The Orphan Trains: America’s Forgotten Journey Of Hope And Hardship

In the mid-19th century, as poverty and homelessness overwhelmed America’s bustling cities, a bold yet controversial experiment began.

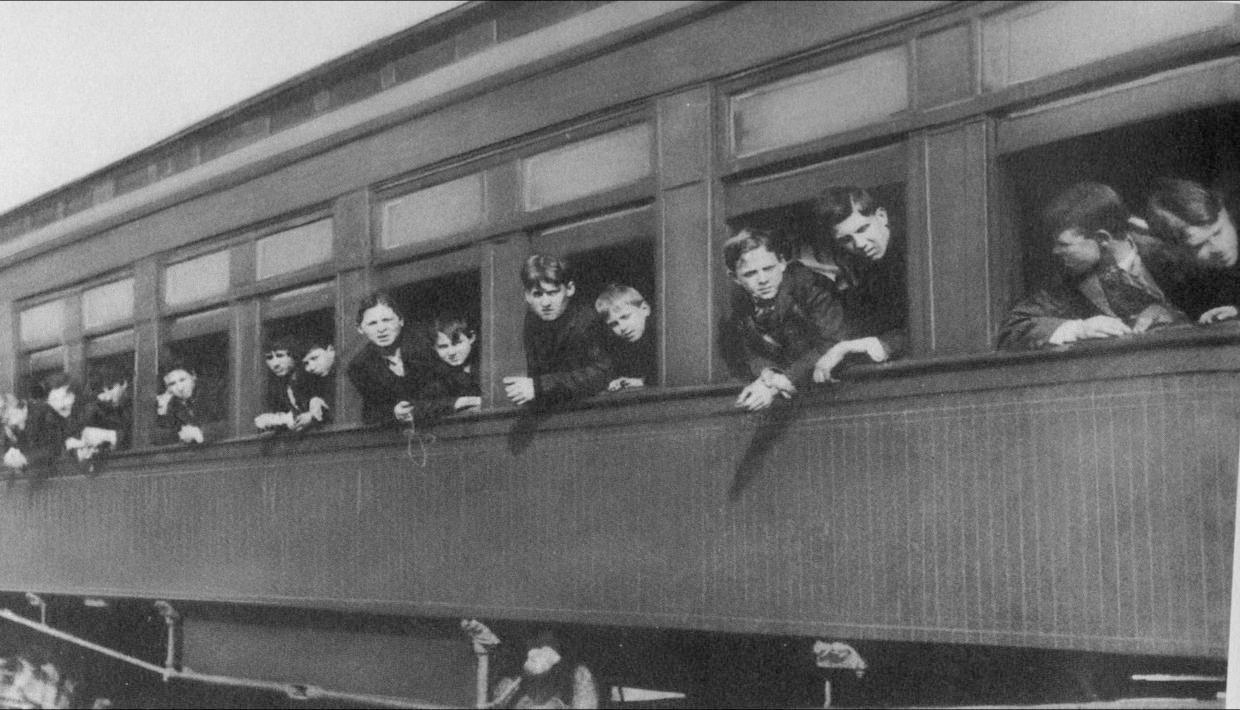

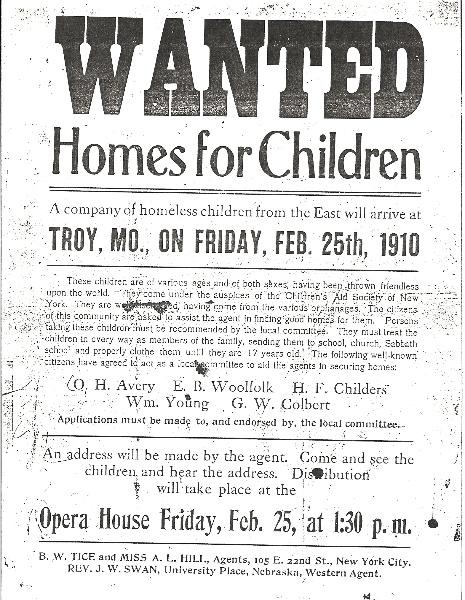

Between 1854 and 1929, over 200,000 children were uprooted from overcrowded urban centers and sent on trains across the United States to find new families and opportunities.

This ambitious social movement, known as the Orphan Train Movement, was meant to offer hope and a second chance for many, yet it revealed the complexities of relocation, adoption, and societal expectations.

