7 Less-Known Facts About Henry Adams

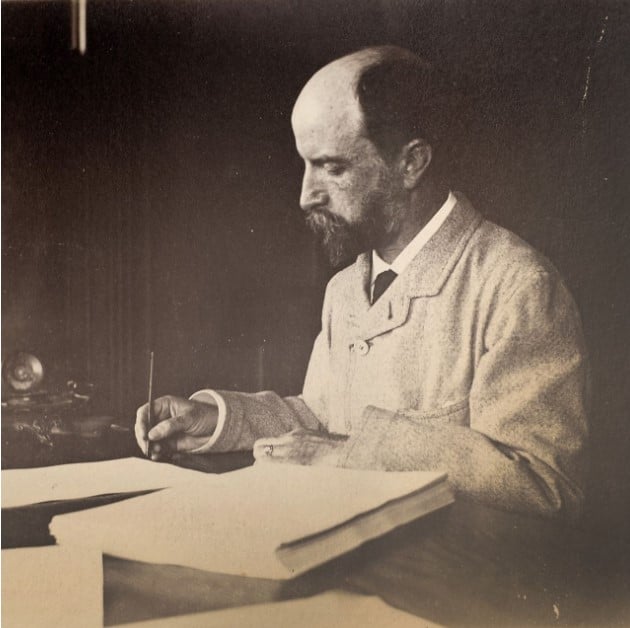

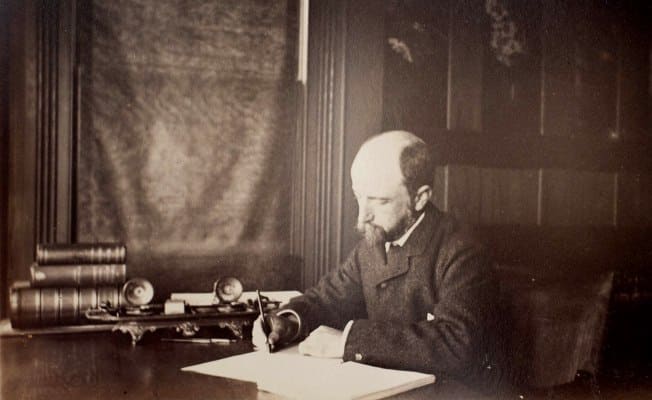

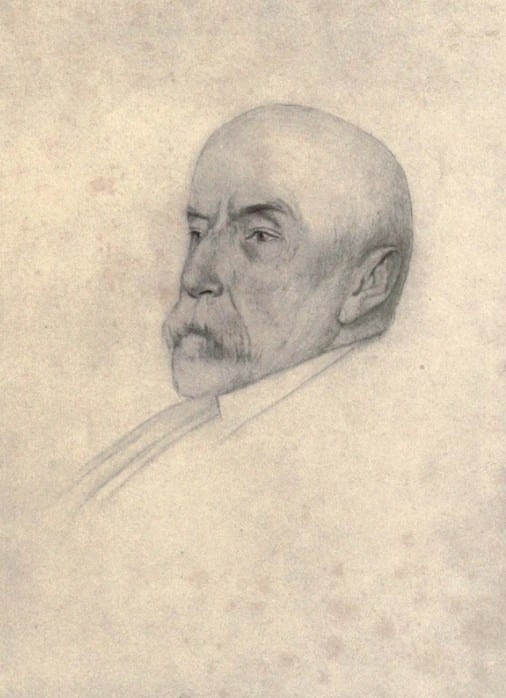

Today, we remember Henry Adams, a distinguished American historian, writer, and member of the famous Adams family. Grandson of President John Quincy Adams, he is best known for his reflective autobiography, “The Education of Henry Adams.”

Despite his political lineage, Henry made his mark in literature and academia, profoundly influencing historical scholarship. His insights into history and society remind us of the ever-evolving nature of our world.

