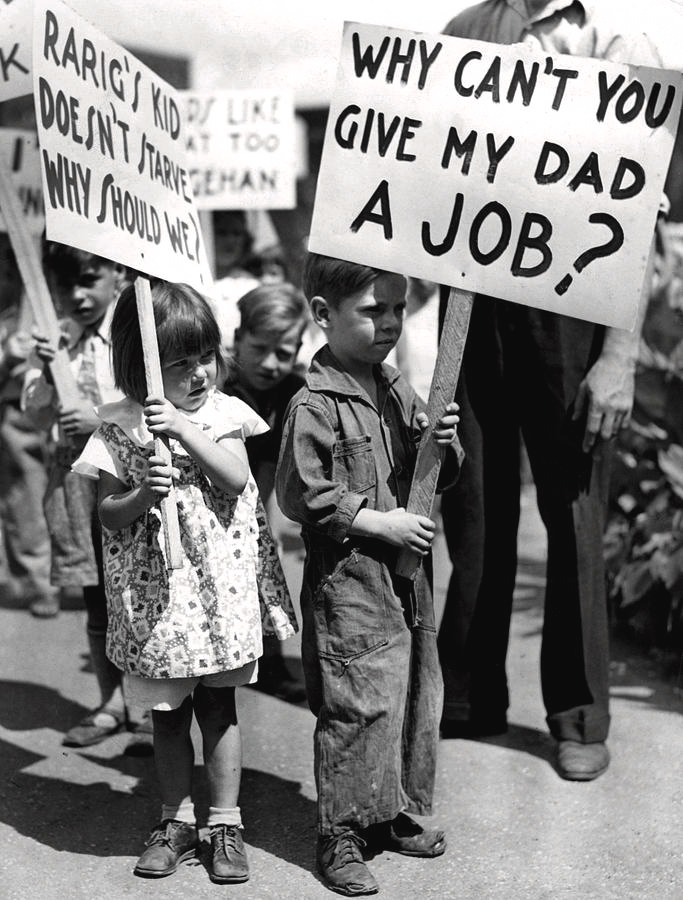

Shocking Story Behind The Iconic Photo ‘Why Can’t You Give My Dad A Job?’

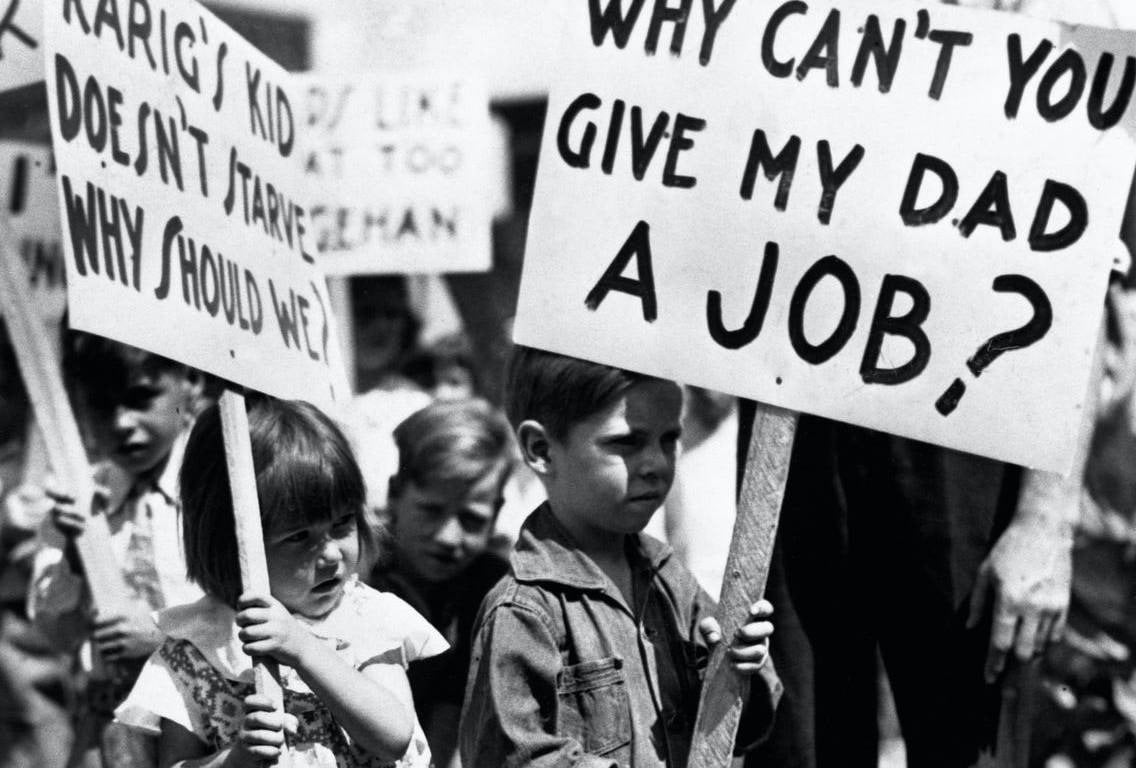

The Great Depression left an immense impact on society, vividly captured in numerous photographs. One such iconic image, often captioned “Why can’t you give my Dad a Job?” has become a powerful symbol of this era.

