Anne Morrow Lindbergh: The Great Woman History Forgot

Anne Morrow Lindbergh, often overshadowed by her famous husband Charles, was a remarkable woman in her own right.

As an American author and aviator, she made significant contributions to literature and aviation. Her writings covered diverse topics such as youth, love, peace, solitude, and the changing role of women in the 20th century.

One of her most celebrated books, “Gift from the Sea,” explores the challenges and insights of American women’s lives, offering reflection and inspiration. In 1929, she became the first woman in the United States to obtain a glider pilot’s certificate, marking a turning point in the field.

Join us as we uncover the inspiring journey of this extraordinary woman.

Anne hailed from a distinguished lineage

Anne Spencer Morrow was born on June 22, 1906, in Englewood, New Jersey. Her father, Dwight Morrow, was a partner at J.P. Morgan & Co. and later became a U.S. Ambassador and Senator. Her mother, Elizabeth Cutter Morrow, was a poet and teacher involved in women’s education and served as acting president of Smith College.

Anne, the second of four children, grew up in a Calvinist home that valued achievement. Her mother read to them nightly, fostering a love for reading and writing early on.

Anne attended the Dwight School for Girls and graduated from The Chapin School in 1924. She then earned a Bachelor of Arts degree from Smith College in 1928.

At Smith, Anne received the Elizabeth Montagu Prize for her essay on 18th-century women and the Mary Augusta Jordan Literary Prize for her fiction piece “Lida Was Beautiful.”

The shy Anne Morrow was enamored with the famous aviator Charles Lindbergh

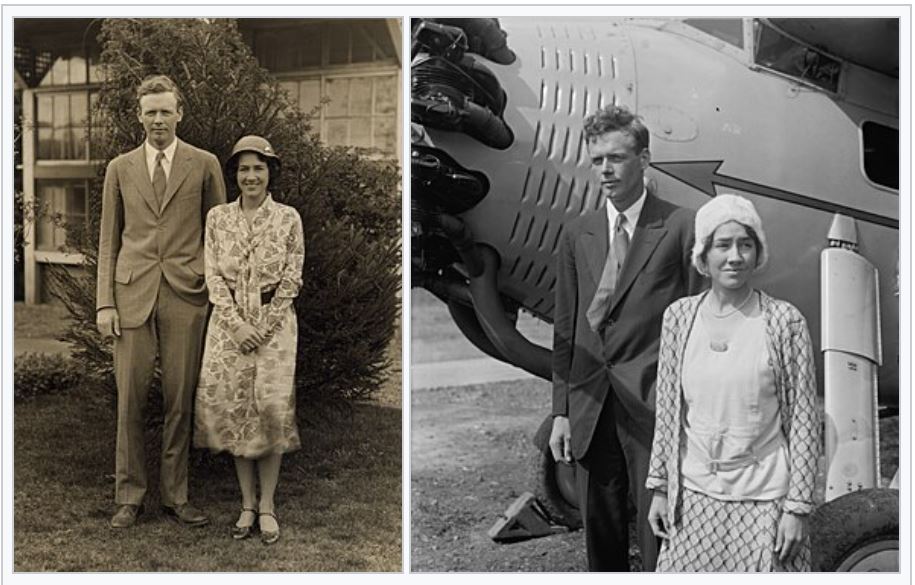

Morrow and Lindbergh met on December 21, 1927, in Mexico City. Her father, Lindbergh’s financial adviser, had invited Lindbergh to Mexico to strengthen the U.S.-Mexico relations.

At that time, Anne Morrow was a 21-year-old senior at Smith College. She was captivated by Lindbergh’s contemplative nature and adventurous spirit.

Lindbergh, a famous aviator, had become a hero after his solo Atlantic flight. He received over 100,000 congratulatory telegrams, including many marriage proposals.

The sight of the boyish aviator staying with her family tugged at Anne Morrow’s heartstrings. She later wrote in her diary:

“He is taller than anyone else—you see his head in a moving crowd and you notice his glance, where it turns, as though it were keener, clearer, and brighter than anyone else’s, lit with a more intense fire…. Anything I might say would be trivial and superficial, like pink frosting flowers. I felt the whole world before this to be frivolous, superficial, ephemeral.”

Their love grew as Lindbergh taught Anne to fly. They married in a simple ceremony at the Morrows’ estate in Englewood, New Jersey, on May 27, 1929, when Anne was 23.