1. Henry Adams had a little club with its own stationery, John Hay, and tea service, King

While living in Washington, D.C., Henry Adams and his wife, Marion Hooper “Clover” Adams, formed a close friendship with Clarence King and Clara and John Hay. King, a geologist, secretly had an African-American wife in New York City, while Hay, Abraham Lincoln’s biographer, would later serve as secretary of state under Presidents McKinley and Roosevelt.

Adams met Hay in 1861 when they were both working in Washington – Adams as his father’s personal secretary and Hay as Lincoln’s. Adams introduced King to the group in 1871, and they frequently gathered at Adams’ home after they moved to Washington in 1877. Adams and Hay were so close that they built adjoining houses near the White House, now the site of the Hay-Adams Hotel. In 1881, they called themselves the Five of Hearts, with Clara Hay being the youngest at 32.

John Hay had stationery printed with a five of hearts monogram, used by the club members for their correspondence. King commissioned a tea service with the same motif and a clock face set to 5 p.m., symbolizing their tea time.

The group’s circle included many notable figures of their time: Mark Twain, Henry James, Walt Whitman, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Henry Hobson Richardson, William Dean Howells, Edith Wharton, Rudyard Kipling, and Andrew Carnegie, as well as every president from Lincoln to Roosevelt.

2. He didn’t include his wife in his autobiography

Henry Adams had married Clover on June 27, 1872, at her father’s home in Beverly Farms, Massachusetts. He often said he was madly in love with her. Tragically, in 1885, Clover Adams died by suicide after struggling with depression as she drank the same chemicals she used to develop photographs.

Clover’s death left Henry Adams consumed by grief, guilt, and the stigma surrounding suicide. In his 467-page autobiography, The Education of Henry Adams, he never once mentioned Clover or their 12-1/2 years of marriage. He described her death as having “smashed the life out of him.”

Before her tragic end, Henry led a relatively stable life. However, after her death, he began to travel extensively, seeking solace in distant places like Japan, Hawaii, the South Seas, Mexico, Egypt, Britain, Cuba, and Europe. His journeys were a way to escape the pain and loss he felt so deeply.

Henry Adams commissioned Augustus Saint-Gaudens to create a bronze sculpture to mark his wife Clover’s grave in Rock Creek Park, Washington, D.C. He suggested Saint-Gaudens draw inspiration from Buddhist devotional art. The resulting statue, symbolizing nirvana, represented a state beyond joy and sorrow.

Adams wrote that the sculpture was meant to pose a question, not provide an answer. The statue became known as “Grief” among tourists, though Adams despised this name. Officially, it’s called the “Adams Memorial,” and it remains a powerful and contemplative piece of art, drawing visitors to reflect on its serene yet enigmatic presence.

3. He didn’t have a high opinion of Harvard

Henry Adams described his life as “a search for education the schools cannot give.” In his autobiography, he mentioned attending Harvard simply because it was a family tradition. However, he admitted that ‘had ever done any good there, or thought himself the better for it.’

He also wrote the college offered “chiefly advantages vulgarly called social, rather than mental.”

“Any other education would have required a serious effort, but no one took Harvard College seriously,” he wrote.

Despite his critical view of Harvard, Adams received an unexpected opportunity at age 32. Harvard President Charles W. Eliot invited him to teach medieval history – a subject Adams admitted he was “utterly and grossly ignorant” about. Embracing the challenge, he took the job and for six years, he taught a comprehensive course on European history spanning from the 10th to the 16th century.

4. He secretly wrote a best selling novel

In 1880, Henry Adams published a book called “Democracy: An American Novel.” The book quickly became a best-seller, sparking curiosity about the author’s identity and the real-life inspirations behind the characters.

Speculation ran wild. Some believed Adams’ friends, John Hay and Clarence King, might have written it. Others thought it could have been his wife, Clover Adams. It wasn’t until after Adams’ death in 1918 that his publishing company confirmed he was the author.

“Democracy” tells the story of Madeleine Lee, a savvy New Yorker who moves to Washington, D.C., and starts a salon that attracts powerful men. Two of these men fall in love with her and scheme against each other, all while the Bulgarian minister observes their antics.

