Unveiling Colonial Classrooms: What Was School Really Like?

Have you ever wondered how colonial schoolrooms compare to today’s classrooms? The contrast is striking!

Back in colonial times, education was a mixed bag—ranging from formal schools to home instruction, often steeped in religious teachings. Quality and access varied greatly.

Today, however, we benefit from standardized curricula and universal access to education. Dive in with us as we uncover what schooling was truly like in the colonial era.

Puritan settlers in New England prioritized literacy

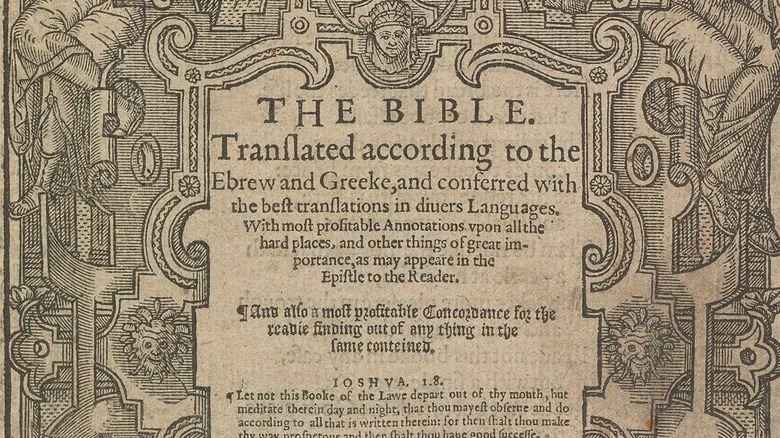

In early New England, European settlers were driven by a deep belief that literacy was a sacred duty.

For the Puritans, reading the Bible was a personal connection to God, and they viewed illiteracy as a serious religious failing. They built schools rapidly to ensure everyone could read the Scriptures for themselves.

Massachusetts took a significant step in 1642 with the Massachusetts Compulsory Attendance Law that mandated basic education for children. However, this law required families to teach children at home, which often led to inconsistent enforcement.

The 1647 Old Deluder Satan Act followed, stipulating that towns with over 50 households must establish schools and hire teachers. Larger towns were required to build grammar schools to prepare students for college.

For Puritans, education was more than a civic duty—it was a religious necessity. As Edward Janak notes, “Literacy took on a religious element,” demonstrating how crucial reading was to the early settlers.

How did kids learn inside a New England schoolhouse?

In colonial Massachusetts, each town decided on the number of schools, their funding, and the fees students had to pay.

According to Edward Janak, “In the colonial era, all schools were ‘public’ in the sense that anyone who could afford it could go.” Typically, children were expected to attend a school within a mile or two of their home.

At a petty school, tuition was modest—6 pence per week for reading and another 6 pence for arithmetic, as noted in Clifton Johnson’s 1904 book, Old-Time Schools and School Books.

In more rural areas, families often paid with farm produce like barley or corn. Students also had to supply firewood in winter or face a fine of 4 shillings.

