The Story of Margot Frank, Anne Frank’s Forgettable Sister And Her Secret Diary

Margot Frank is best known as “the sister of Anne,” often overshadowed by her more famous sibling.

The image we have of her mainly comes from Anne’s critical view in her diary. How did others see Margot, and what is revealed about her life?

You might not know she also kept her own diary. However, while Anne’s diary was preserved and published after their deaths in 1945, Margot’s diary was lost. Despite this, some insights into Margot Frank were revealed.

Margot Frank was a diligent and academically brilliant student

Margot Frank was born on February 16, 1926, in Frankfurt, Germany, as the first child of Otto and Edith Frank. From a young age, she was noted for being “neat and careful,” qualities that earned her high praise in her first school report, describing her as “very diligent!”

This meticulous nature would follow her throughout her life and set her apart as a model student and a dedicated individual.

In 1929, her younger sister, Anne Frank, was born. The two sisters had distinct personalities; Anne often described herself as the “mischief maker,” while Margot was the “brainy” and “brilliant” one.

The family’s peaceful life was disrupted in the 1930s when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party rose to power. Concerned about the growing anti-Semitic sentiments and the deteriorating economic conditions in Germany, the Franks decided to move to Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

Despite the challenges of adjusting to a new country and learning a new language, Margot quickly excelled in her Dutch school. By the end of her primary education, she had significantly improved her grades.

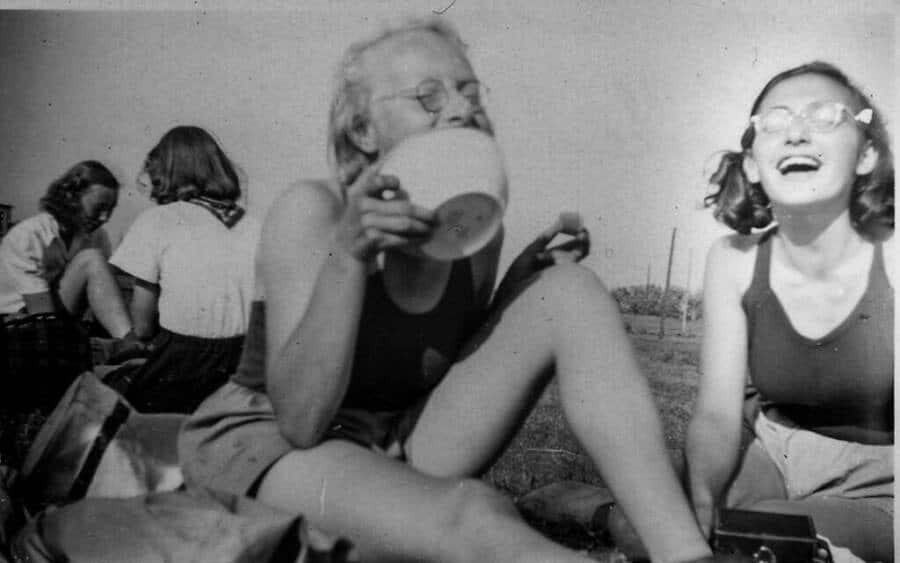

Margot’s academic prowess was not limited to the classroom; she also made friends and engaged in extracurricular activities like rowing and playing tennis.

However, the looming threat of Nazi Germany was ever-present. In a poignant letter to her American pen pal, dated April 27, 1940, Margot wrote, “We often listen to the radio, for these are stressful times. We never feel safe, because we border directly on Germany and we are only a small country.”

Her fears were justified when, on May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. This invasion drastically changed Margot Frank’s life, as the Nazis imposed severe restrictions on Jewish families. After the summer of 1941, Margot had to leave the Lyceum for Girls and transfer to the Jewish Lyceum.

Hetty Last, a former classmate, recalled seeing Margot waiting by the Lyceum for Girls as she missed her old school and friends. The Nazis’ antisemitic policies also forced Margot to quit tennis and rowing.

Despite that, Margot excelled academically. Anne noted in her famous diary, “Brilliant as usual. She would move up cum laude if that existed at school; she is so brainy!”

