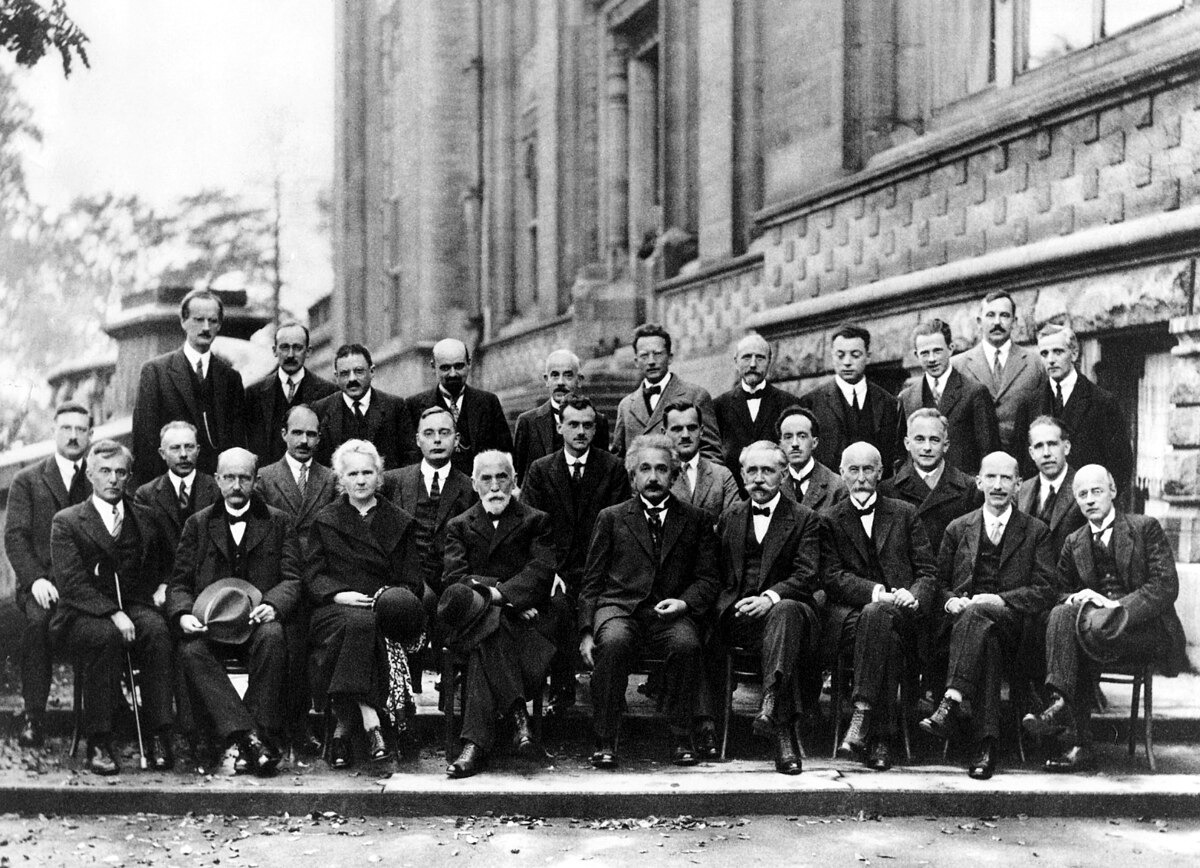

“The Most Intelligent Photo Ever Taken”: The 1927 Solvay Council Conference Featuring 17 Nobel Prize Winners

In 1927, a historic gathering took place in Brussels. The Fifth Solvay Conference, attended by some of the most brilliant scientific minds of the 20th century, became a defining moment in the struggle between classical physics and the emerging quantum theory.

Among the 29 attendees, 17 would go on to win Nobel Prizes, including legendary figures such as Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, and Marie Curie.

This iconic photograph of the event has often been dubbed “the most intelligent photo ever taken,” and for good reason.

