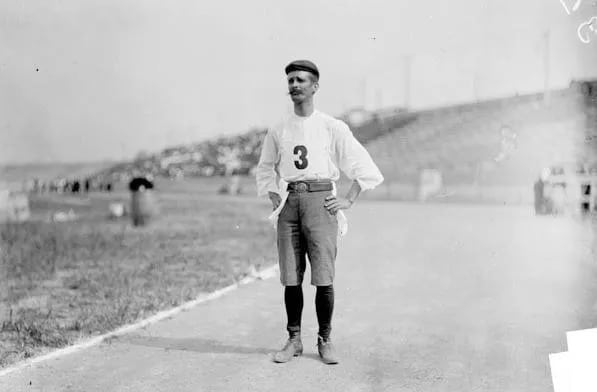

Several runners in the 1904 Olympic Marathon were recognized athletes, including Boston Marathon winners Sam Mellor, A.L. Newton, John Lordon, Michael Spring, and Thomas Hicks.

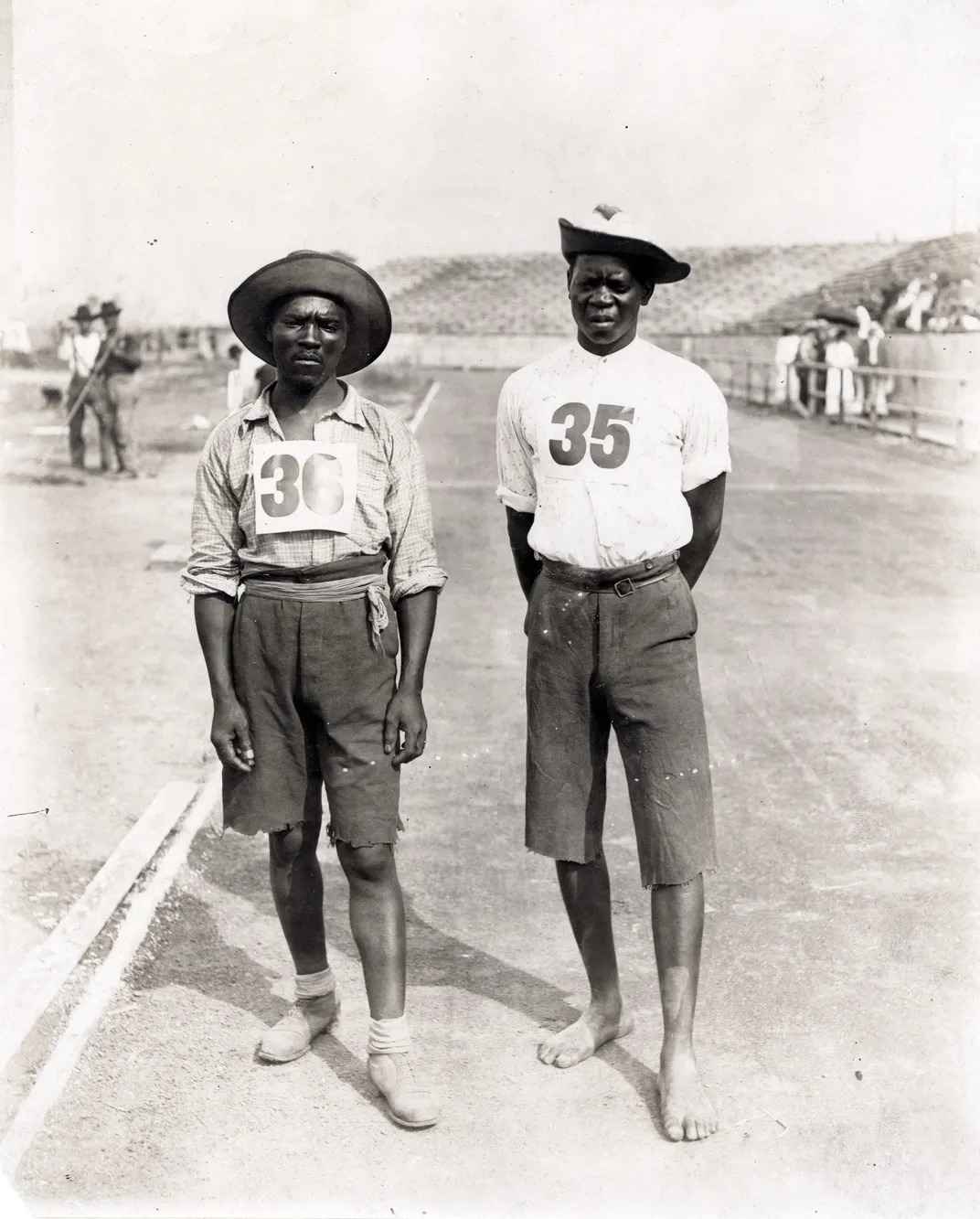

Most runners, however, were middle-distance runners or oddball characters. Fred Lorz, a bricklayer by day, earned his spot in a special five-mile race. South Africans Len Taunyane and Jan Mashiani, the first Black Africans in the Olympics, reportedly ran barefoot.

