The Remarkable Journey Of Tenley Albright From Ice Rinks To Operating Rooms

History is rich with inspiring stories about remarkable women, and one of the most captivating is that of Tenley Albright.

She became the first U.S. woman to win an Olympic gold medal in figure skating. What many – might not know is that at 11, Tenley was stricken with a disease that threatened to end her skating career before it even began.

She overcame all odds, and her story doesn’t end on the ice. Keep scrolling to discover how this extraordinary woman skated her way to Olympic victory and later transitioned into a respected and influential surgeon.

Conquering polio as a young girl

Tenley Albright was born in Newton in July 1935, the daughter of a prominent Boston surgeon. At eight, she received her first pair of skates, and her parents even flooded a portion of their backyard to create a rink for Tenley and her brother.

As her passion for skating blossomed, she began training at the Skating Club of Boston.

There, her instructors quickly noticed her exceptional talent despite her prioritizing academics over the sport. By nine, she was flawlessly cutting figure eight into the ice, and at eleven, she won the U.S. Eastern Junior Championship.

Sadly, that same year, Tenley Albright contracted polio, a disease that made many children partially paralyzed or confined to iron lungs. After several weeks in the hospital, she was fortunate enough to escape paralysis but was left weak and withered.

Doctors suggested that skating could aid in her recovery, and with unwavering determination, she returned to the rink to rebuild her strength.

For Tenley, the rehabilitation process was far from a chore—it was exhilarating. She focused on regaining her muscle strength through skating, turning each session into a celebration of progress. She later recalled her return to the ice:

“It seemed so huge after being in the hospital so long… hanging on to the barrier, sort of creeping along it, and staying down at one end. But when I found that my muscles could do some things, it made me appreciate them more.

I’ve often wondered if maybe the reason it appealed to me so much was that I had a chance to appreciate my muscles, knowing what it was like when I couldn’t use them.”