The Frank family went into hiding

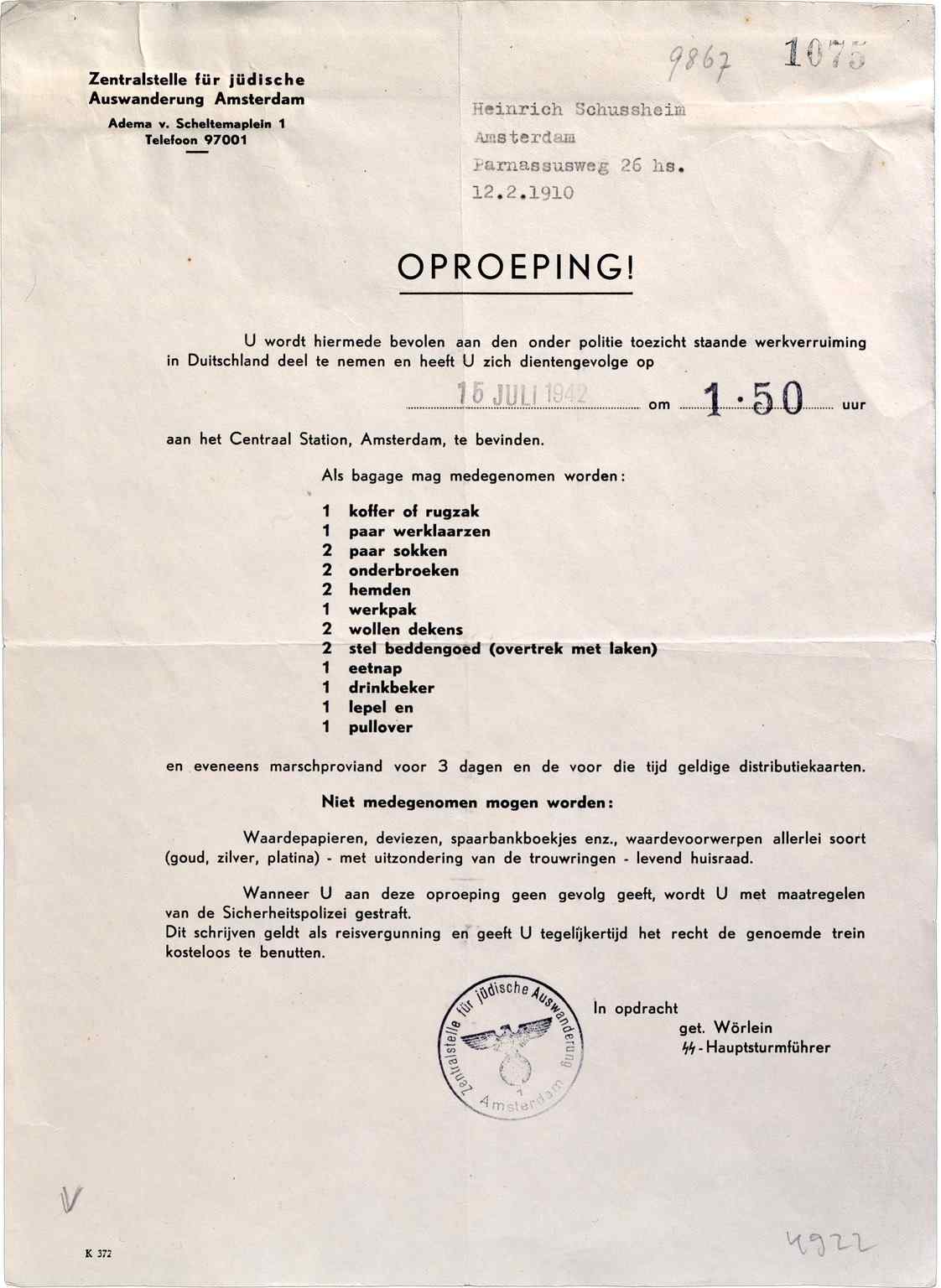

On July 3, 1942, Margot received her stellar report card from the Jewish Lyceum, but just two days later, she was called up for a labor camp. Her parents, fearing for her safety, decided to go into hiding the next day.

