The Imposible Tale Of Betty Robinson, The Olympian Who Rose From The Dead To Win Gold Medalist

There was a time when the name Betty Robinson faded from memory, and the significance of this American track prodigy seemed lost. But history has a way of reminding us, especially when it comes to the most magical legs in the world of athletics.

The day was bitterly cold, and Betty was running late, trying to catch the train. Her science teacher was certain she wouldn’t make it. Yet, to his amazement, Betty suddenly sat down next to him.

How had she managed it? That moment marked the beginning of Betty’s incredible journey to becoming the fastest woman in the world.

The Olympics are full of inspiring stories, but few are as extraordinary as Betty’s. Against all odds, she defied death itself to compete on the world’s biggest stage.

The train ride to destiny

Betty Robinson was born on August 23, 1911, in Riverdale, Illinois. She was a cheerful girl who enjoyed acting in school plays, playing the guitar, and running in local races.

Running for competition? That had never crossed her mind. In a 1984 interview with the Los Angeles Times, Betty reflected, “I had no idea that women even ran then. I grew up a hick.”

That all changed on one chilly day when Betty was running late for her train. Her science teacher, Charles Price, was also at the station, waiting for the same train.

Charles was a former runner and head coach of the boys’ track team at Thornton Township High. He noticed how quickly Betty was sprinting toward the train but didn’t think she’d make it in time.

To his surprise, as the train doors closed, Betty sat down right next to him, not even out of breath. Roseanne Montillo, who researched Betty’s story, wrote,

“When [Charles] got on the train, as the door closed, he was really surprised to find this young woman – Betty – sitting right next to him. So he knew that he had someone really, really special on his hands.”

This unexpected run marked the beginning of Betty’s journey to becoming the fastest woman in the world.

The road to Olympic dreams

Charles encouraged Betty to train with the boys’ team, as the school had no girls’ track team. The day after her race for the train, he timed her running 50 yards down a hallway.

He couldn’t believe how quick she was. Betty’s natural talent quickly propelled her into competitive racing, and just a few weeks after that fateful train run, she entered her first race.