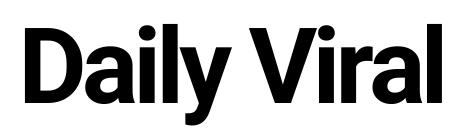

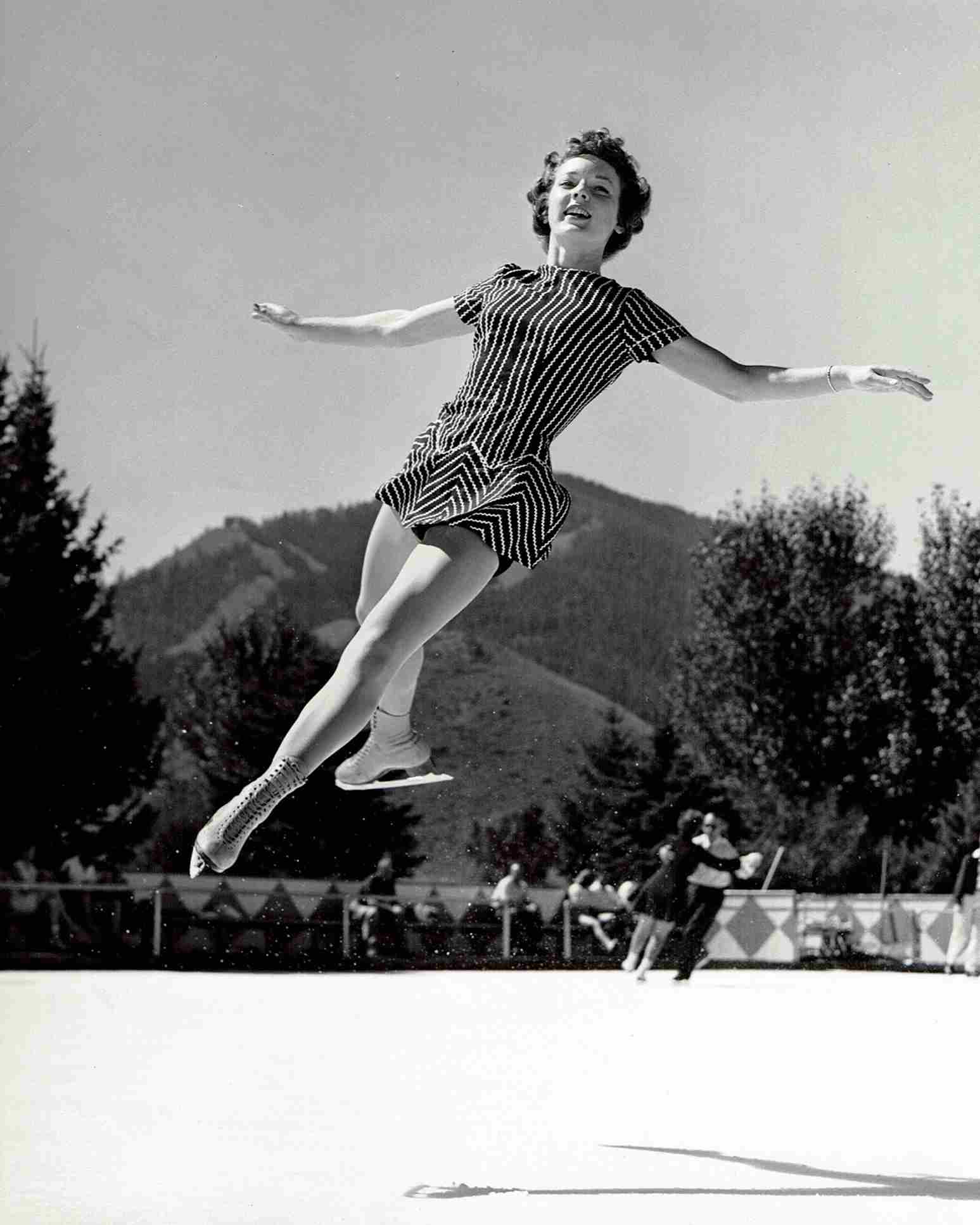

Shining as a star on ice

As Tenley Albright focused on skating her way back to health, she began to take risks on the ice and overcame her fear of falling. She once said, “If you don’t fall down, you aren’t trying hard enough, you aren’t trying to do things that are hard enough for you.”

“I can remember taking several pairs of skating tights to the rink because I would get so soaked, falling down again and again and again while I tried the sit-spin. . . .

[But] the feeling when you finally do manage not to fall down, when you are trying something new, is such a wonderful feeling that you want that feeling again. . . . And that applies to whatever you do.” she recalled.

Incredibly, just four months after returning to the ice, Tenley won the Eastern Juvenile Skating Competition.

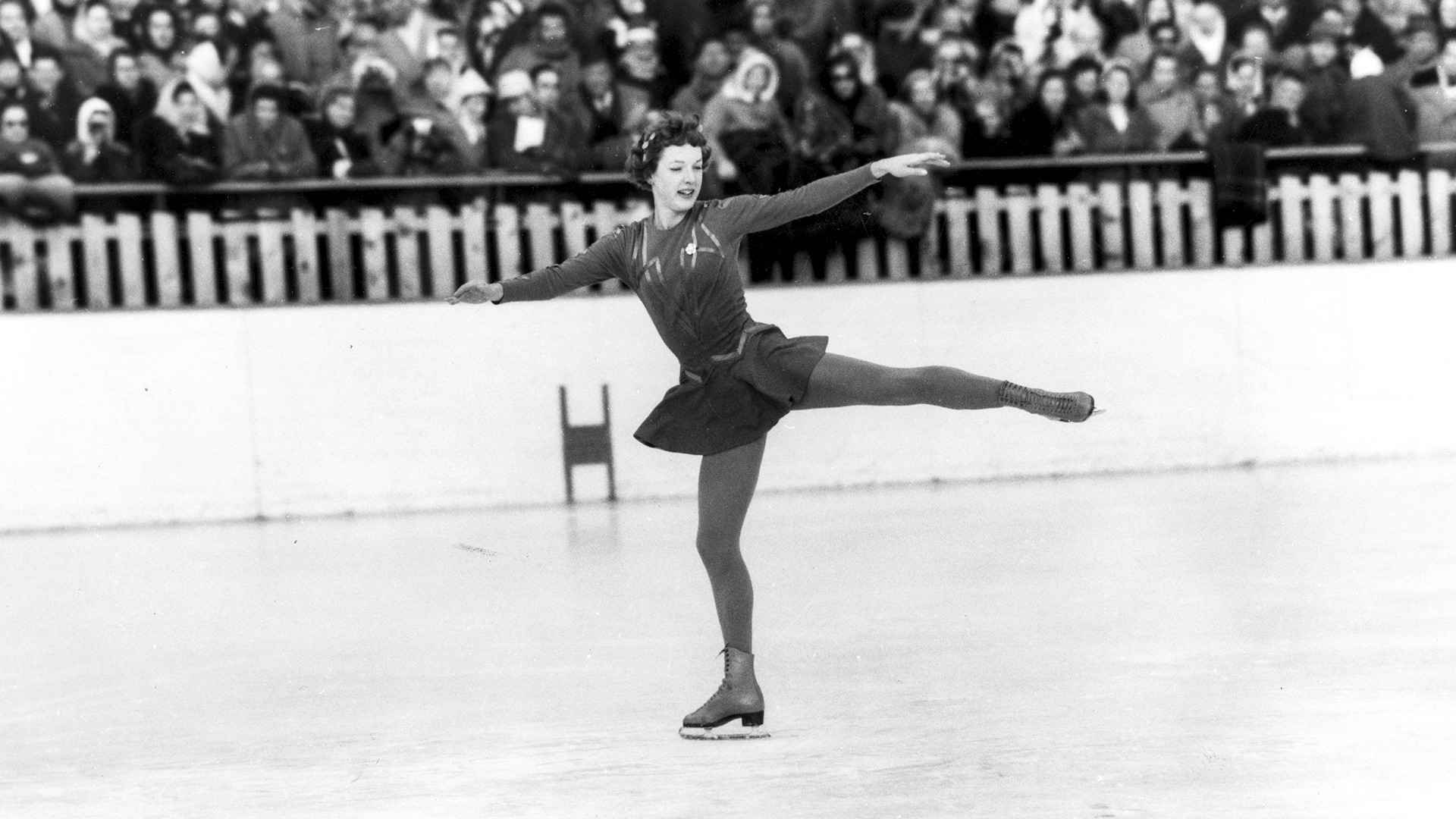

Her success continued with victories at the U.S. Ladies Novice championship and the U.S. Ladies Junior title by age 14. She qualified for the U.S. Olympic team in 1952 and brought home a Silver Medal.