The origins of the Orphan Train Movement

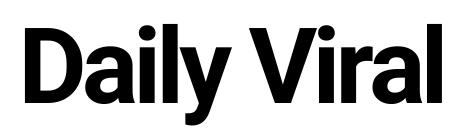

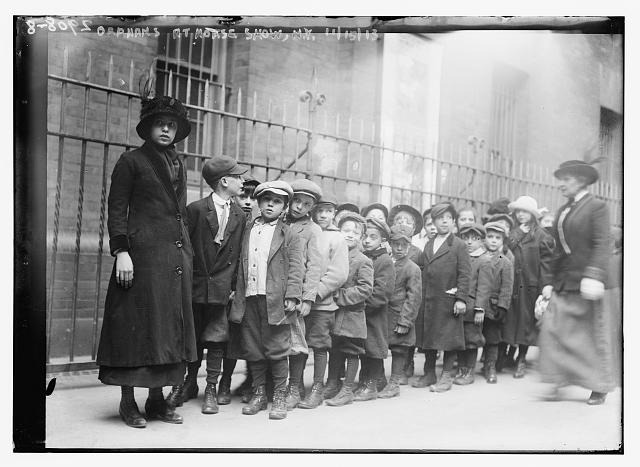

By the mid-1800s, the streets of cities like New York and Boston teemed with orphaned and homeless children.

These children, often referred to as “street Arabs,” survived through begging, selling small goods, or engaging in petty crimes.

With growing immigrant populations, the number of destitute children soared, leaving local authorities unable to cope.

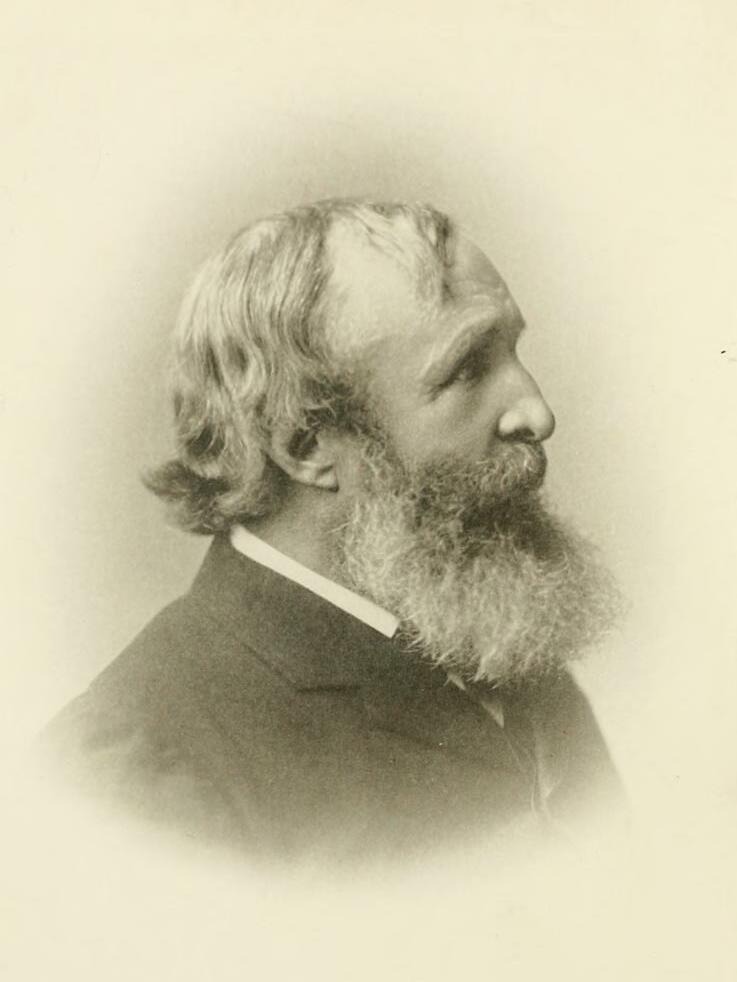

It was Charles Loring Brace, a visionary minister from Connecticut, who first saw a solution to this growing crisis. In 1853, he founded the Children’s Aid Society with a mission to rescue these children from the harsh realities of urban life.

Rather than placing them in overcrowded, grim orphanages Brace proposed an innovative idea: send the children westward to rural families who could offer them homes and employment.

“The best of all asylums for the outcast child is the farmer’s home,” Brace famously said. His idea laid the foundation for the largest child relocation program in American history.

