Exploring History Behind The Luddite Movement

For those who love history, there’s a fine line between learning and living it. Many history enthusiasts enjoy experiencing antiques and items from the past. Some even resist modern technology, finding its complications outweigh its benefits.

These individuals are often called Luddites, a term that has been used for a long time. But who were the original Luddites? And why do we call people who prefer the old ways by this name?

Keep reading as we unveil the history behind the Luddite movement.

The birth of the Luddite movement (1811-1812)

The Luddite movement emerged in the early 19th century, particularly between 1811 and 1812. This period marked the initial outburst of workers’ frustrations, mainly weavers and textile artisans, in the English Midlands, Yorkshire, and Lancashire.

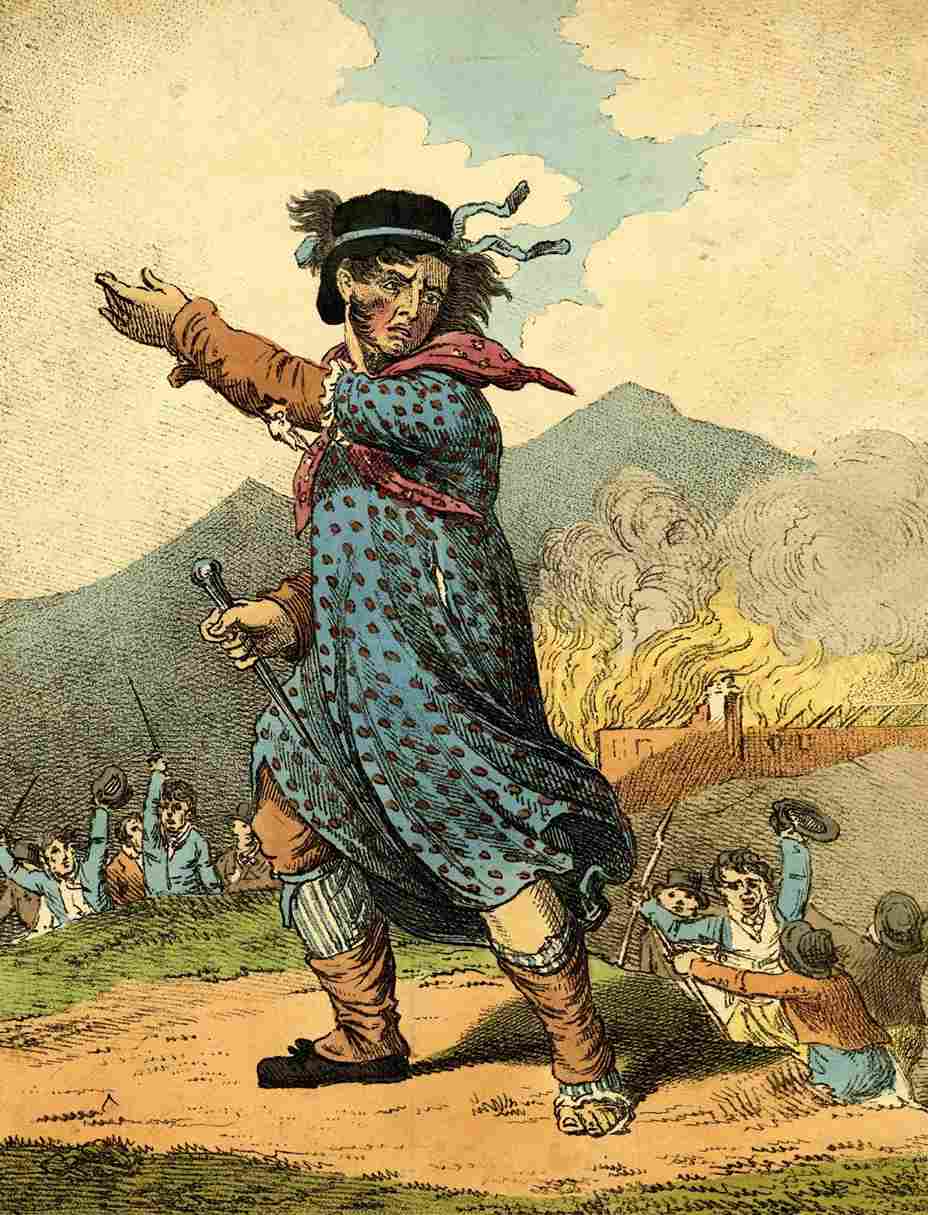

The Luddite movement got its name from a fictional leader, Ned Ludd, who supposedly destroyed weaving machinery in a rage. Protestors claimed to follow “General Ludd,” issuing manifestos and threatening letters under his name.

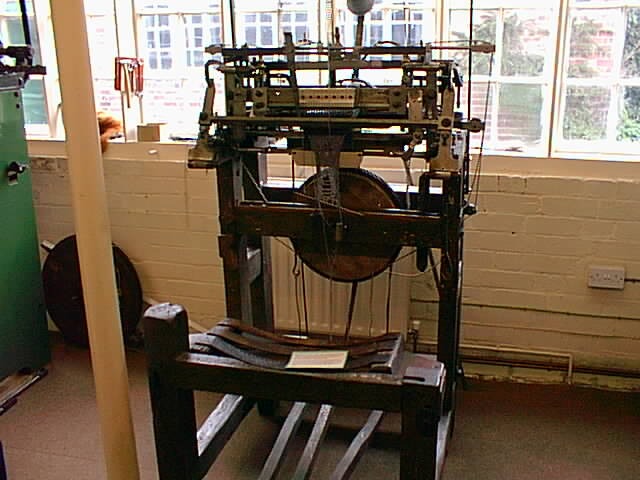

Luddites protested against the introduction of mechanized looms, knitting frames, and unskilled machine operators, fearing these threatened their jobs and livelihoods.