Anne later noted in her diaries, “The man I was to marry believed in me and what I could do, and consequently I found I could do more than I realized.., “

Anne’s life took a dramatic turn after marriage

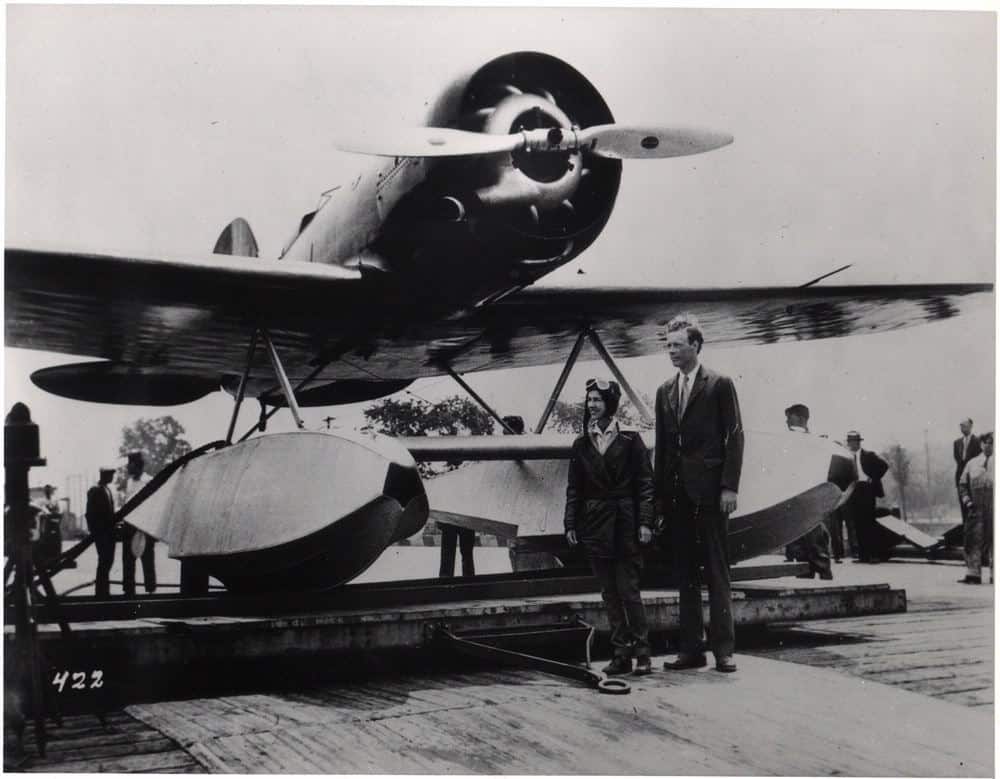

That year, Anne Lindbergh achieved her first solo flight, and by 1930, she made history as the first American woman to obtain a first-class glider pilot’s license. Throughout the 1930s, Anne and Charles Lindbergh undertook pioneering flights, charting new air routes between continents.

They became the first to fly from Africa to South America and ventured along polar routes connecting North America to Asia and Europe.

The 1931 flight over Canada, Alaska, Japan, and China inspired Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s first book, “North to the Orient”. She went on to write over a dozen more books.

Anne’s dedication to aviation went beyond mere interest. In 1934, she received the prestigious Hubbard Gold Medal from the National Geographic Society for her remarkable feat of flying 40,000 miles over five continents alongside her husband.

Additionally, she was honored with the Cross of Honor from the U.S. Flag Association for her contributions to transatlantic air route surveys.