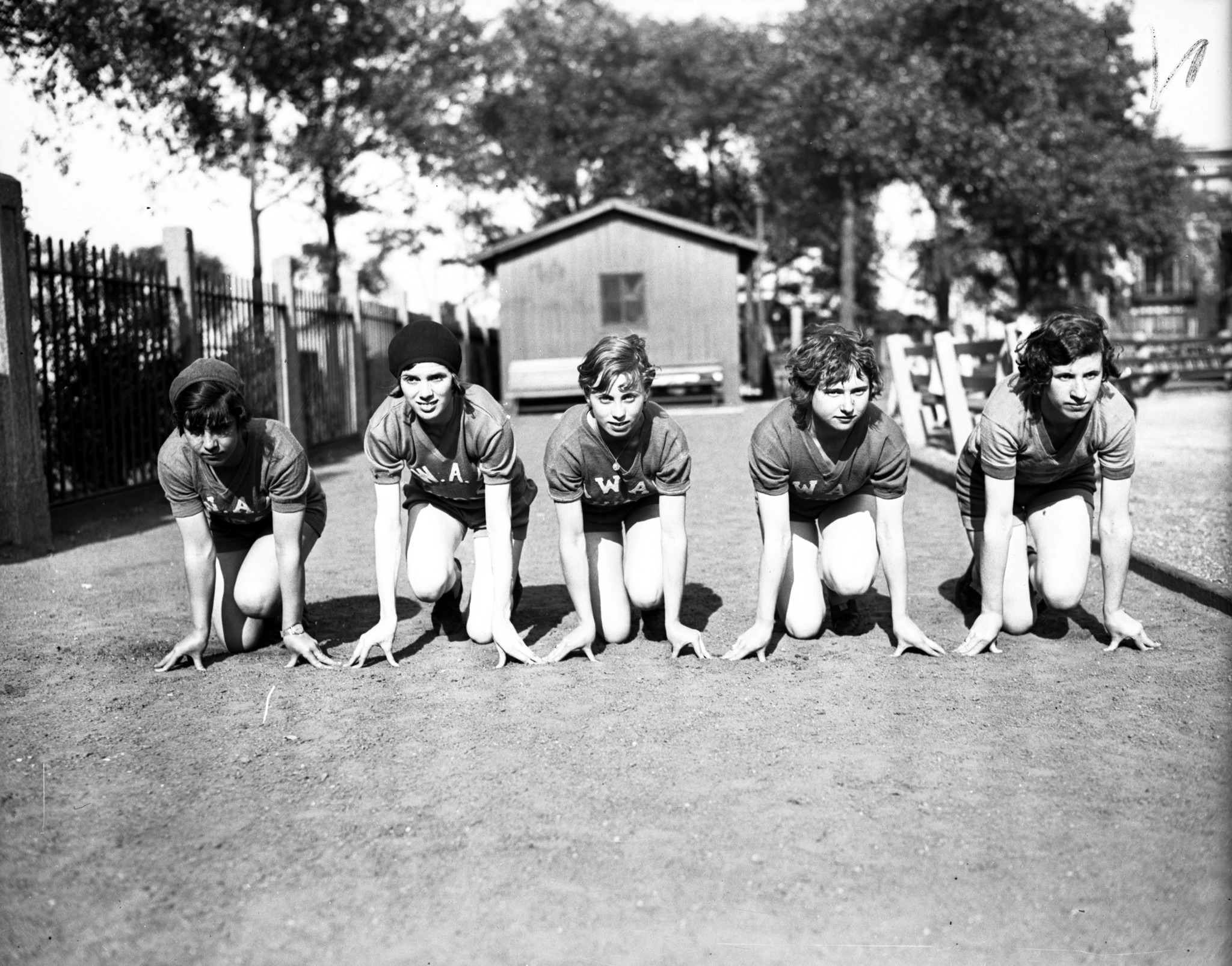

Although Betty lost her first race to Helen Filkey, the American 100-meter record holder, she was immediately invited to join the Illinois Athletic Women’s Club.

In her second 100-meter race in Chicago on June 2, 1928, Betty beat Helen and recorded a time of 12 seconds, bettering the official world record. However, it wasn’t ratified due to wind assistance.

Betty traveled to Newark, New Jersey, for the Olympic trials a month later. Competing three times in an hour, she finished second in the final, earning her spot on the American team for the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam—the first Olympics to include women’s track and field events.

Breaking records and shattering expectations

She remembered enjoying every minute of the nine-day voyage on the SS President Roosevelt from New York to Amsterdam. The American Olympic team was made up of 280 people, including 18 female track and field athletes.