Félix Carvajal, a Cuban former mailman, raised funds by running across Cuba but lost it gambling, then hitchhiked to St. Louis. He arrived in street clothes, and a fellow runner helped him cut his trousers into shorts.

The poorly organized marathon started at 3:00 pm in extreme heat on dusty roads. Chief organizer James Sullivan limited water stations to study ‘purposeful dehydration.’ The chaotic and dangerous race almost led to its removal from future Olympics.

The first “winner” was disqualified for hitching an 11-mile ride.

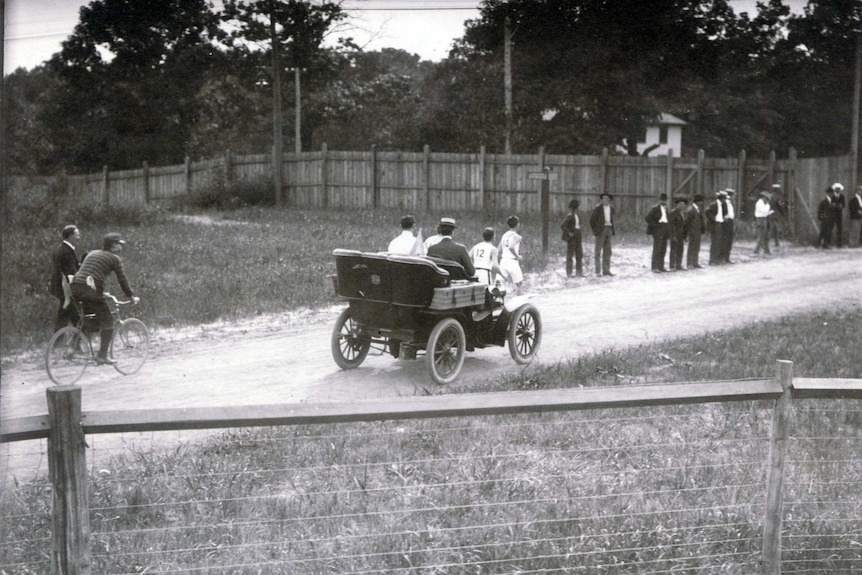

Fred Lorz crossed the finish line first and was about to receive his trophy from Alice Roosevelt when a spectator “called an indignant halt to the proceedings with the charge that Lorz was an impostor.” Lorz had suffered cramps at the 9-mile mark and hitched a ride for 11 miles.

Runner William Garcia collapsed, needing emergency surgery due to ingesting dust. Historian Nancy J. Parezo wrote in The 1904 Anthropology Days and Olympic Games, “He had ingested so much dust that it had ripped his stomach lining.”

The harsh conditions caused many to quit. As the heat and lack of water took their toll, many runners gave up.

Lorz’s disqualification shocked spectators. Lorz explained he had only crossed the finish line as a joke after his trainer’s car broke down, causing an uproar among officials and spectators. With Lorz disqualified, the crowd anxiously waited for the next runner.

The official winner finished high on rat poison.