More than a century later, in 2005, a Washington Post writer gave the novel a glowing review, calling it a “worldly, profoundly knowing, deliciously elitist social comedy.” This review coincided with the Washington National Opera’s performance of an opera based on Adams’ novel.

5. He believed Ulysses S. Grant ruined his life

In 1868, Henry Adams relocated to Washington, D.C., after working as his father’s secretary. He also served as a foreign correspondent for the New York Times and the Boston Advertiser, and contributed to the North American Review.

Eager to make a name for himself in the political scene, Adams envisioned a future where he could influence national affairs as a political journalist. Brimming with ambition and confidence, he even hoped that Ulysses S. Grant, upon winning the presidency in 1868, might consider him for an advisory role. His high hopes were not unfounded, as many of his family friends already held significant positions in government.

Henry Adams struggled to make the right connections in Washington, D.C., often rubbing people the wrong way. After attending a White House dinner in 1870, he wrote with misplaced confidence, “I chattered with that blandness for which I am so justly distinguished,” he wrote, “and I flatter myself it was I who showed them how they ought to behave.” Well, not really.

However, President Grant had little regard for the Adams family. He refused to appoint their friends to his Cabinet and dismissed others, famously telling his secretary that the Adamses “did not possess one noble trait of character.”

Henry Adams then wrote, “My family is buried politically beyond recovery for years. I am becoming more and more isolated as far as allies go.” When Grant passed away, Adams’s bitterness was evident in his harsh epitaph: “He had no right to exist.”

6. He had a keen interest in science and technology

Henry Adams’s interest in science and technology is most prominently reflected in his autobiographical work, “The Education of Henry Adams,” where he contrasts the dynamo, a symbol of industrial power, with the Virgin Mary, representing spiritual power.

This comparison highlights his contemplation of the profound changes technology was bringing to human life and values. He saw the dynamo as a representation of the modern era’s technological energy and the profound shift from religious to technological worship.

7. He had an unrequited love affair for 35 years

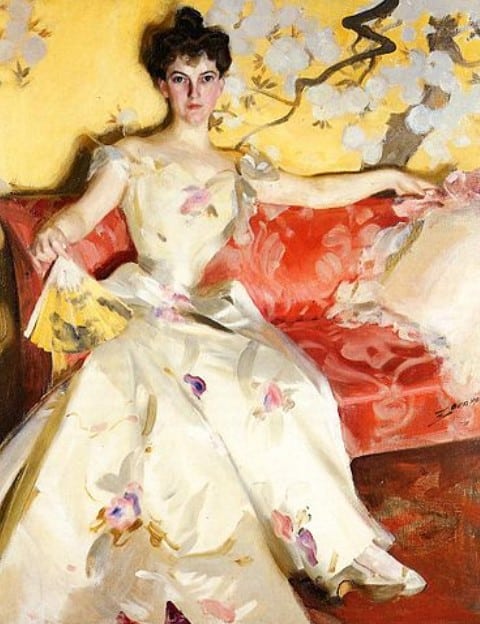

Henry Adams met Elizabeth Sherman Cameron in 1881, nearly five years before his wife Clover’s tragic suicide. Lizzie, as she was known, was a captivating hostess who loved to read but was trapped in an unhappy marriage to a wealthy, alcoholic U.S. senator. For 35 years, she kept Adams enthralled, even while flirting with Russian Prince Orloff, poet Joseph Trumbull Stickney, and famous sculptors Saint-Gaudens and Rodin, as well as John Hay.

Though their 35-year correspondence was mostly Platonic, it sparked plenty of gossip among their social circles. The true nature of their relationship remained a mystery, with many wondering if it ever became romantic.

When Henry Adams had a stroke in 1912, Lizzie wanted to care for him, but his sister Mary objected. “I won’t have her,” Mary declared, worried about the potential scandal and the talk that would follow if Lizzie came from Paris to take charge of her brother’s care.