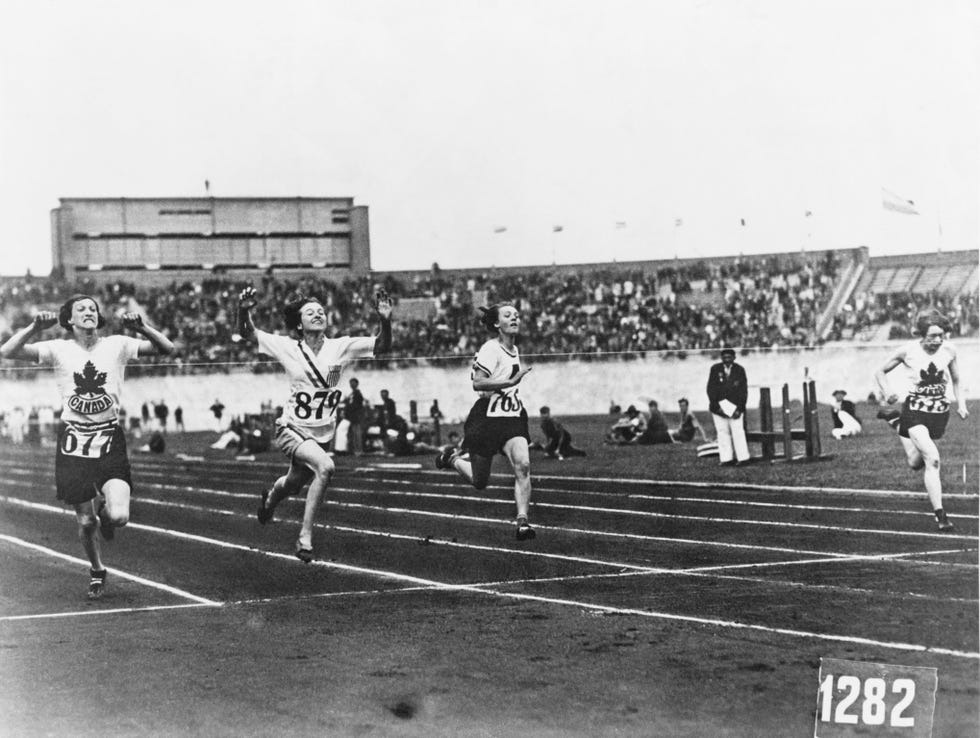

By the time she arrived in Amsterdam, Betty was already a rising star, but she still had to prove herself on the world stage. Of the four American women competing for a spot in the 100-meter final, only 16-year-old Betty made it through. She lined up against three Canadians and two Germans.

Her biggest competition was 24-year-old Canadian Fanny Rosenfeld, who had broken several national records and had defeated Betty in one of the heats.

Even though Betty was inexperienced, she seemed calm as she lined up for the final race. Her underlying nerves only showed when she arrived at the start line with two left shoes.

The start was chaotic, but Betty ran her best race. She won the gold medal in a time of 12.2 seconds, either equaling or breaking the world record, depending on the listing. Betty had been a runner for just five months, and now she was an Olympic champion.

“I can remember breaking the tape, but I wasn’t sure that I’d won. It was so close. But my friends in the stands jumped over the railing and came down and put their arms around me, and then I knew I’d won. Then, when they raised the flag, I cried,” Betty later recalled.

