5 Love Stories Of Famous Couples That Will Show You How Love Can Make The World Go Round

You know, love between famous couples has really changed things in a big way. I mean, it’s not just about hearts and flowers.

Take Marie and Pierre Curie, for example. They weren’t just in love; they were scientists who made groundbreaking discoveries that shaped our world. And then there’s Richard and Mildred Loving, who fought against laws that kept people apart because of their race. These stories show us how love can make a real difference, not just in people’s lives, but in the world around us.

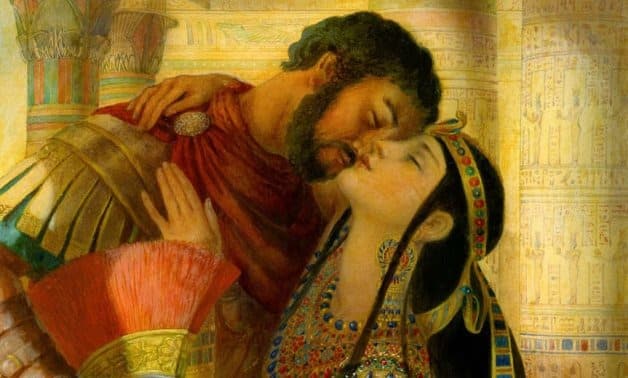

#1. Cleopatra and Mark Antony

Cleopatra VII of Egypt is famous for her legendary powers of seduction and ability to build alliances. She fell in love with a Roman general named Mark Antony. Their relationship caused problems, leading to their deaths and the end of Cleopatra’s family dynasty.

In 41 B.C., Antony accused Cleopatra of aiding his enemies. Cleopatra arrived in a grand boat dressed as Venus, the Roman goddess of love, just like she did with Julius Caesar to win him over. Antony promised to protect Egypt and her crown.

But the next year, he later went back to Rome to marry the half-sister of his co-ruler, Octavian, to prove his loyalty. Cleopatra, meanwhile, gave birth to Antony’s twins and continued to rule over an increasingly prosperous Egypt.

Later, Antony returned to Cleopatra and declared her son Caesarion as the rightful heir of Julius Caesar. This angered Octavian, who was ruling Rome with Antony. Octavian accused Antony of being controlled by Cleopatra and would abandon Rome to found a new capital in Egypt.

In 32 B.C., Octavian started a war against Cleopatra, and in 31 B.C., his soldiers defeated Antony and Cleopatra in the Battle of Actium.

The next year, Octavian went to Alexandria and defeated Antony once again. After the battle, Cleopatra hid in the mausoleum she had built for herself. Antony, mistakenly thinking Cleopatra was dead, killed himself.

On August 12, 30 B.C., Cleopatra, grieving for Antony, ended her own life in her chamber with two of her servants. As she wished, Cleopatra was buried with Antony. Octavian, who later became Emperor Augustus I, celebrated his victory over Egypt and strengthened his rule in Rome.

#2. Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn

Historians believe several factors led England to become Protestant, and one of them was Henry VIII’s infatuation with Anne Boleyn. By 1525, Henry was tired of his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, because she couldn’t give him a son.

His infamously restless gaze finally settled on Anne, a shrewd and exquisite lady-in-waiting whose father was a driven diplomat and knight. Unlike the other women he pursued, Anne refused to be intimate without marriage. When Pope Clement VII refused Henry’s request to annul his marriage to Catherine in 1527, Henry decided to break away from the Catholic Church and marry Anne in secret in 1533.

But Henry’s love for Anne didn’t last long, especially when she couldn’t provide him with a son. In 1536, he had Anne arrested and executed on false charges. He quickly married another woman, Jane Seymour.

This turmoil over religion continued even after Henry’s death. It wasn’t until Henry’s daughter, Elizabeth I, ruled for 44 years that Protestantism became the official religion in England.

#3. Czar Nicholas II and Alix of Hesse

Their story could rival any dramatic opera, set during a time of revolutionary turmoil and featuring a mystical figure and a devastating illness.