Life on the Orphan Trains

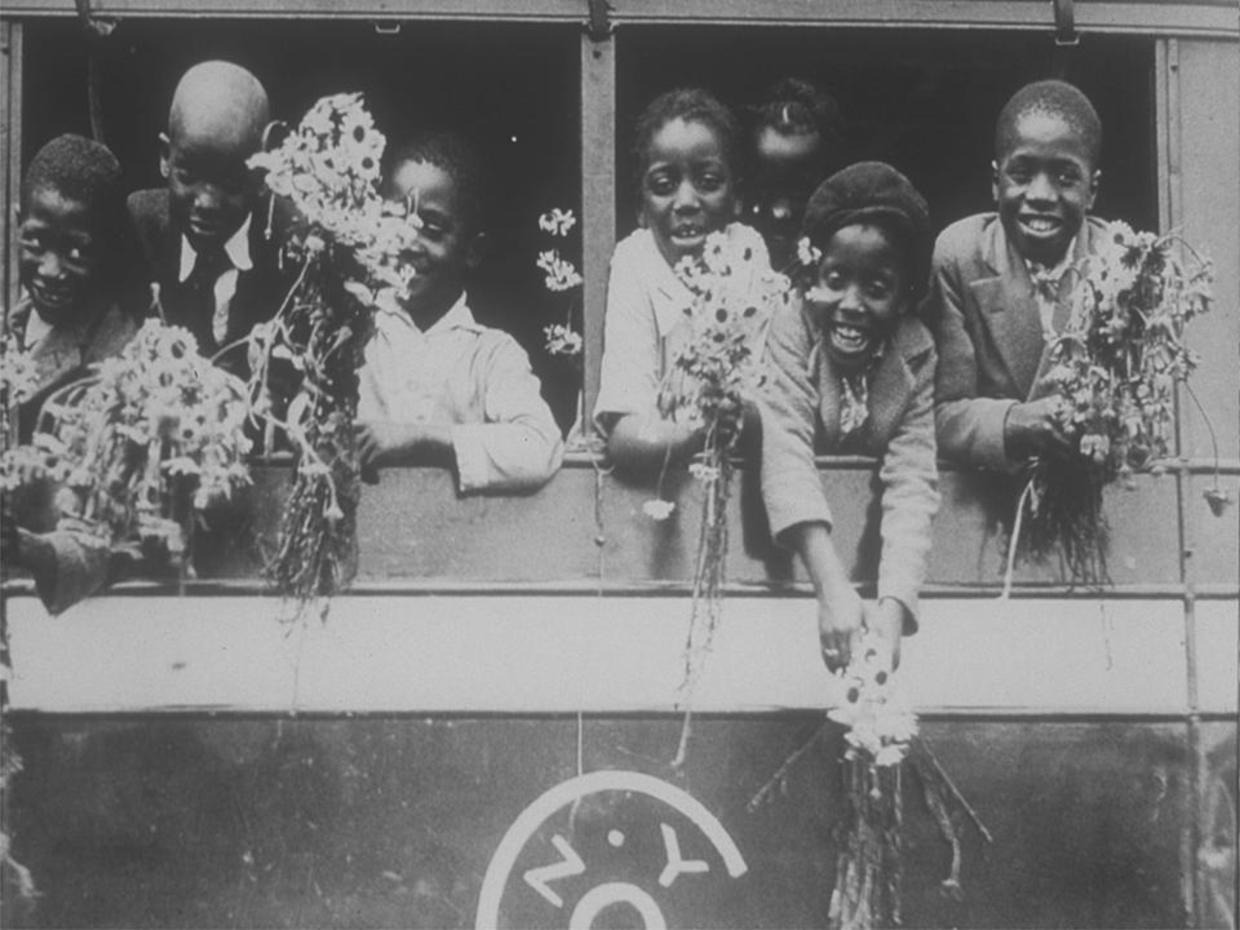

For many children, the journey on the orphan trains was both thrilling and frightening. Most had no idea where they were going or what awaited them at the end of the line.