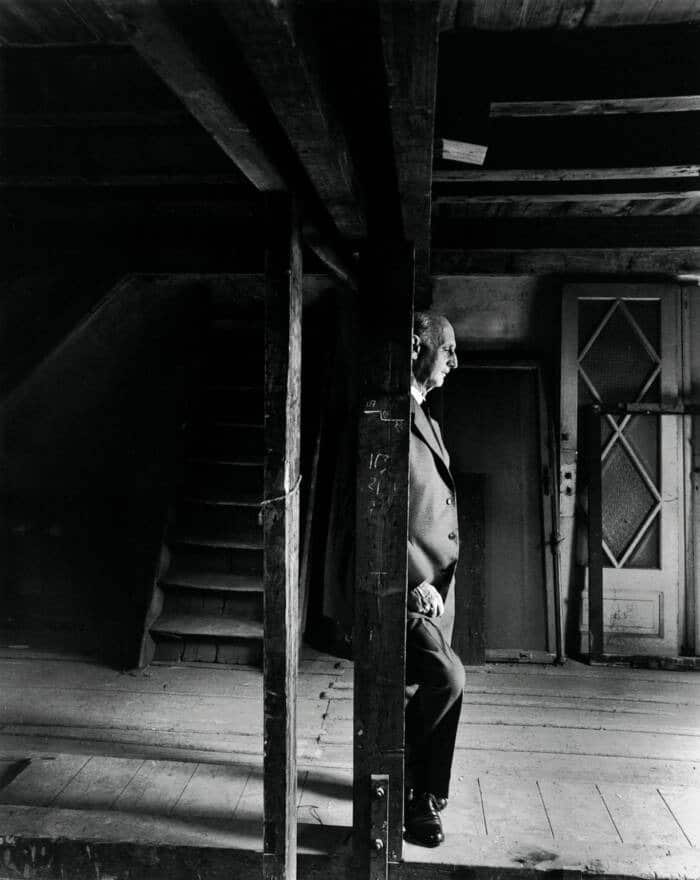

From July 1942 onwards, Margot, together with her parents and Anne, hid in a secret annex behind Otto’s office at Prinsengracht 263. She initially shared a room with her sister, but when Fritz Pfeffer joined them, Margot moved to her parents’ room.

Despite the cramped conditions, Margot continued her studies diligently. Anne made an impressive list of what Margot was studying:

“English, French, Latin by correspondence… Geometry, Physics, Chemistry… reads everything, preferably on religion and medicine.”

She described Margot as “weak-willed and passive” in one entry, while in another, she noted their father’s preference for Margot, calling her “the cleverest, the kindest, the prettiest, and the best.”

Margot’s solitude became more apparent when Anne developed feelings for Peter van Pels. Anne wondered if Margot also had feelings for Peter, but Margot denied it.

In a note to Anne, Margot expressed her loneliness, writing, “I only feel a bit sorry that I haven’t found anyone yet, and am not likely for the time being, with whom I can discuss thoughts and feelings.”

Over time, Anne’s feelings toward Margot softened. By early 1944, she wrote, “Margot’s much nicer. She’s not nearly as catty these days and is becoming a real friend. She no longer thinks of me as a little baby who doesn’t count.”

Sadly, the sisters never had a chance to deepen their relationship further. On Aug. 4, 1944, the Frank family and the others in the annex were arrested after someone betrayed them.

Before arriving at Bergen-Belsen, the Frank family had been sent to Camp Westerbork and then Auschwitz-Birkenau. There, Otto was separated from Edith, Margot, and Anne.

Margot’s future plans and dreams were abruptly ended by the horrors of the concentration camps. According to Victor Kugler, who witnessed the arrest, “Margot was weeping silently.”

Margot Frank tragically died in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp

In November, Margot and Anne were further separated from their mother and sent to Bergen-Belsen.

Life in the camp was described by Nanette Konig, a former classmate of Anne’s, as a “hell where people were not exterminated immediately but died from hunger, dysentery, typhus, cold, exhaustion, beatings, torture, and exposure.”

Margot and Anne contracted spotted typhus. Rachel van Amerongen-Frankfoorder, a fellow prisoner, later recalled, “They had those hollowed-out faces, skin and bone. You could really see both of them dying, as well as others.”

Tragically, both sisters succumbed to the disease just two months before British soldiers liberated the camp.

Margot and Anne’s exact dates of death remain unknown, but a friend recounted in a 2015 report by the Anne Frank House that by February 1945, the two Frank girls “simply weren’t there anymore.”

Margot was 18 or 19, and Anne was 15. They were among the 35,000 people who died at Bergen-Belsen between January and April 1945 from illness, starvation, and exhaustion.

What happened to Margot Frank’s diary?

At the end of the war, Otto Frank returned to the Netherlands, the only member of the Frank family to survive. Soon after, he reconnected with his former secretary, Miep Gies, who had helped hide the family during the war.

Gies had saved Anne’s diary from the annex after the Franks were deported, hoping to one day return it to Anne. Instead, she gave it to Otto.

Otto decided to publish the diary, which became one of the most famous accounts of the Holocaust, translated into more than 70 languages.

Anne’s diary reveals that Margot also kept a diary during their time in hiding. Anne wrote, “Margot and I got in the same bed last evening, it was a frightful squash, but that was just the fun of it, she asked if she could read my diary sometime, I said yes at least bits of it, and then I asked if I could read hers.” Unfortunately, Margot’s diary did not survive.

Margot Frank’s story remains largely untold. Her best friend, Jetteke Frijda, expressed her disappointment to Otto, saying, “I think it’s wonderful what you are doing for Anne, but I think it’s a pity that nothing is mentioned anymore about Margot. She is also worthy of being mentioned.”

However, Frijda also believed that Margot, being less extroverted than Anne, “would not have wanted her private thoughts exposed to the world.”