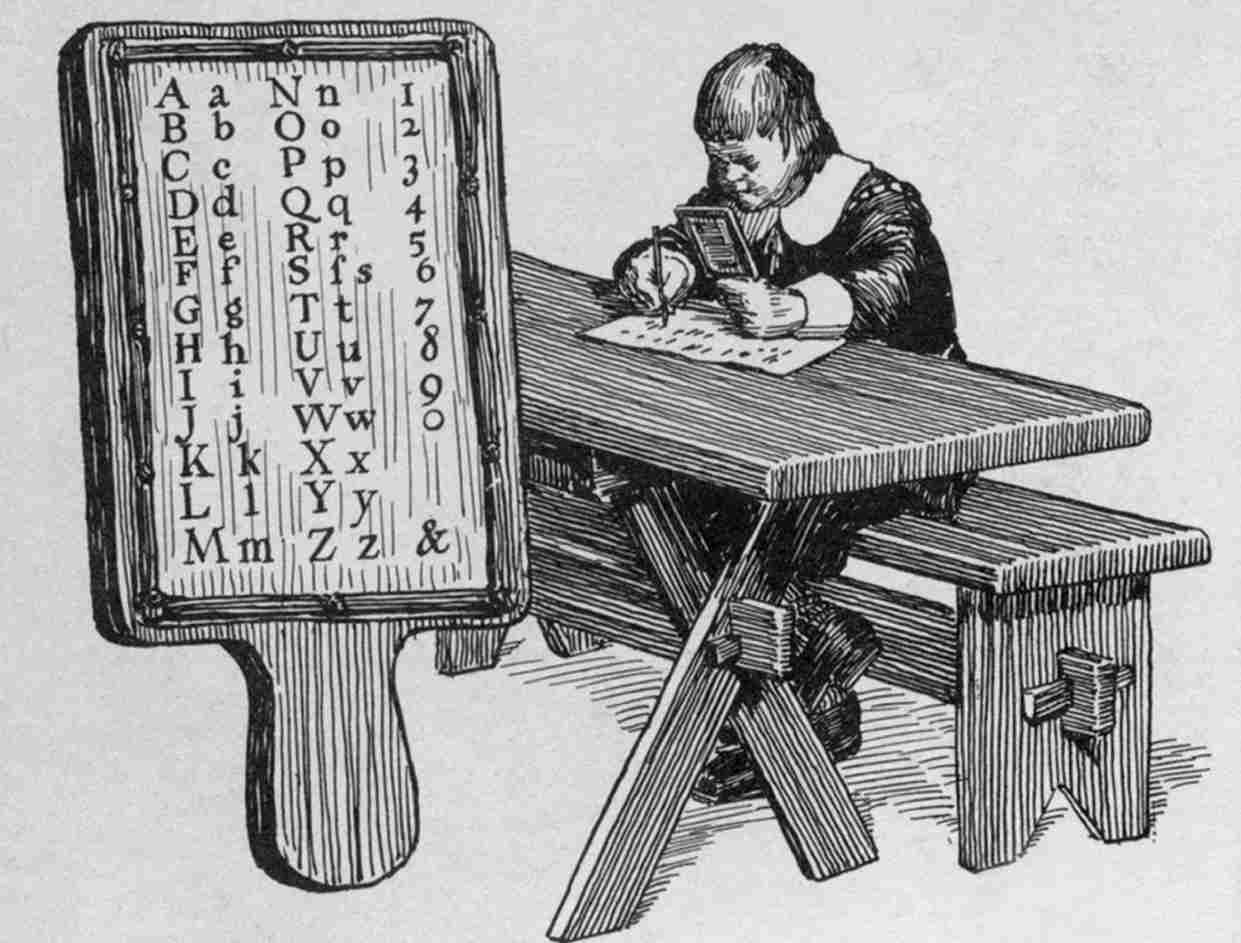

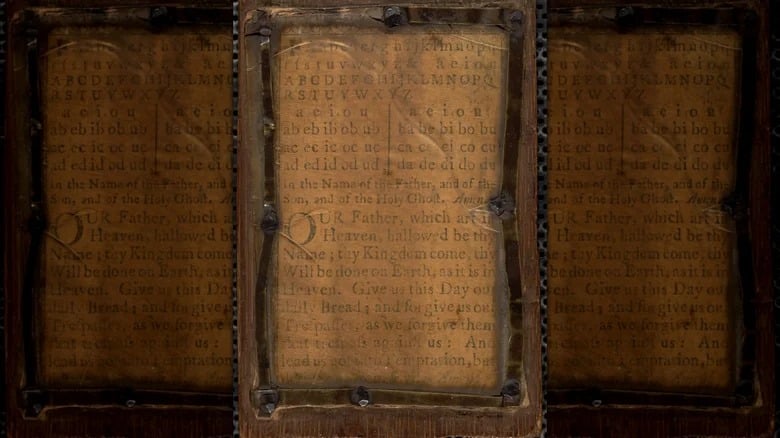

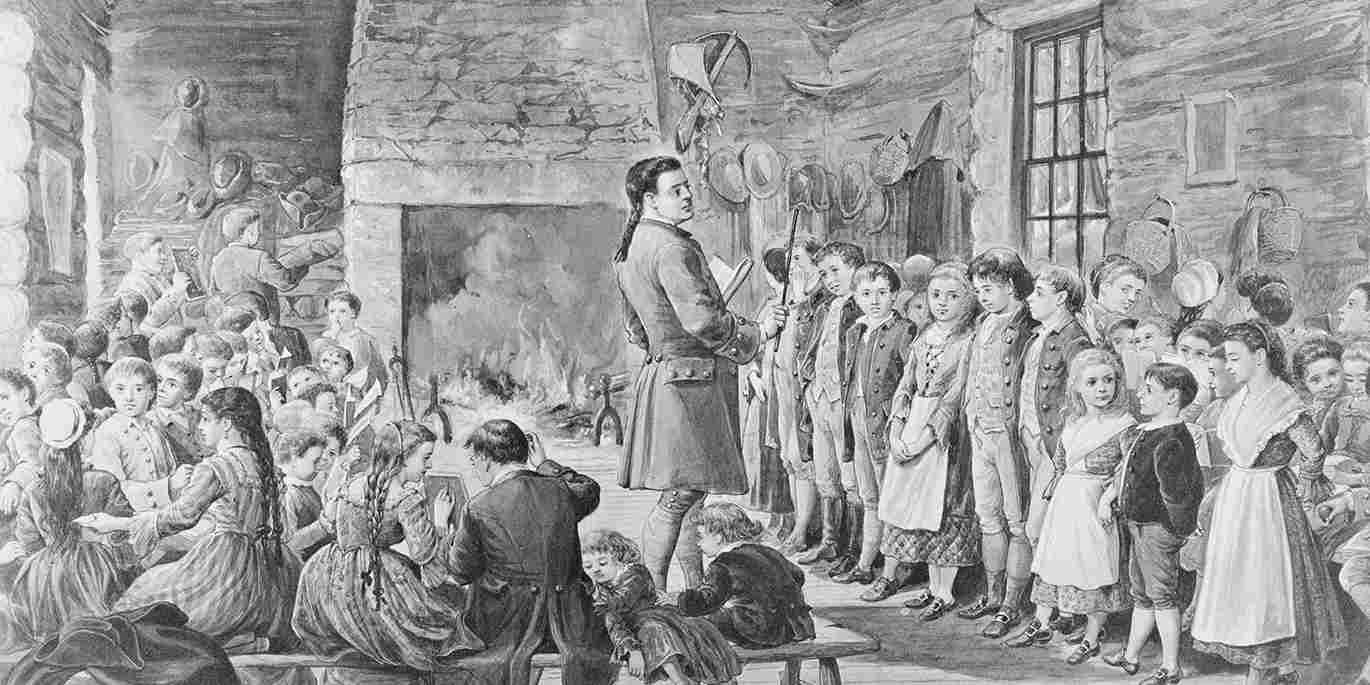

Petty schools were often one-room buildings where children of different ages learned together. Attendance was irregular due to farming and other duties, so children might come and go based on their family’s needs.

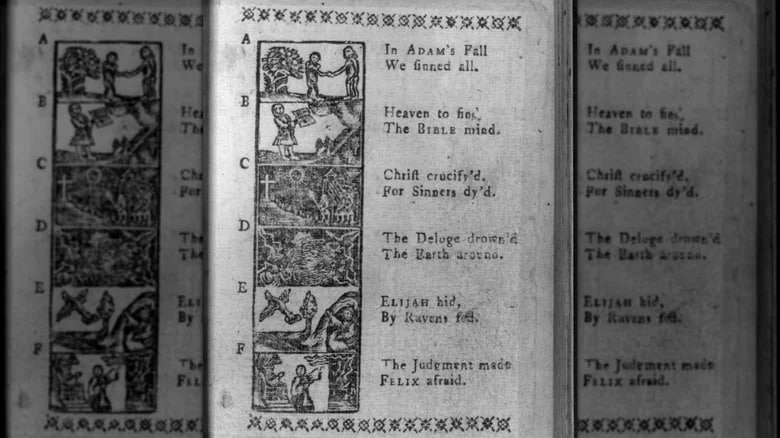

The curriculum included reading, writing, spelling, grammar, and arithmetic, all laced with religious teachings. “The New England Primer,” a popular textbook, featured Puritan rhymes like “In Adam’s fall, we sinned all” and was used for memorization and recitation.

Writing tools were simple: goose quills and homemade ink. Schoolmasters spent a lot of time preparing and mending quills. Students had to bring their own ink made from dissolving powder or boiling swamp maple bark.

Younger children, aged five to seven, might attend a “dame school,” an informal setup run by a local woman who taught basic skills for a small fee.

Grammar schools, on the other hand, were typically reserved for wealthy boys who needed to master Latin and Greek for entry into prestigious colleges like Harvard, founded in 1636.

What were schools like in the Middle Colonies and the South?