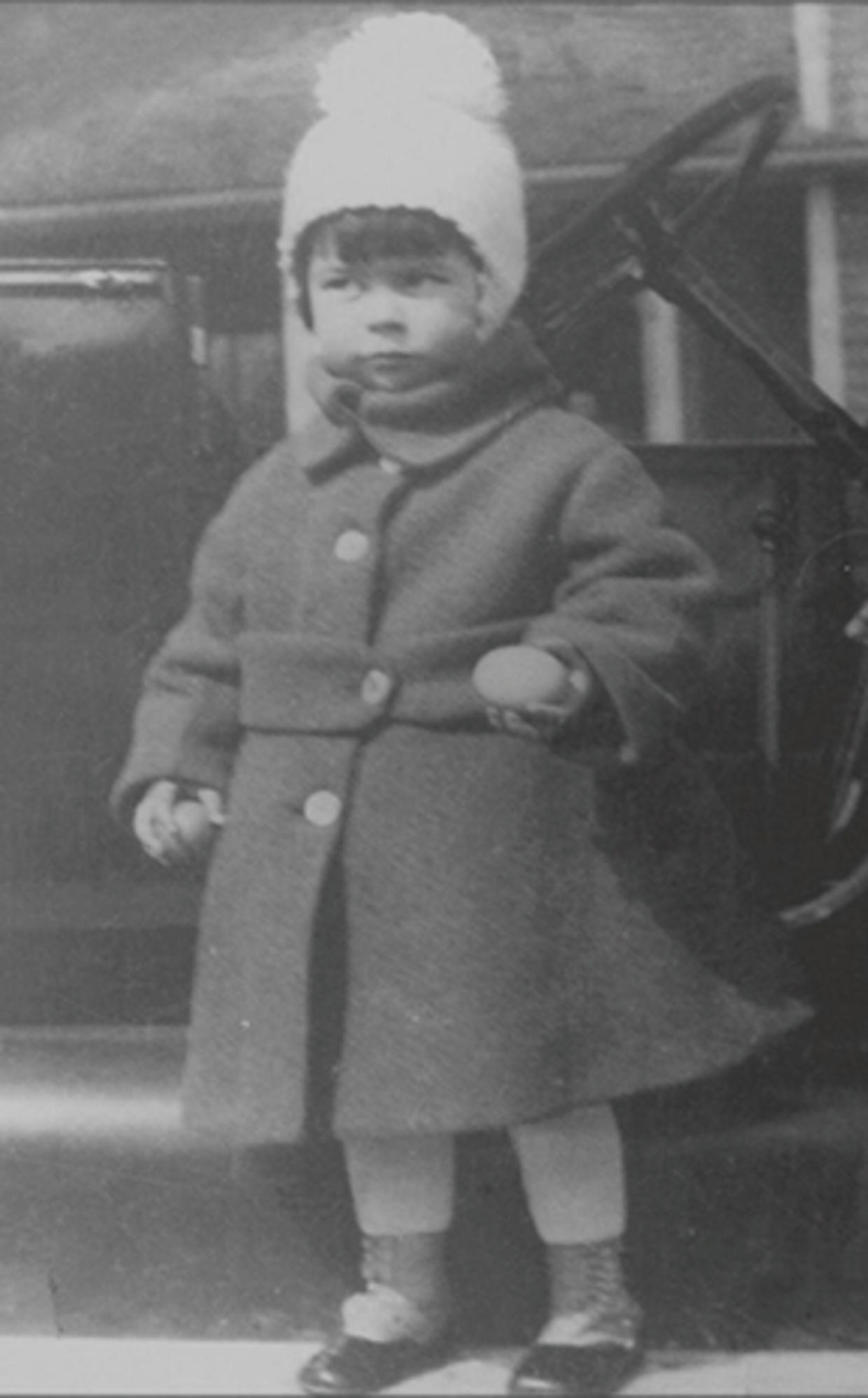

Some were given new clothes, a cardboard suitcase, and a name tag before being placed in the care of chaperones who accompanied them on their westward journey.

Elliot Bobo was just eight years old when he boarded an orphan train. His mother had died when he was two, and his father struggled with alcoholism.

As Elliot remembered, “Far as I know, my father hit the bottle pretty heavy, and they took us away from him.”

The Children’s Aid Society gave him a small suitcase, which he still keeps to this day. “I had all my possessions in there, which wasn’t much. No shoes, just a change of clothes,” he recalled.