Alix Victoria Helena Louise Beatrice, later known as Alexandra Feodorovna Romanov, was the granddaughter of England’s Queen Victoria. Against her family’s wishes that she marry her first cousin, Prince Albert Victor, she chose to marry Nicholas, the heir to the Russian throne.

Nicholas also convinced his ailing father to agree to their union. And finally, they had a wedding in November 1894, just several weeks after the czar’s death and Nicholas’ coronation.

Their marriage, though born from sorrow as it followed the death of Nicholas’ father, was full of love and produced five children, including a son named Alexei. Unfortunately, Alexei inherited hemophilia from his mother, causing his parents great worry. They turned to Grigori Rasputin, a controversial mystic whose treatments seemed to help Alexei.

Rasputin’s influence over the royal couple weakened public trust in the Romanov dynasty and contributed to their downfall during the February Revolution in 1917. Ultimately, Nicholas, Alexandra, and their children were executed on Bolshevik leader Lenin’s orders in 1918, marking a tragic end to their romance and ushering in a new era of bloodshed in Russia.

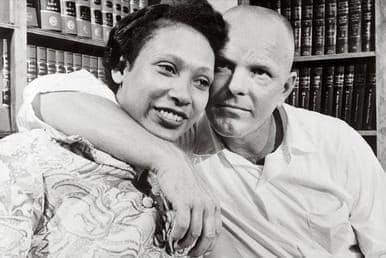

#4. Mildred and Richard Loving

Richard Loving, a white man, fell in love with Mildred Jeter, who was of African and Native American descent, when they were teenagers.

In June 1958, because their home state of Virginia had “anti-miscegenation” laws that made interracial unions illegal, the couple decided to drive 80 miles from Virginia to Washington, D.C., to get married.

Just five weeks after their wedding, police knocked on the door of the newlyweds’ house in the middle of the night to arrest them for being married and living together.

When a sheriff questioned what he was “doing in bed with this lady,” Richard, 24, pointed at the marriage certificate that was hanging on the wall. The couple was given two choices: go to prison or be expelled from Virginia for 25 years. They consequently chose to move to Washington. There, they had three children.

In 1963, they reached out to the government for help and were connected with lawyers from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). The lawyers took their case to the Supreme Court, which ruled in their favor in 1967. The court decided that banning interracial marriage was against the Constitution.

Richard died in a car accident in 1975, but Mildred stayed in the house Richard had built until she passed away in 2008.

#5. Pierre and Marie Curie

Marie Sklodowska and Pierre Curie got married in 1895 and became a famous team of scientists who had an international impact on future generations of scientists.

Marie, born in Poland in 1867, graduated from the Sorbonne in Paris with degrees in mathematics and physical sciences. Eight years later, in 1894, she met her senior, Pierre Curie, who was a renowned French scientist and physicist. The couple shared a love for science and cycling, and they got married one year later.

After hearing about Henri Becquerel’s accidental discovery of radioactivity in 1896, Marie became interested in it. She started researching uranium rays as a topic for her PhD thesis. Pierre quickly joined her in her investigations.

In 1898, they found two new elements, polonium and radium. The year their daughter, Irène, arrived.

Polonium was named for Marie’s native country. They were able to successfully separate radioactive radium salts from pitchblende in 1902. The pair and Becquerel split the physics Nobel Prize the following year in recognition of their revolutionary research on radioactivity.

In 1904, Pierre was appointed to the Sorbonne chair of physics, and Marie gave birth to a second daughter. Tragically, Pierre died in an accident on a Paris street in 1906. Despite her grief, Marie continued their work and became a professor at the Sorbonne, the first woman to do so. She also explored how radioactive substances could help treat cancer.

Marie passed away in 1934 from leukemia caused by exposure to radiation. Their daughter, Irène, also became a scientist and won a Nobel Prize with her husband for their work on radioactivity in 1935.