Between 1811 and 1816, widespread inflation and rising food costs from the Napoleonic Wars left many workers struggling to find work. Protests erupted in textile towns in the Midlands and Yorkshire, where jobs had become scarce. The decline in demand for men’s stockings and lace further reduced job opportunities.

Affordable fabric goods were in demand, leading to new machines for easier production. Innovations included textile printing and improved stocking-making machines.

The movement began with isolated machine-breaking incidents, escalating to organized attacks. The first major acts of machine-breaking occurred in Nottingham in 1811 and quickly spread across the English countryside.

Peak of Luddite activities (1812-1813)

The peak of the Luddite movement occurred between 1812 and 1813. During this period, the Luddites’ actions became more coordinated and widespread.

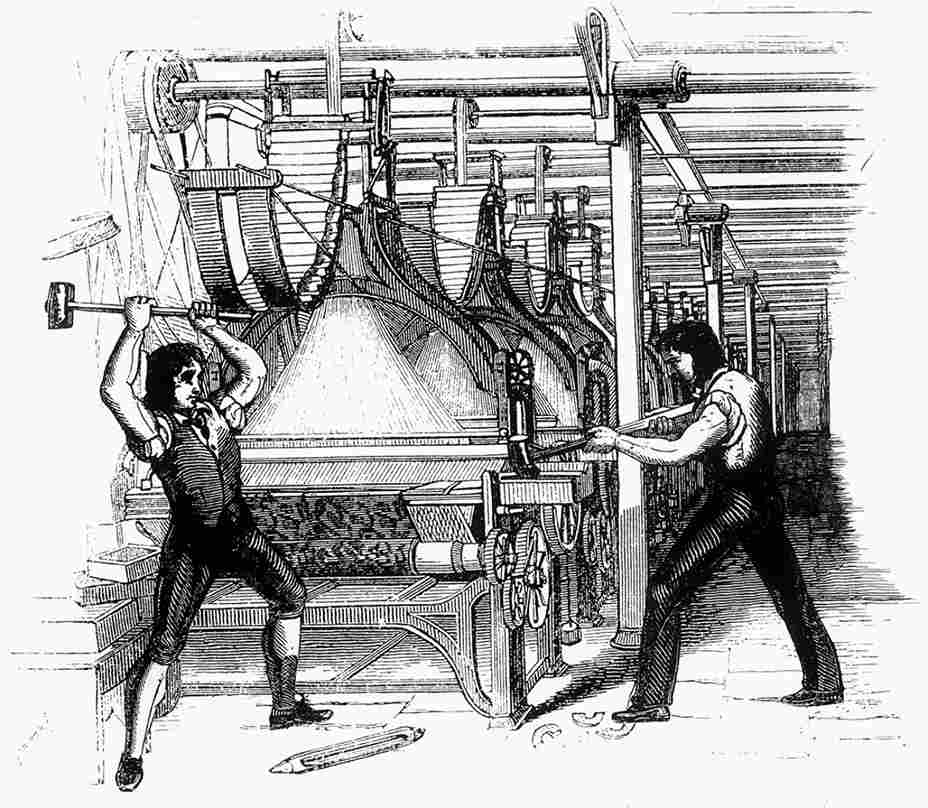

Large groups of machine-breakers, often under the cover of night, would attack factories and mills, smashing machines and occasionally engaging in violent confrontations with mill owners and local authorities.

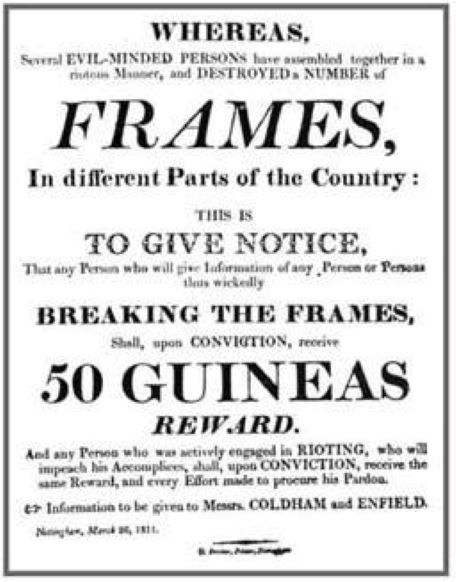

The Luddites aimed to stop employers from using expensive machinery, but the British government quickly took harsh measures. The Frame Breaking Act of 1812 made destroying machinery a crime punishable by death.

This period was filled with intense conflict and numerous trials. The unrest peaked in April 1812 when several Luddites were shot during an attack on a mill near Huddersfield.

In the following days, the army deployed thousands of troops to capture these rebels, resulting in dozens being hanged or sent to Australia.

Decline and repression of the movement (1813-1817)

By 1813, the Luddite movement began to decline due to the increasing government crackdown. The combination of military force, legal repression, and the execution of prominent Luddite leaders significantly weakened the movement.

The trial and subsequent hanging of several key figures, such as the trial in York in 1813, where 17 Luddites were sentenced to death, served as a deterrent to further activities.

Although sporadic acts of machine-breaking continued until 1817, the movement had lost much of its momentum and organizational capacity.

The Luddite movement highlighted the profound impact of industrialization on traditional crafts and the resistance of workers to technological changes perceived as threats to their employment.

The term “Luddite” has since evolved to describe individuals or groups opposing technological advancement. It wasn’t until the 20th century that their name reappeared in popular language as a synonym for “technophobe.”