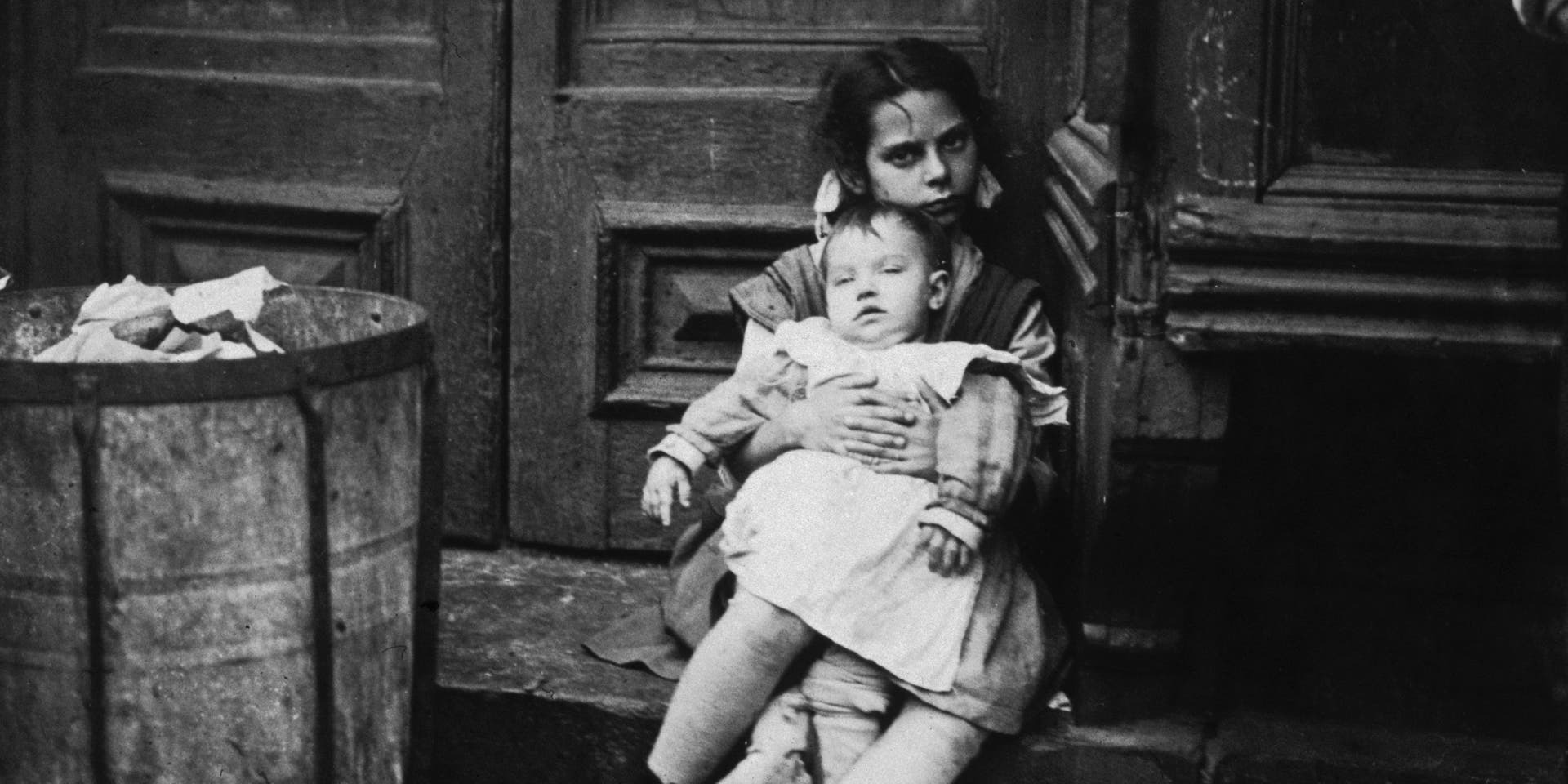

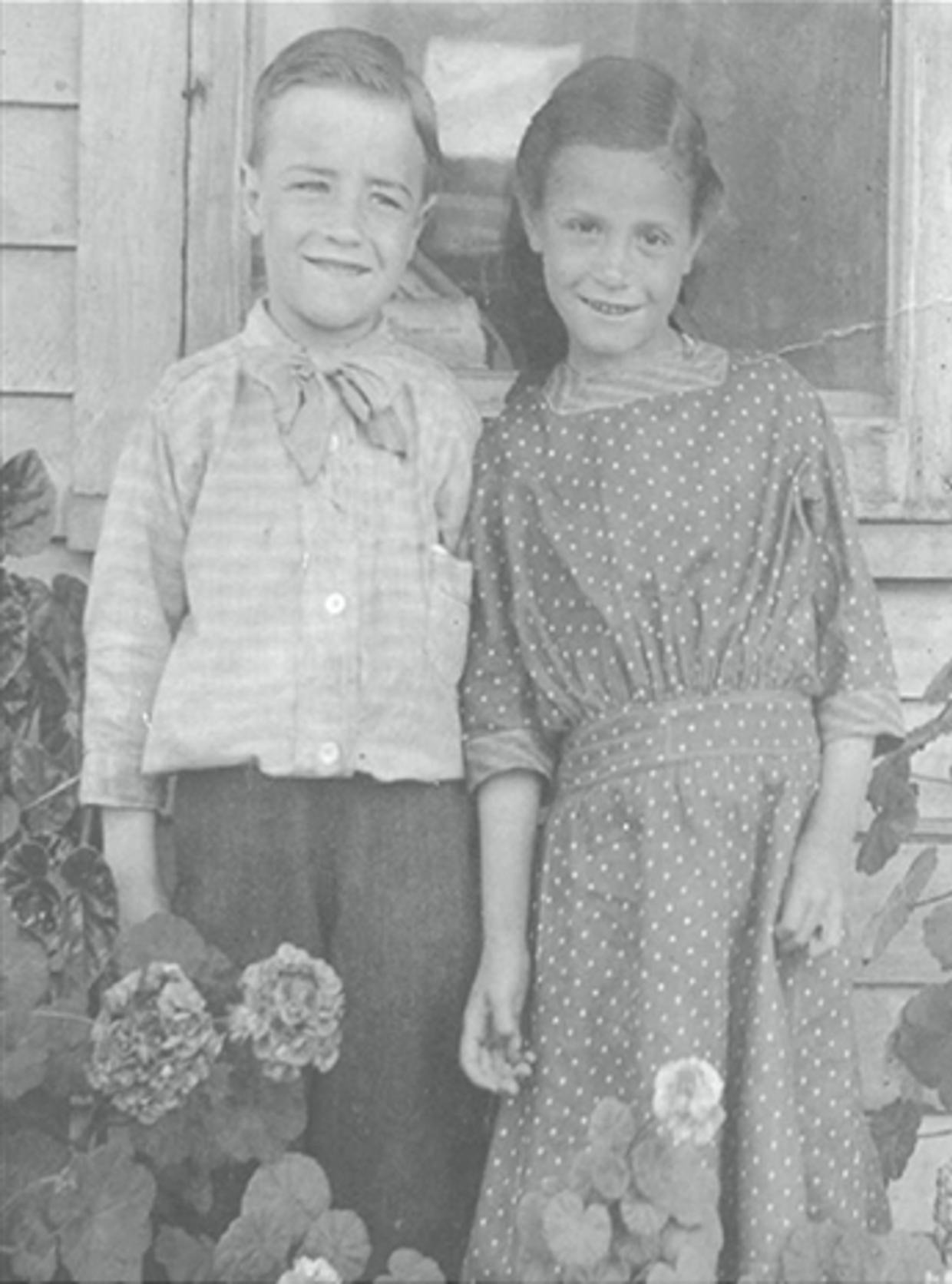

Upon arrival, placement into new families was often chaotic.