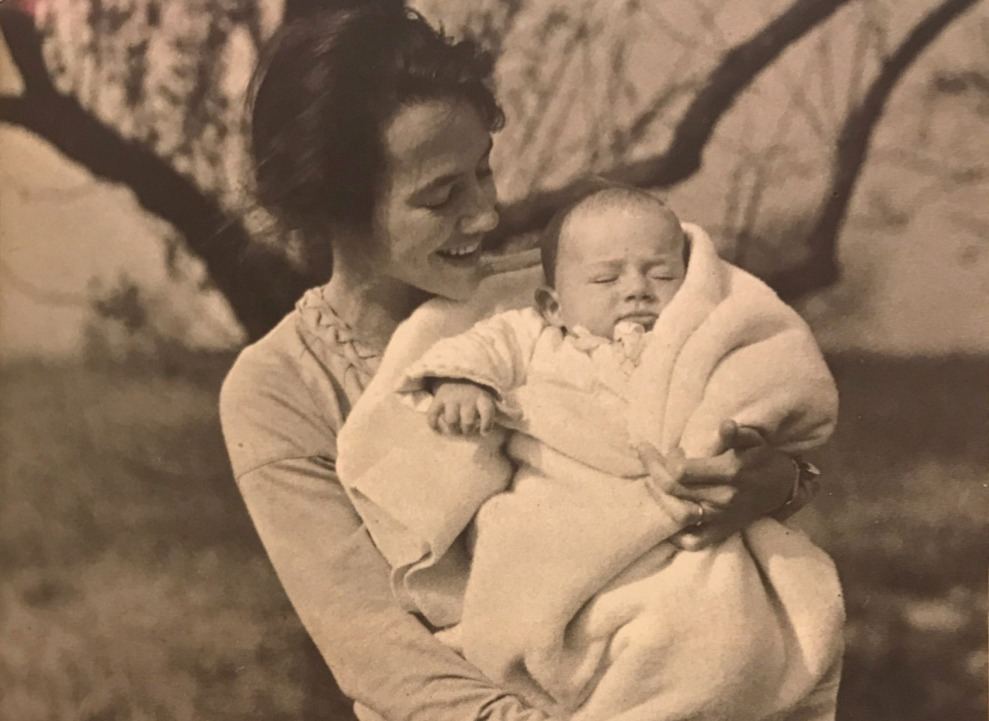

However, their marriage faced severe challenges, most notably the kidnapping and murder of their first son, Charles Jr., in 1932. Despite a $70,000 ransom, their son was killed, and Bruno Richard Hauptmann was convicted. This “Trial of the Century” led to the “Lindbergh Law,” making interstate kidnapping a federal crime.

This tragedy thrust them into the spotlight, bringing both sympathy and intense media scrutiny. To escape media attention, the Lindberghs moved to Europe in 1935, returning four years later.

Despite these hardships, Anne supported Charles’s career while also focusing on her writing. Anne kept detailed daily journals, which sustained her during this traumatic time.

Anne’s literary career was deeply impactful

After World War II, Anne distanced herself from politics and focused on writing poetry and nonfiction, helping to restore the Lindberghs’ tarnished reputation.

