The Heartbreaking Story Of Joseph Merrick, The Elephant Man, Who Sought Normal Life

Joseph Merrick’s life story is one of history’s most tragic and haunting. Born with severe physical deformities that dramatically enlarged his head and limbs, Merrick became known as “The Elephant Man” in the late 19th century.

His unique appearance made him a “freak show exhibit” before he found a more dignified life at London Hospital, where he died in 1890.

Joseph Merrick’s dramatic and unusual transformation

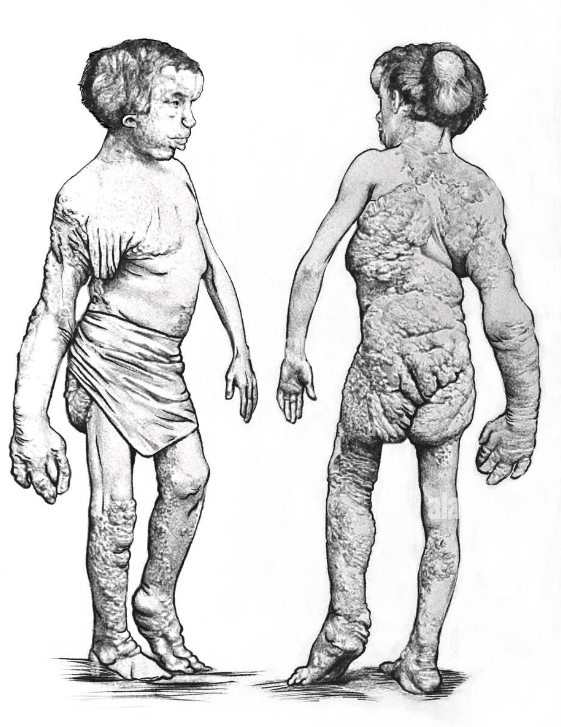

Born on August 5, 1862, in Leicester, England, Joseph Merrick began life as a healthy child. But over time, his body underwent dramatic and unsettling changes.