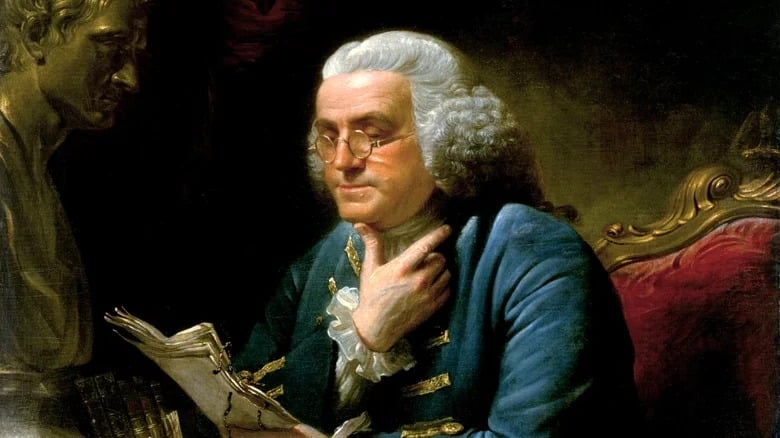

While Puritans in New England were focused on integrating religion into education, other intellectual movements were gaining ground in the American colonies.

“Instead of just moralizing at students, an Enlightenment-inspired curriculum included science education, reasoning, and advanced mathematics,” says Edward Janak.

These were more common among colonial elites. “Instead of just moralizing at students, an Enlightenment-inspired curriculum included science education, reasoning, and advanced mathematics,” says Edward Janak.

The Middle Colonies, including New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, were more receptive to Enlightenment ideas. Students at these schools engaged with philosophy and other intellectual pursuits.

This progressive educational model influenced prominent figures like Benjamin Franklin, who, despite dropping out of Boston Latin School at a young age, was exposed to these advanced ideas.

In contrast, the Southern colonies faced different challenges. The vast distances between farms and plantations made regular schooling difficult. The wealthy often hired private tutors or sent their children to study in England or Europe.

In some communities, residents collaborated to create “field schools”—temporary schools set up in fallow fields and moved from plantation to plantation.

“When it came time to plant the field, they would ‘put the schoolhouse on log and roll it from one plantation to the other,’” notes Janak.

Outside of New England, education was less regulated by colonial governments and more dependent on local efforts.

As Governor William Berkeley of Virginia observed in 1671, education in the colonies followed “the same course that is taken in England out of towns,” where families were largely responsible for instructing their children according to their means.

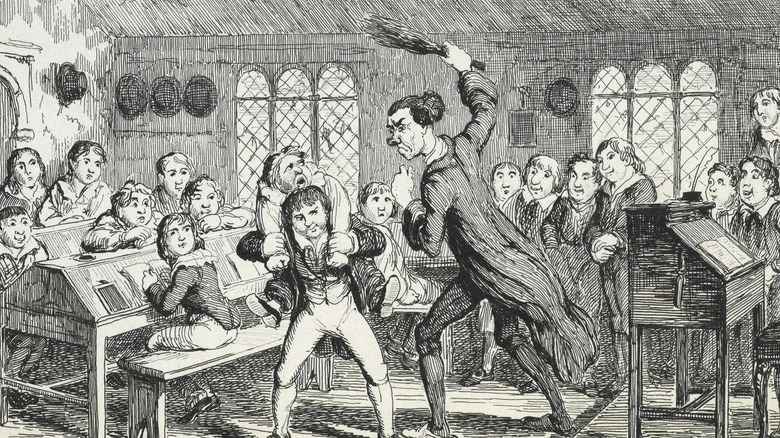

Colonial teachers, lacking formal training, used severe corporal punishment

In the colonial era, finding qualified teachers was a challenge. Without formal training or professional education, anyone who claimed to be a “schoolmaster” could take on the role.

“Teaching was very much a commercial endeavor,” notes historian Edward Janak. “Whoever hung up a shingle as a ‘schoolmaster’ got to do it.”

Most teachers were men, and many traveled from town to town, offering their expertise in subjects like arithmetic or penmanship.

In Virginia and the Southern colonies, some teachers were debtors or petty criminals, sometimes even sold into teaching as indentured servants.

“Not infrequently they were coarse and degraded, and they did not always stay their time out,” writes Clifton Johnson, noting an advertisement for a schoolmaster who was “much given to drinking and gambling.”

George Washington’s first teacher was a bondsman named Hobby, who also worked as a church sexton.

Corporal punishment was standard practice in colonial schools. In Puritan New England, it was considered divinely sanctioned. A 1645 Massachusetts rule read, “The rod of correction is a rule of God necessary sometimes to be used on children.”

Tools like the ferule, a long flat ruler, were commonly used, but more severe methods like caging or cooping were also employed. Even dame schools, run by older women, saw their share of discipline, with tactics ranging from a sharp thimble tap to dunce caps.