The dreadful brush with death

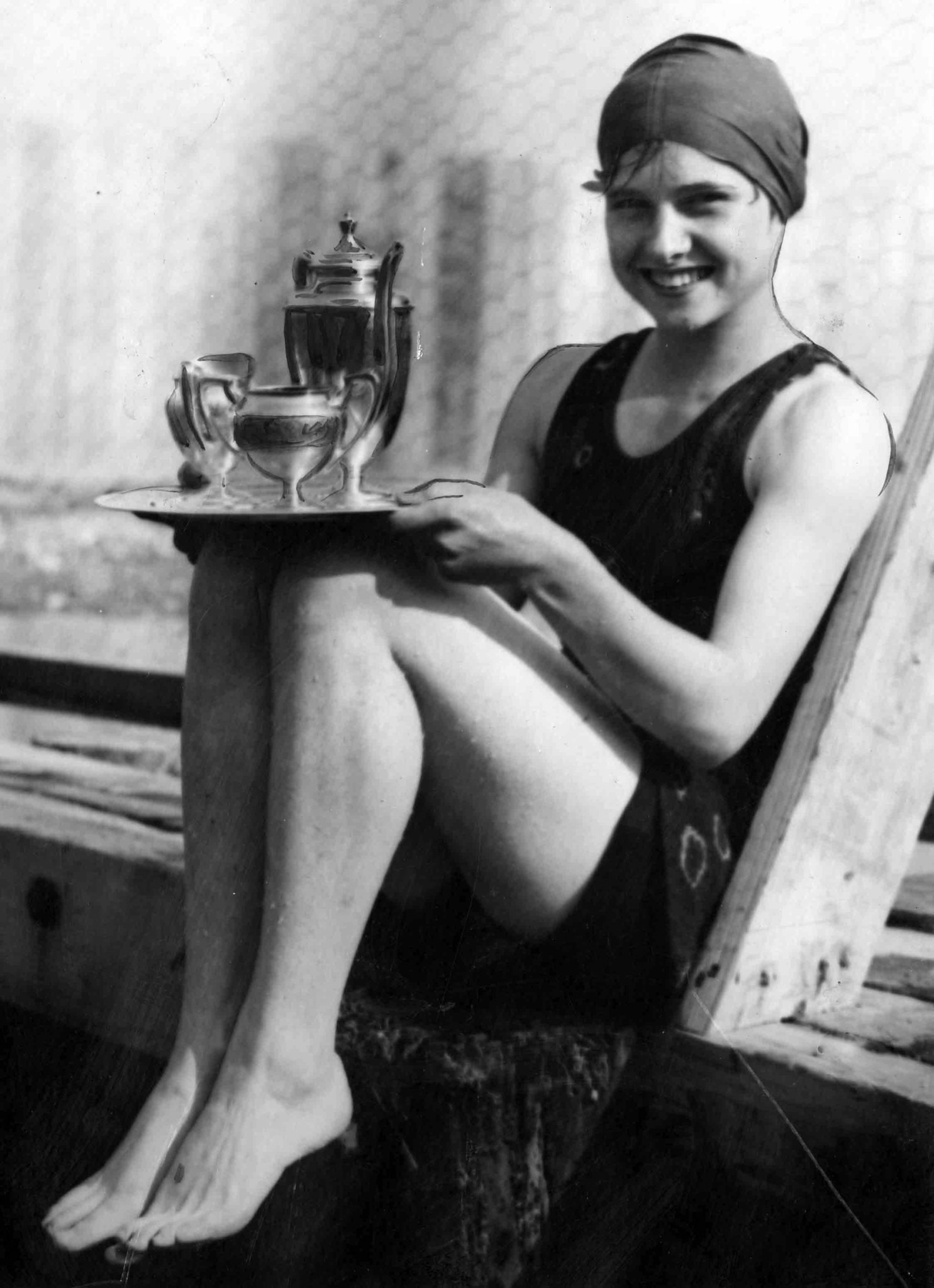

Betty returned home to Riverdale as a hero, greeted by huge crowds and celebrated with parades and gifts. After the excitement died down, she went back to high school and later started a degree in physical education at Northwestern University, with plans to coach the 1936 Olympic team.

But in 1931, Betty’s life took a tragic turn. On a scorching day, she asked her cousin, a part-owner of a small plane, if she could take a flight to cool off. That was when a nightmare going to come. The plane’s engine stalled, and it nosedived into a marshy field.

Betty was pulled from the wreckage, unconscious and nearly unrecognizable. She was believed to be dead and was already taken to a mortuary. But miraculously, the staff realized she was still breathing and quickly taken to a nearby hospital.

She was unconscious for seven weeks and couldn’t walk normally for two years. Doctors were certain she would never run again.

But Betty insisted “Of course I am going to try to run again”. Her recovery was slow and painful, but her pre-accident training helped her regain strength. She eventually returned to the Illinois Athletic Women’s Club to begin training for the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

The impossible comeback

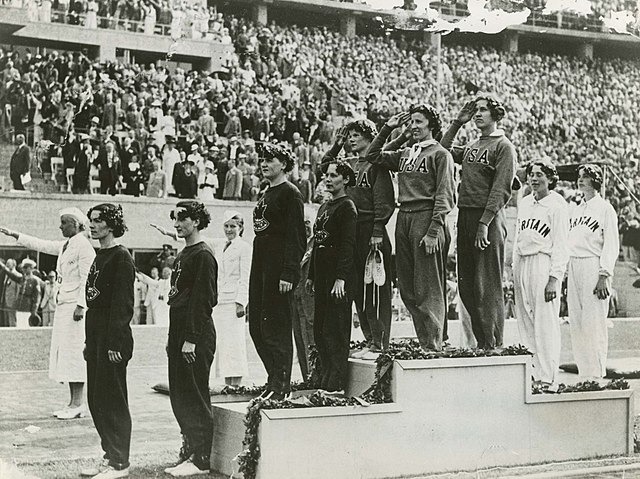

Jesse Owens’ four gold medals from the 1936 Olympics are legendary, but Betty Robinson’s comeback story is just as remarkable.