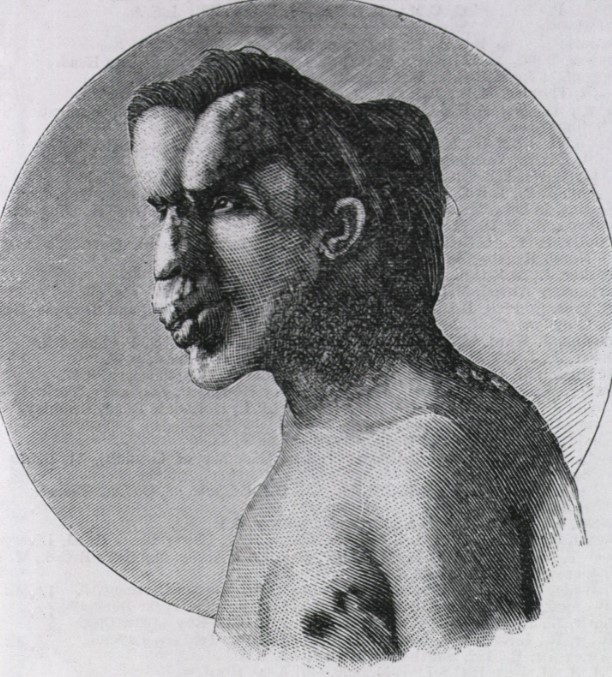

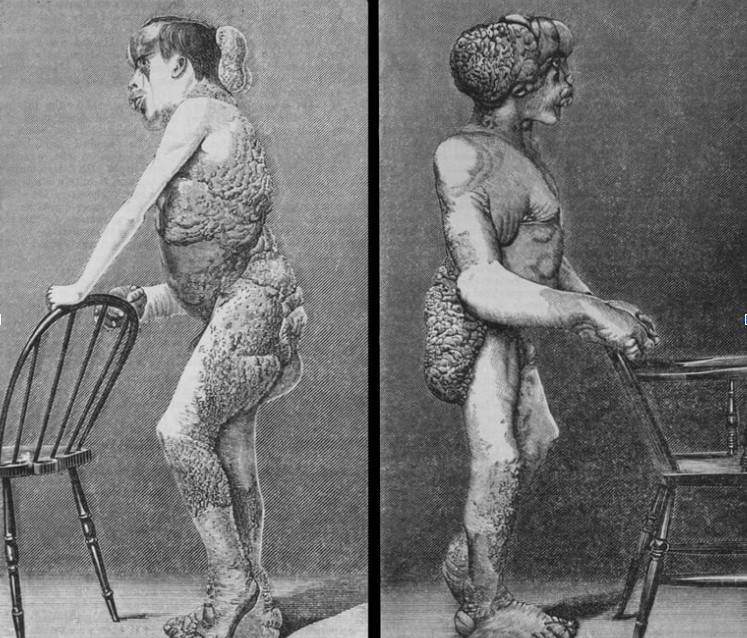

His lips swelled unnaturally, his once-smooth skin turned gray and coarse, and a lump formed on his forehead. A mass of excess flesh grew at the back of his neck, and his feet became unusually large.

While his left arm remained normal, his right arm twisted and deformed. These physical changes led Joseph to a life as a 19th-century sideshow attraction, where he became known as “The Elephant Man.”

The reason for his dramatic physical transformation

The cause of his condition baffled medical experts, and it remains an enigma even today. Despite DNA testing on his hair and bones, no clear answers have emerged. Despite lacking a medical explanation, his mother made a claim.

She remembered being shoved into the path of an animal parade while pregnant, an elephant rearing up and briefly trapping her underfoot. Terrified for herself and her unborn baby, she believed this frightening event was the reason for her son’s deformities. She shared this account with Joseph, convinced it explained the physical and emotional pain he endured throughout his life.

Alongside his severe deformities, a childhood hip injury left Joseph Merrick with a permanent limp, so he had to use a cane to walk. His life grew even darker when he lost his beloved mother to pneumonia at just 11 years old—a tragedy he later described as “the greatest misfortune of my life.”

Her death, coupled with relentless ridicule over his appearance, pushed Merrick to leave school. Overwhelmed by grief and rejection, he questioned how someone who saw his own face as “…such a sight that no one could describe it,” could endure in an unkind world.

Merrick’s disownment by his family and search for help

As if Joseph Merrick’s life wasn’t deeply miserable enough, he had to live with his very own “evil stepmother.” Soon after the death of Joseph’s mother, his father married a widow who had children of her own. His stepmother showed him no kindness, making his already difficult life even harder. Merrick later described her impact, saying, “She was the means of making my life a perfect misery.”

Sadly, his father also turned cold, leaving Merrick to face his struggles alone. Even when he tried to run away, his father always brought him back, ensuring he remained in a home where compassion was nowhere to be found.

When Joseph Merrick wasn’t in school, his stepmother insisted he bring in money. At 13, he started working in a cigar factory, but as his hand deformity worsened, the job became impossible, and he had to leave after three years.

By 16, Merrick was jobless, wandering the streets daily in search of work. When he came home for lunch, his stepmother mocked him, saying the small meal was more than he deserved.

He tried selling goods door to door from his father’s shop, but his twisted features and slurred speech scared away customers. Few would even open their doors. His father, angry at Merrick’s failures, beat him severely one day, leading Merrick to leave home for good.

Becoming ‘an exhibit’ for a living

During the 1800s, sideshows featuring so-called “human oddities” were disturbingly popular. Desperate for income, Joseph Merrick reached out to a showman named Sam Torr and joined his traveling exhibit.

It was there that he was given the name “Elephant Man” and advertised as “Half-a-Man and Half-an-Elephant” in 1884. Merrick, who wore a cape and veil in public to hide his face, often faced cruel harassment from mobs while traveling with the show.