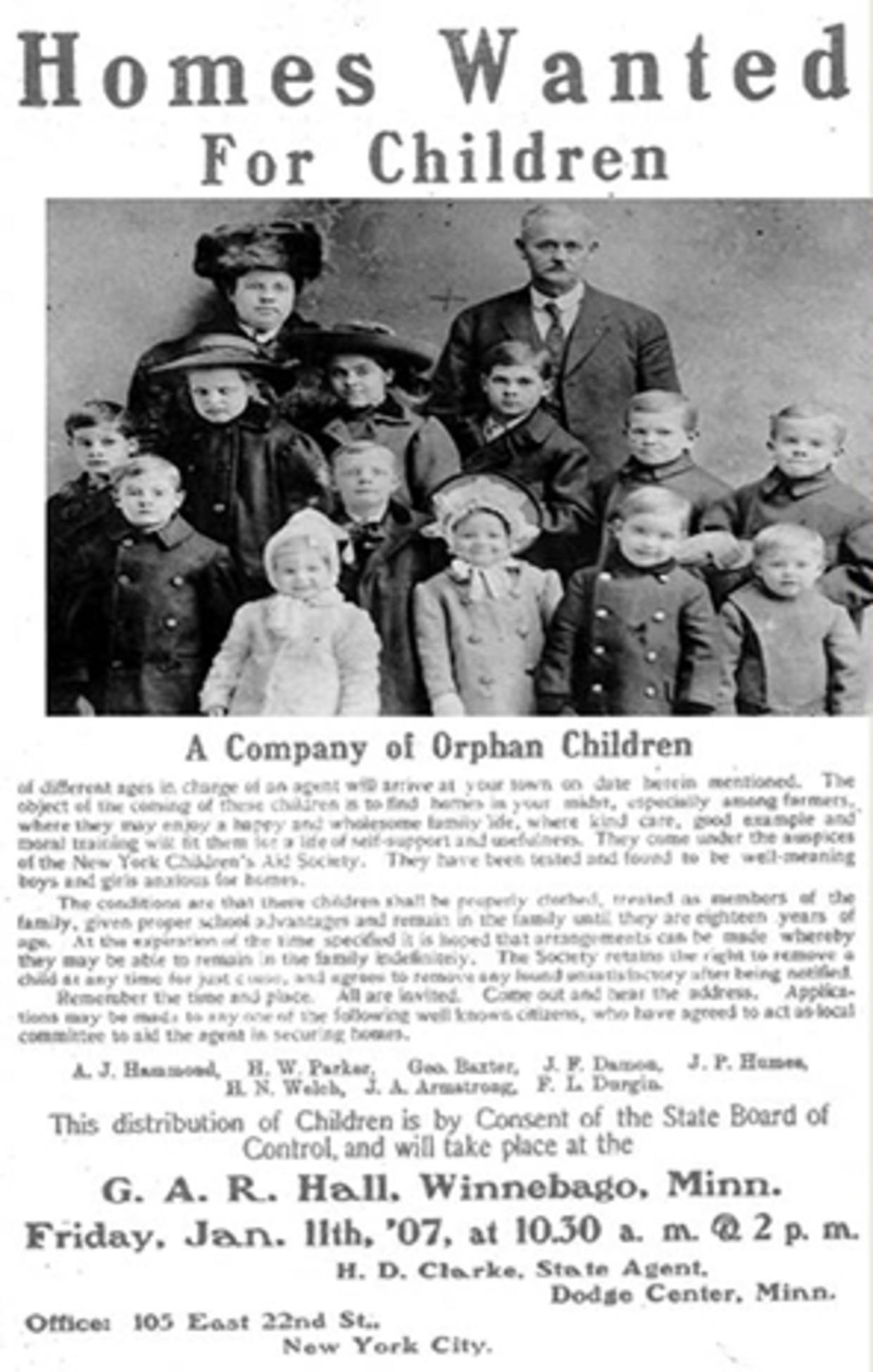

Handbills advertised “cargoes of needy children,” and as trains pulled into towns, the children were paraded before potential adoptive parents at local town halls or churches.

Prospective parents would inspect the children, much like they would livestock, deciding which ones were best suited for their homes and farms.