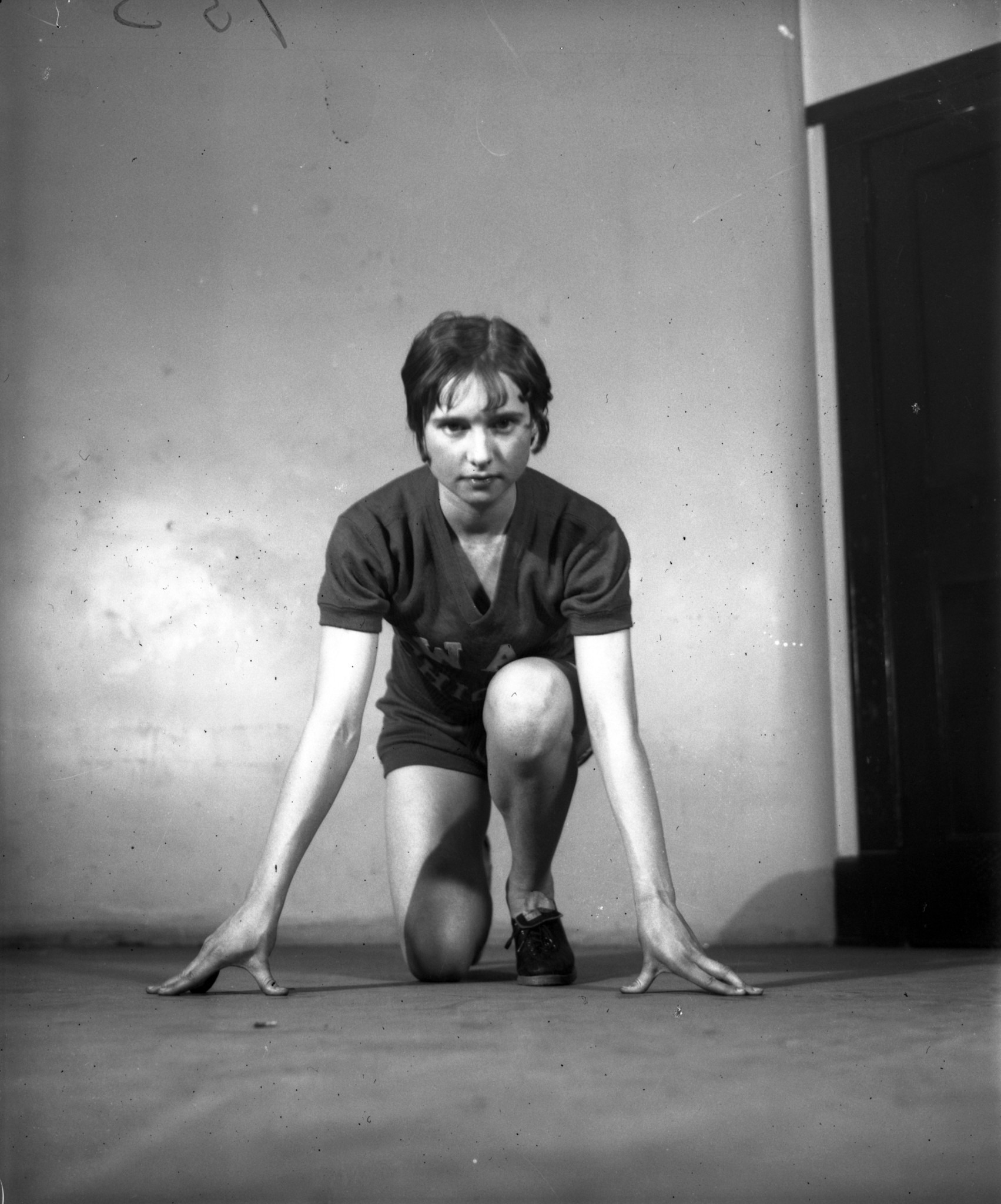

She secured a spot on the 4×100 meter relay team, though she couldn’t compete in the individual 100-meter race because she couldn’t crouch at the start.

In the final relay, the German team held a nine-meter lead heading into the last leg. However, a fumbled handover disqualified them, and Betty’s team took the victory, finishing in 46.9 seconds.

Betty earned her second Olympic gold, which she shared: “It’s indescribable how lucky I felt to be there and getting another medal.”

After the 1936 Games, Betty retired from competitive running but stayed connected to the sport as an AAU timekeeper and public speaker.

She settled in Glencoe, Chicago, where she worked in a hardware store, raised two children, and remained humble about her achievements. She carefully kept her medals tucked away in a Russell Stover’s sweet box.

One last moment in the sun

In 1996, at 84 years old, Betty was honored to carry the Olympic torch for a few blocks on its way to Atlanta for the Games. Frail but determined, she carried the torch without assistance, enjoying the moment just as she had decades earlier.

Betty Robinson passed away on May 17, 1999, in Denver, Colorado, at the age of 87.

Her journey paved the way for women’s sports, proving that with determination and resilience, anything is possible. As her granddaughter once said, “She loved to run and wanted others to be able to do what they loved just as she had.”