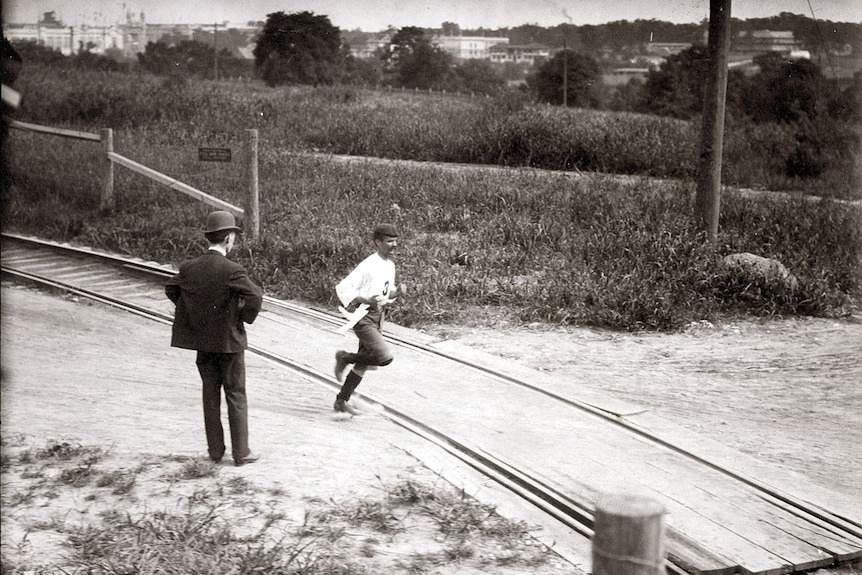

14 kilometers from the finish line, American runner Thomas Hicks was in terrible pain. He tried to lie down, overcome by the dust and heat.

His trainers, wrongly believing water would harm his performance, gave him a toxic mix of rat poison, egg whites, and brandy. Hicks continued to stagger along while being high and hallucinating.

“Denied water, except for being sponged in hot water heated by a car radiator, Hicks lost eight pounds (3.6kg),” Nancy J. Parezo said.

The initial dose of the concoction gave him a boost, according to Olympic historian Bill Mallon. However, a second dose at the 32-kilometer mark was less effective.

Charles Lucas, a race official, described Hicks’s last two miles: “His eyes were dull, lusterless; the ashen color of his face had deepened; his arms appeared as weights well tied down; he could scarcely lift his legs, while his knees were almost stiff.”

In his delirious state, Hicks believed he still had 20 miles to run. His trainers had to carry him, with his legs moving as if he were still running. He finished in 3 hours 28 minutes, wandering the stadium in a stupor and forgetting to collect his medal.

This was one of the slowest Olympic marathon times compared to Eliud Kipchoge’s win in just over two hours at the 2016 Rio Games.

Runners battled wild dogs and rotten apples on the course.

Cuban runner Carvajal jogged in his heavy shoes and loose shirt, making good progress despite stopping to talk to fans in simple English.

According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, their car “passed the little Cuban three miles out, still running steadily, and he waved his cap and shouted enthusiastically,” as reported the next day.

His wild time in New Orleans and rushed trip to St. Louis for the marathon meant he hadn’t eaten in nearly 40 hours.

Once, Carvajal halted near a car where people were eating peaches and asked for one. When they refused, he jokingly took two and ate them while running.

Later on, he stopped at an orchard and had some apples. “Hungry and without any coaches to help him, he grabbed a green apple from a tree along the way,” sports historian Thomas F. Carter wrote in his book, Olimpismo.

But the rotten apple gave him painful stomach cramps, so he took a short nap by the roadside before continuing the race. The determined Cuban pushed through and still managed to finish in fourth place.

Meanwhile, Len Tau, a South African runner, had shown himself to be quite skilled and was in a good position until he was chased a mile off course by a pack of feral dogs. He placed ninth of the 14 finishers.

The aftermath and legacy of this event profoundly influenced future Olympic races.

Thirty-two runners started the 1904 Olympic marathon, but only 14 finished, the lowest number in Olympic history. The race was so disastrous that it almost got cut from the 1908 Olympics. Thomas Hicks declared, “The terrific hills simply tear a man to pieces.”

Fred Lorz received a lifetime ban for cheating but was reinstated after a year once it was found that he didn’t intend to defraud. He continued to race in future events and later won the 1905 Boston Marathon, using only his legs this time.

Felix Carvajal, presumed dead after missing the 1906 Athens marathon, surprised everyone by returning to Havana in 1907.

The winner, Thomas Hicks, continued running marathons before retiring and moving to Winnipeg with his brothers in 1909.

James Sullivan opposed including the marathon in future events, calling it “indefensible.” Despite this, the marathon continued and improved over time.

Dr. Christian Wacker, President of the International Society of Olympic Historians, noted, “The early Olympic Games were a process of discovery. Rules and regulations were only developed and improved over the decades.”

By the 1908 London Olympics, the marathon distance was standardized to 42.195 kilometers, and aiding runners became a disqualifying offense. However, distrust of water continued, with runners using substances like rat poison and brandy for performance enhancement.

John Hayes, the 1908 marathon winner, credited his victory to using cologne and brandy.

The chaotic 1904 marathon helped shape future running events with better routes, start times, and more water stations. Though it was a sideshow to the World’s Fair, its impact on Olympic history remains significant.