The Solvay Conference: A Meeting of Scientific Giants

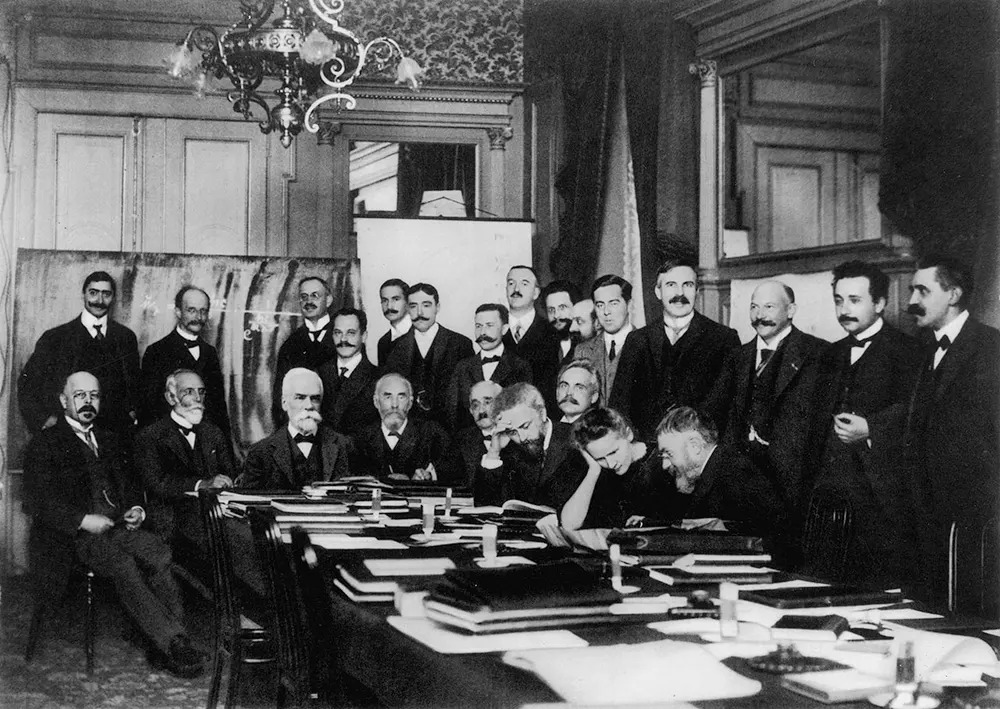

The Solvay Conference, established by Belgian industrialist Ernest Solvay in 1911, brought together leading physicists and chemists to discuss the most pressing unresolved problems in science.

The 1927 edition, held in Brussels, focused on electrons and photons, two central elements in the new and contentious field of quantum mechanics.

The gathering was more than just a meeting of scientists—it was a pivotal moment in the history of science, where revolutionary ideas about the nature of the universe collided with more traditional views.

Back to front, left to right:

Back: Auguste Piccard, Émile Henriot, Paul Ehrenfest, Édouard Herzen, Théophile de Donder, Erwin Schrödinger, JE Verschaffelt, Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg, Ralph Fowler, Léon Brillouin.

Middle: Peter Debye, Martin Knudsen, William Lawrence Bragg, Hendrik Anthony Kramers, Paul Dirac, Arthur Compton, Louis de Broglie, Max Born, Niels Bohr.

Front: Irving Langmuir, Max Planck, Marie Curie, Hendrik Lorentz, Albert Einstein, Paul Langevin, Charles-Eugène Guye, CTR Wilson, Owen Richardson.

The Nobel Prize Winners

The Solvay Conference was not just remarkable for its debates but also for the incredible concentration of intellectual power. Of the 29 attendees, 17 either already held or would later be awarded Nobel Prizes. Among them were:

Marie Curie, the only person to win Nobel Prizes in two different scientific fields (Physics and Chemistry).

Albert Einstein, who had already won the Nobel Prize in 1921 and would go on to develop the general theory of relativity.

Niels Bohr, whose work on the structure of the atom earned him the Nobel Prize in 1922.

Werner Heisenberg, who formulated the Uncertainty Principle and would win the Nobel Prize in 1932.

Erwin Schrödinger, known for his famous wave equation and later for the thought experiment involving Schrödinger’s cat.

These scientists were not only innovators in their fields but also pioneers who laid the foundation for modern physics.