Joseph Merrick’s journey took him through Leicester, Nottingham, and London before he eventually found himself under new management with Tom Norman, an East London shopkeeper known for showcasing human curiosities.

Norman provided Merrick with an iron bed and a curtained space for privacy, but it became clear that Merrick couldn’t lie down to sleep—his head’s immense weight could have crushed his neck. Instead, he slept upright, using his legs for support.

Outside the shop, Norman used his flair for showmanship to draw in curious visitors, promising them that the Elephant Man was “not here to frighten you but to enlighten you.”

During his time in the sideshow, Joseph Merrick wrote a brief autobiography that was distributed at his performances. Writing became a source of solace for him, and he was particularly fond of composing letters.

In fact, he often closed his letters with a poem titled “False Greatness” by Isaac Watts, a piece that seemed to resonate deeply with him.

‘Tis true my form is something odd,

But blaming me is blaming God;

Could I create myself anew

I would not fail in pleasing you.

If I could reach from pole to pole

Or grasp the ocean with a span,

I would be measured by the soul;

The mind’s the standard of the man.

Joseph’s capture of a local doctor’s attention

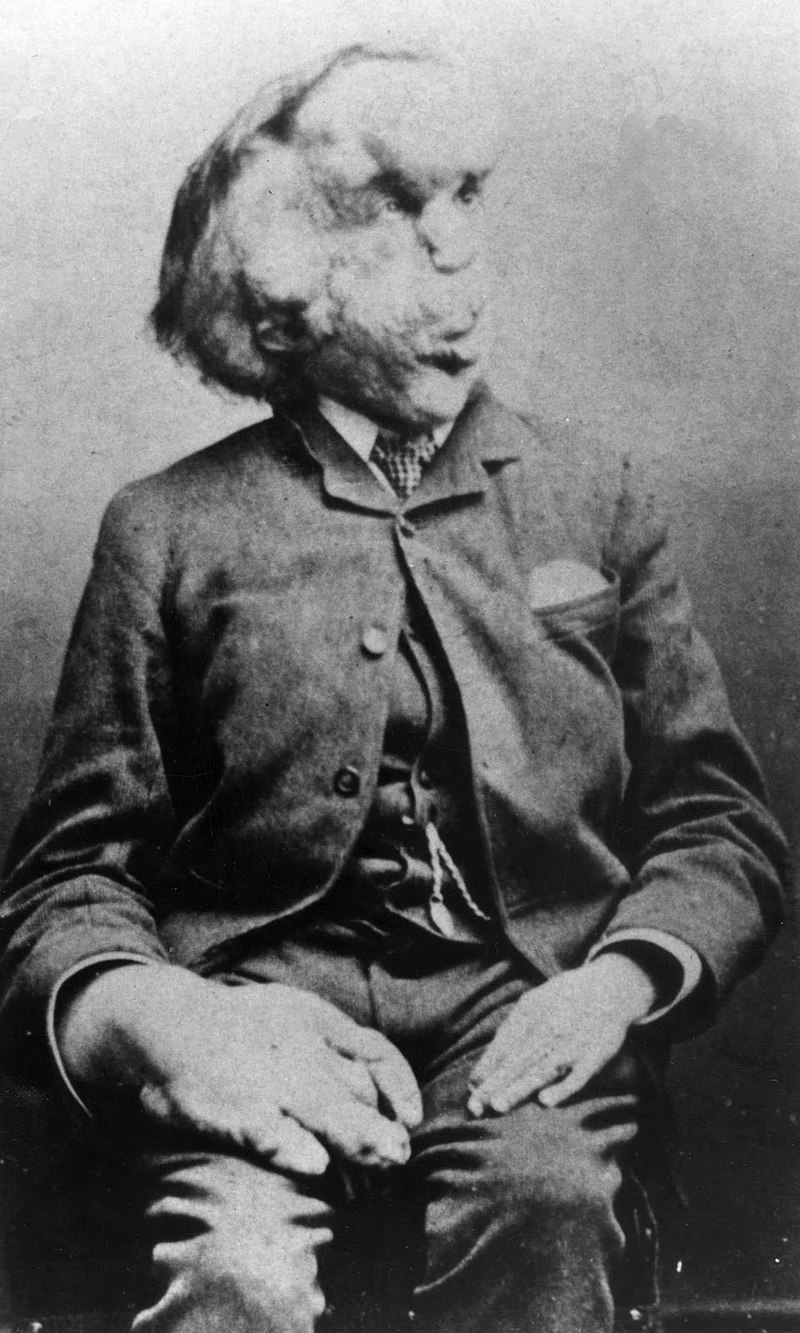

Norman’s shop was located just across from London Hospital, where Dr. Frederick Treves worked. Intrigued by Joseph Merrick, Treves arranged a meeting with him before the shop opened. What he saw both shocked and fascinated him. He later described Merrick’s head as “very, very big – like an enormous bag with a lot of books in it.”

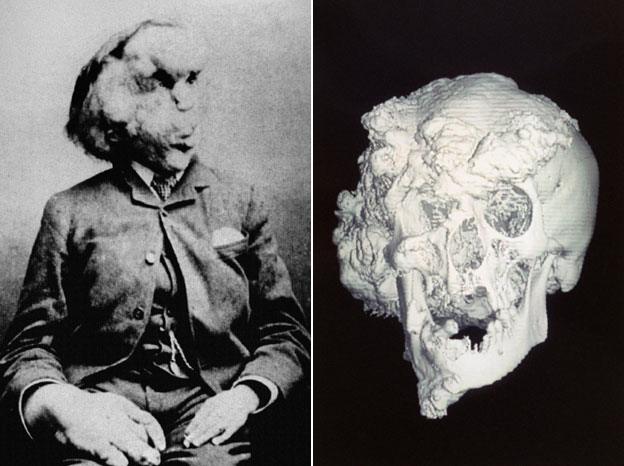

Though Merrick was generally healthy, Treves found that he had severe physical challenges. His head had a circumference of nearly a meter, his right hand was 30cm wide at the wrist, and his body was covered in tumors, making walking difficult.

The doctor presented Joseph to the Pathological Society of London, hoping to conduct further studies, but Merrick refused. He later admitted that the experience made him feel like “an animal in a cattle market.”