She balanced a rigorous schedule by waking up at 4:00 am to skate before school and returning to the rink in the afternoon. This led her to skate for seven hours each day while maintaining her studies, eventually gaining admission to Radcliffe College as a pre-med student.

Even at Radcliffe, Tenley continued to balance her rigorous academic schedule with her demanding training routine.

She won five consecutive national championships and, in 1953, became the first woman skater to win the sport’s “triple crown,” capturing the World, North American, and United States figure skating titles.

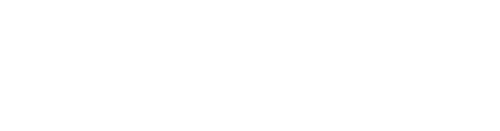

In 1956, at 20 years old, she took a leave from college to prepare for the Olympics. Two weeks before the 1956 Winter Olympics, disaster struck.

Tenley fell on the ice, and the blade of her left skate cut her right ankle, slashing a vein and scraping to the bone. Her surgeon father flew to Italy to treat the injury. She was bedridden and barely able to walk.

Despite that, she decided to stay in the competition, stating, “The one thing I want to be able to do after it’s over is say that was my best.”

Tenley’s best was indeed remarkable. Skating before 10,000 spectators at the 1956 Winter Olympics in Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy, she won the Gold Medal, becoming the first American female skater to achieve this feat. She was welcomed back to Boston with a parade.

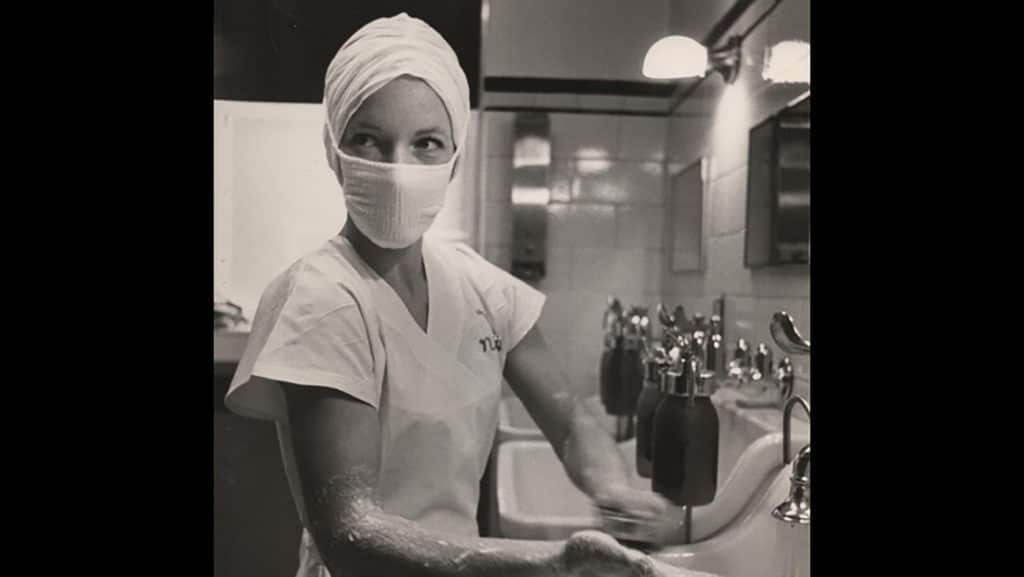

An inspiring journey in medicine

Tenley Albright made a bold decision to retire from competitive skating after winning her Olympic Gold Medal. Rather than pursuing lucrative professional contracts, she chose to focus on her dream of becoming a surgeon.

To catch up with her classmates, she took summer classes and graduated from Radcliffe in just three years. By the fall of 1957, she was ready to start a new chapter at Harvard Medical School.

Tenley approached medical school with the same discipline and dedication she had developed as an athlete, taking one step at a time.

After graduating from Harvard Medical School in 1961, she practiced surgery for 23 years and continued as a faculty member and lecturer at Harvard.

She also played a significant role as the chief physician for the US Winter Olympic team in 1976 and chaired the Board of Regents of the National Library of Medicine.

Her medical career flourished alongside her personal life. Tenley became a respected surgeon and blood plasma researcher, all while raising three daughters with her husband in Brookline. She could often be seen skating around the pond at the nearby Country Club.

Her exceptional contributions to both the medical and sports fields were recognized with her induction into the International Women’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1983. In 2000, Sports Illustrated named her one of the “100 Greatest Female Athletes.”