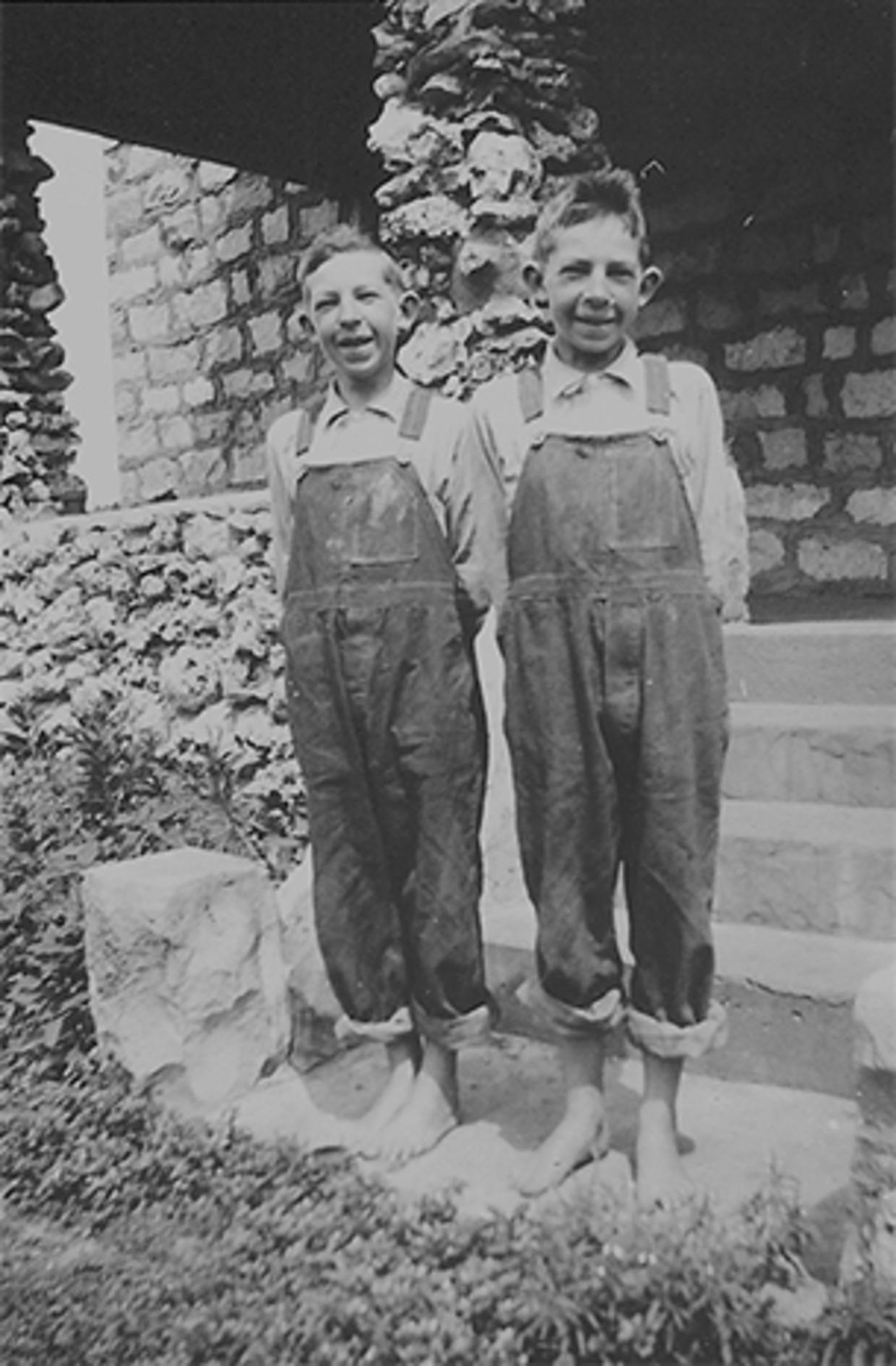

Some families welcomed the children with open arms, but others saw them as free labor.

Elliot remembers the unsettling experience clearly. A farmer approached him, feeling his muscles, and said, “Oh, you’d make a good hand on the farm.”

But Elliot responded, “You smell bad. You haven’t had a bath, probably, in a year.” When the farmer tried to take him, Elliot bit and kicked him.

Labeled as uncontrollable, he sat alone in tears, but he eventually found a home where he was loved and cared for.

A life of labor or love?

The Orphan Train Movement was often hailed as a progressive solution to child homelessness, but it brought both successes and challenges.

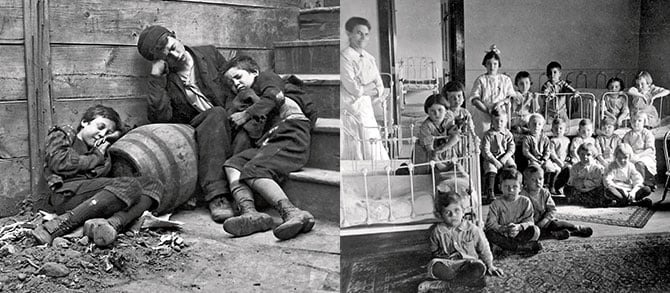

On one hand, thousands of children found loving homes and opportunities they would have never had in the overcrowded, dangerous streets of the cities.

Success stories, like those of Andrew Burke and John Brady—two former orphan train riders who became governors of North Dakota and Alaska—often highlight the program’s achievements.

However, not all children were so fortunate. Some were treated more like servants than family members, with abuse and neglect not uncommon.

As one orphan train rider, Hazelle Latimer, recounted, she was once examined “like a horse,” and taken in by a farmer who saw her more as a workhorse than a daughter.

The end of the Orphan Train era

By the early 1900s, changing views on child welfare and labor brought the orphan train era to a close.

New laws were passed that stopped children from being moved across state lines without proper supervision.

The federal government also began to get more involved in child welfare, starting with the U.S. Children’s Bureau, which was founded in 1912.

The last orphan train departed in 1929, marking the end of a chapter in American social history.

By that time, the foster care system had started to develop, and orphanages were undergoing reforms to better protect children.

The legacy of the Orphan Trains

Today, it’s estimated that over two million Americans are descendants of orphan train riders. The legacy of this movement lives on through the stories passed down in families.

Museums like the National Orphan Train Complex in Concordia, Kansas, and documentaries such as “The Orphan Trains” help ensure these children’s stories aren’t forgotten.

As Charles Loring Brace once wrote, “When a child of the streets stands before you in rags, with a tear-stained face, you cannot easily forget him.”