The worsening of his life

By the time Joseph Merrick was beginning to make some money, the popularity of “freak shows” was waning. Due to concerns about morality and decency, police were shutting down these exhibitions.

In search of more lenient laws, Merrick’s managers sent him to continental Europe. However, in Belgium, after his show failed, his promoter took all of his life savings—about $9,000 today—beat him, and left him stranded.

Alone in Belgium and desperate to return to England, Merrick finally made the long journey back after a year. When he arrived in London, he was met with a mob of people in the streets. Unable to understand him, they eventually found Dr. Treves’ business card and took Merrick to the London Hospital for care.

When Joseph was brought back to the London hospital, Dr. Treves found his condition had worsened significantly over the past two years. Initially, Joseph was given a temporary bed, but the hospital lacked the resources for long-term care.

The hospital chairman reached out to The Times, sharing Joseph’s story and asking for help. The response from the public was overwhelming, with both letters and donations pouring in. Thanks to this support, Joseph was able to stay in the hospital for the rest of his life. Dr. Treves visited him daily, and their relationship grew into a close friendship.

His death in sleep at the age of 27

Over time, Joseph Merrick’s condition caused his head to become so heavy from skin and bone growth that he couldn’t lie down to sleep without risk. On the night he passed away, however, he chose to rest in his bed, where he died in his sleep. Dr. Treves, who performed the autopsy, believed Merrick died from asphyxiation, likely from a lack of oxygen.

More than a century later, another theory emerged suggesting that the weight of his head caused his neck to dislocate, crushing his spinal cord. After the autopsy, Merrick’s skeleton was sent to Queen Mary University of London, where it was on display for many years.

Today, his remains are kept in a private room, accessible only with special permission.