Roman Baths: A Well-Preserved Historical Site Dating Back To Roman Britain

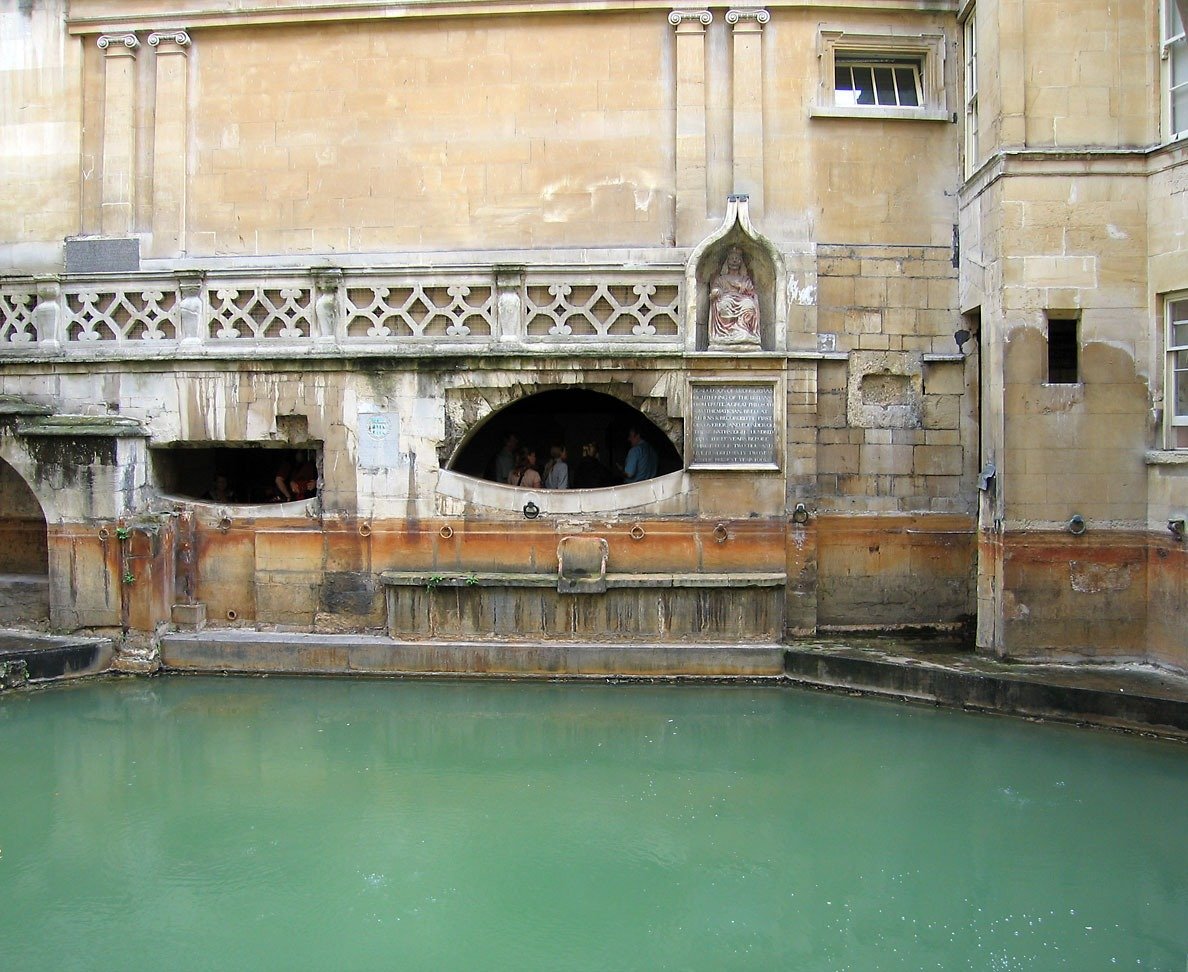

The Roman Baths are one of the best-preserved ancient sites in the city of Bath, Somerset, England.

These baths, or thermae, were built around natural hot springs that have been used for thousands of years.

They are among the most famous Roman sites in the world, attracting over 1.3 million visitors annually.

The Origins of the Roman Baths

The origins of the Roman Baths date back to the first few decades of Roman Britain, between 60 and 70 AD.

During this period, the Romans constructed a temple on the site.

The temple was dedicated to the goddess Sulis Minerva, who was believed to have healing powers.

The Romans identified Sulis with their goddess Minerva, and the town that grew around the temple became known as Aquae Sulis, meaning “the waters of Sulis.”

The baths were constructed over several centuries, with the bathing complex gradually expanding around the sacred spring.

The Romans engineered a sophisticated system to channel the hot spring water into a series of baths for public use.

These included the caldarium (a hot bath), the tepidarium (a warm bath), and the frigidarium (a cold bath).

The complex served as a place for relaxation, socializing, and worship until the end of Roman rule in Britain in the 5th century AD.

The Sacred Spring

The Roman Baths are preserved in four main features: the Sacred Spring, the Roman Temple, the Roman Bath House, and the museum that houses artifacts from Aquae Sulis.

At the heart of the baths is the Sacred Spring, a natural hot spring that has been bubbling up from the earth for thousands of years.

The water comes from rain that falls on the nearby Mendip Hills, which then seeps through the limestone rock, heating up as it descends to great depths.

When the water rises back up through cracks in the rock, it emerges at a temperature of about 46°C (114.8°F), bringing with it a high concentration of minerals.

The Sacred Spring was central to the religious significance of the site.

The Romans believed that the spring was a gift from the gods, and they built a large stone reservoir to contain the sacred water.

Offerings, such as coins and other valuable items, were often thrown into the spring by worshippers seeking the favor of the goddess Sulis Minerva.

This reservoir formed the basis of the Great Bath, the largest of the bathing pools, which was covered by an arched roof while the Temple remained open to the sky.

The Roman Bath Complex

The Roman Baths complex is made up of several key areas:

The Great Bath:

This is the largest and most famous of the baths, where visitors in Roman times would have gathered to bathe and socialize.

It was originally covered by a high, arched roof, but today it is open to the sky.

The Roman Temple:

The temple was built in the center of a large courtyard and is dedicated to Sulis Minerva.

The temple’s entrance was adorned with a pediment featuring a central image, which is often interpreted as a Gorgon’s head or a depiction of a water god.

The temple was a focal point for worship and rituals.

The Museum:

The on-site museum displays many artifacts recovered from the baths, including more than 12,000 Roman coins and a gilt bronze head of the goddess Sulis Minerva.

Post-Roman Times

After the Romans left Britain, the baths gradually fell into disrepair.

By the 6th century, the complex was mostly in ruins, with the sacred spring and baths becoming buried under silt and debris.

However, the hot springs continued to attract visitors, and during the Middle Ages, the site was redeveloped several times.

In the 12th century, a curative bath was built over the spring, and by the 16th century, new baths were constructed, including the Queen’s Bath.

The Baths Today

The Roman Baths as we see them today are largely a result of 19th-century reconstruction.

The buildings at street level, including the Grand Pump Room, were designed by architects John Wood, the Elder, and John Wood, the Younger, and are fine examples of Georgian architecture.

The baths are no longer used for bathing due to health concerns.

However, visitors can explore the site, learn about its history, and view the well-preserved remains.

The water quality is closely monitored by Bath and North East Somerset Council, ensuring the safety of the springs.

However, in 1978, a young girl tragically died after contracting a rare infection from the water, leading to the closure of the baths for several years.

Today, modern bathers can experience the natural thermal waters at the nearby Thermae Bath Spa, which uses a separate, safe supply of water.