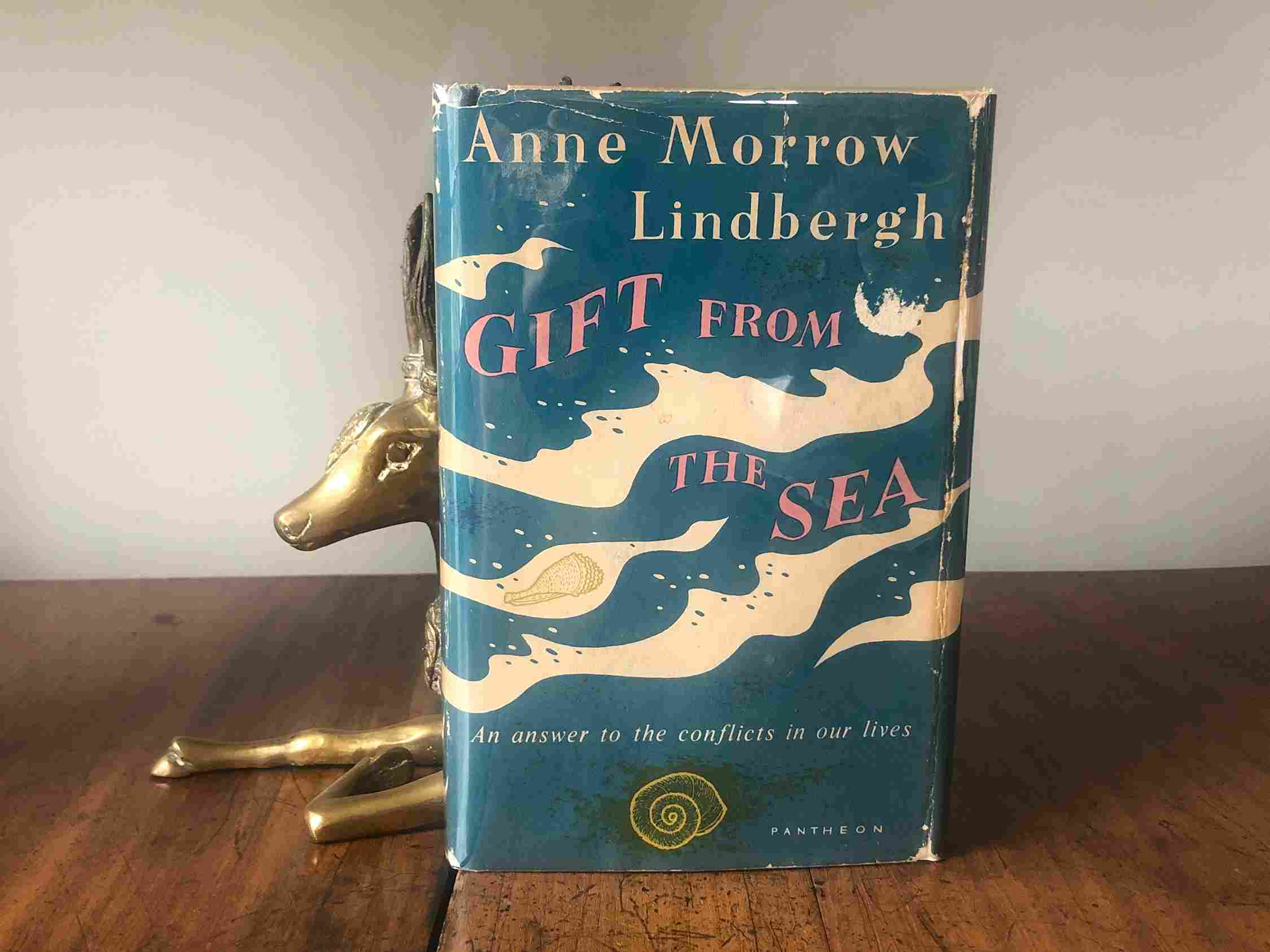

Her book Gift from the Sea (1955), a collection of essays on the challenges faced by women in the modern world, became a bestseller and remains influential.

This collection used seashells as metaphors to explore the stages of a woman’s life, promoting self-discovery, inner peace, and simplicity. Celebrated for its timeless wisdom, it continues to inspire, especially women, with its thoughtful and graceful prose.

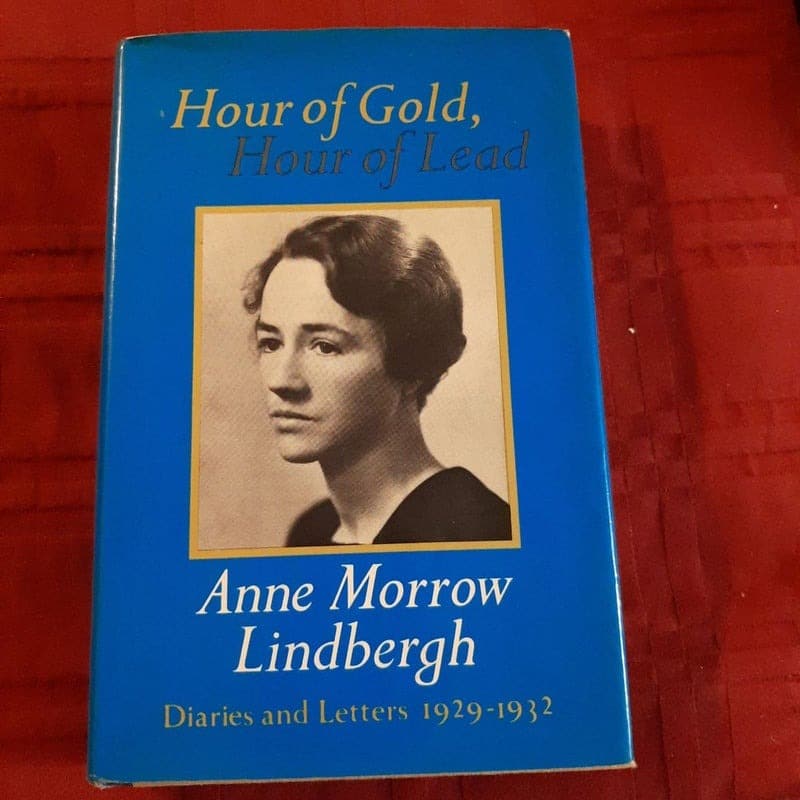

Anne’s later works, like “Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead”, a collection of her diaries and letters, offer a deep look into her life during both happy and challenging times.

Anne Lindbergh’s writing explored themes of human existence and personal growth. She valued solitude and reflection, advocating for a balance between daily demands and personal tranquility. Her works encouraged women to seek fulfillment and assert their individuality in a changing world.

Anne’s life continued after Charles’s death

Throughout their 45-year marriage, the Lindberghs lived in various places, including New Jersey, New York, the UK, France, Maine, Michigan, Connecticut, Switzerland, and Hawaii. Charles passed away in Maui in 1974.

After Charles’s death, Anne continued writing and received honorary degrees from Smith College and Amherst College. She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame and the National Aviation Hall of Fame.

Anne reportedly had a three-year affair with her doctor in the early 1950s. Unbeknownst to her, Charles led a double life from 1957 until his death, fathering seven children with three women in Germany.

In the early 1990s, Anne suffered strokes that left her disabled. She continued living in Connecticut with caregivers. After contracting pneumonia during a visit to her daughter Reeve in 1999, she moved to Vermont, where she died in 2001 at age 94.