The Struggle Between Classical Physics and Quantum Mechanics

The 1927 Solvay Conference was more than just a gathering of brilliant minds; it marked the culmination of a larger battle between classical physics, rooted in Newtonian mechanics, and the emerging world of quantum theory.

Figures like Einstein and Max Planck were initially skeptical of the new quantum ideas, as they appeared to contradict long-standing principles of determinism.

On the other side were Bohr, Heisenberg, and Schrödinger, who embraced the uncertainties and probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics.

As physicist Max Born famously stated, quantum mechanics “ended determinism in physics” and opened the door to a new understanding of the microscopic world.

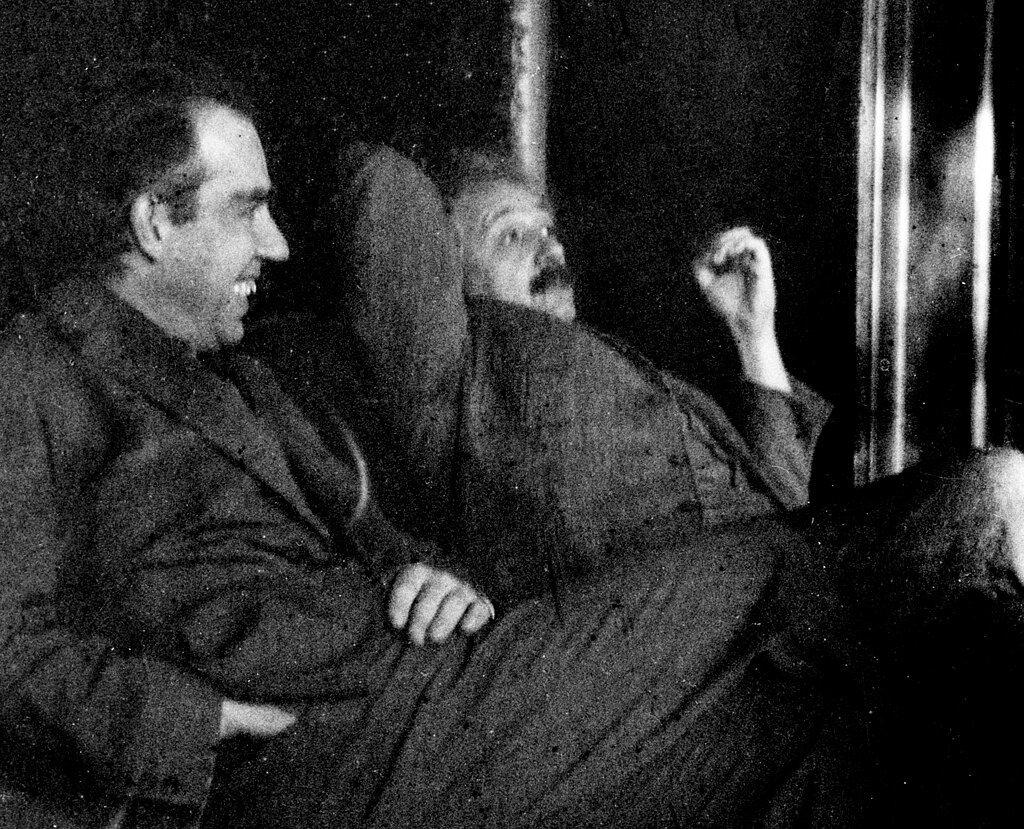

Einstein vs. Bohr: The Clash of Ideas

One of the most famous and lasting debates to emerge from the 1927 Solvay Conference was between Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr.

Einstein, who strongly believed that everything in nature follows clear, predictable rules, didn’t agree with the idea that randomness plays a role in how the universe works.

In fact, he famously said, “God does not play dice,” to express how uncomfortable he was with the unpredictable nature of quantum theory.

Niels Bohr, a key figure in quantum mechanics, shot back with, “Stop telling God what to do,” a witty retort that captured the growing divide in physics.

This exchange symbolized the tension between traditional scientific realism and the newer, less intuitive principles of quantum mechanics, a debate that continued to influence scientific thought for decades.