At first glance, the viewer sees a protest sign, but it’s the children holding the signs that make the image deeply moving.

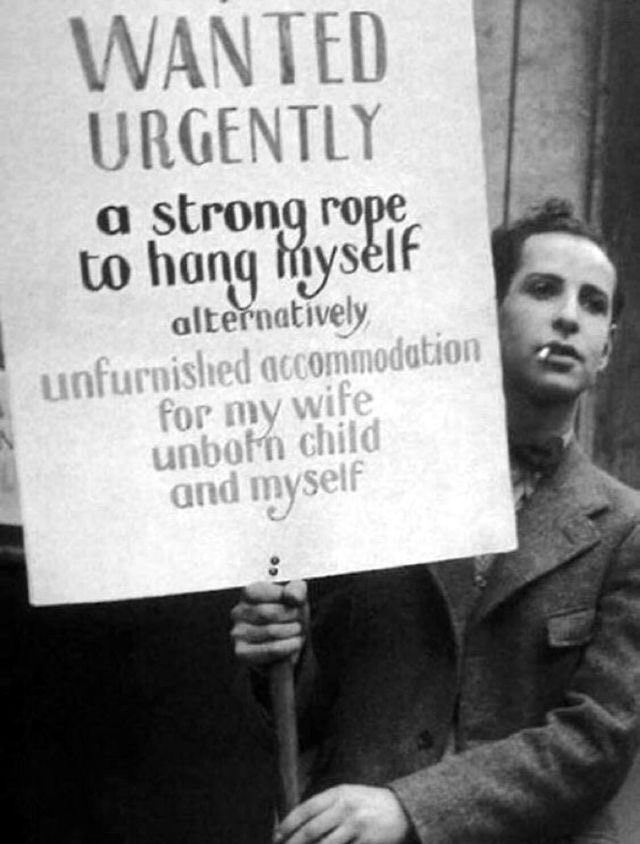

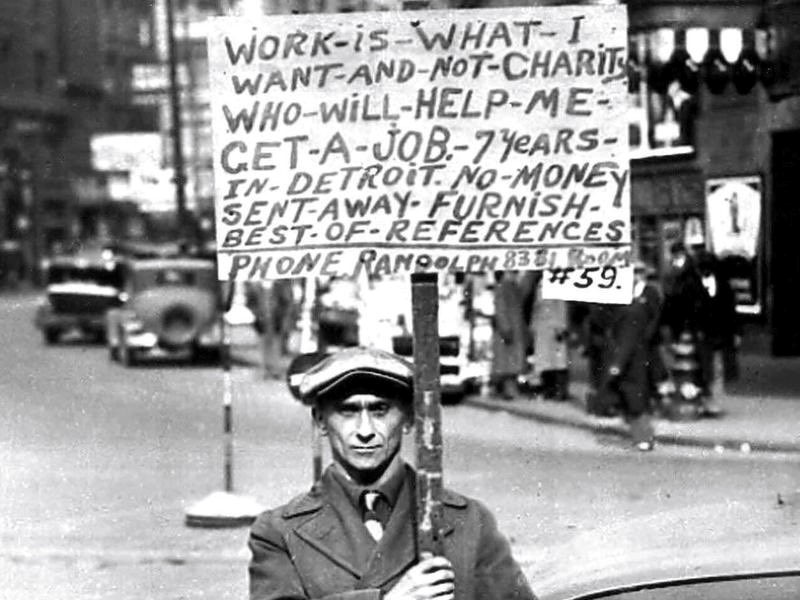

The period saw countless families struggling to survive. Children like those pictured were often directly affected by the economic downturn, watching their parents struggle to find work and provide for their families.

The photo “Why can’t you give my Dad a Job?”

The photograph is a famous image taken during the Great Depression, capturing the struggles of children and families affected by unemployment.

This particular photo is often attributed to the Farm Security Administration (FSA), a U.S. government agency created to combat rural poverty during the Great Depression.

The FSA hired photographers like Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Arthur Rothstein to document the plight of American farmers and the impact of the economic crisis.

However, without more specific details or metadata about the image, it is challenging to attribute this photograph to a specific photographer. The image is representative of the powerful documentary work done by FSA photographers during the 1930s and early 1940s.

According to some sources, the photo was taken by Daniel Hagerman in 1937. This particular photo, with its compelling composition and emotional depth, remains one of the most memorable images from the Great Depression.

An overview of the Great Depression

The Great Depression, which began with the stock market crash in October 1929, was the most severe economic downturn in the history of the industrialized world. Lasting until the onset of World War II, it profoundly affected both urban and rural populations across the United States and beyond.

The Great Depression saw a catastrophic decline in economic activity. By 1933, industrial production in the U.S. had fallen by nearly 47%, and around 15 million Americans were unemployed, representing nearly 25% of the workforce. The banking sector was hit particularly hard, with about 9,000 banks failing during the 1930s.

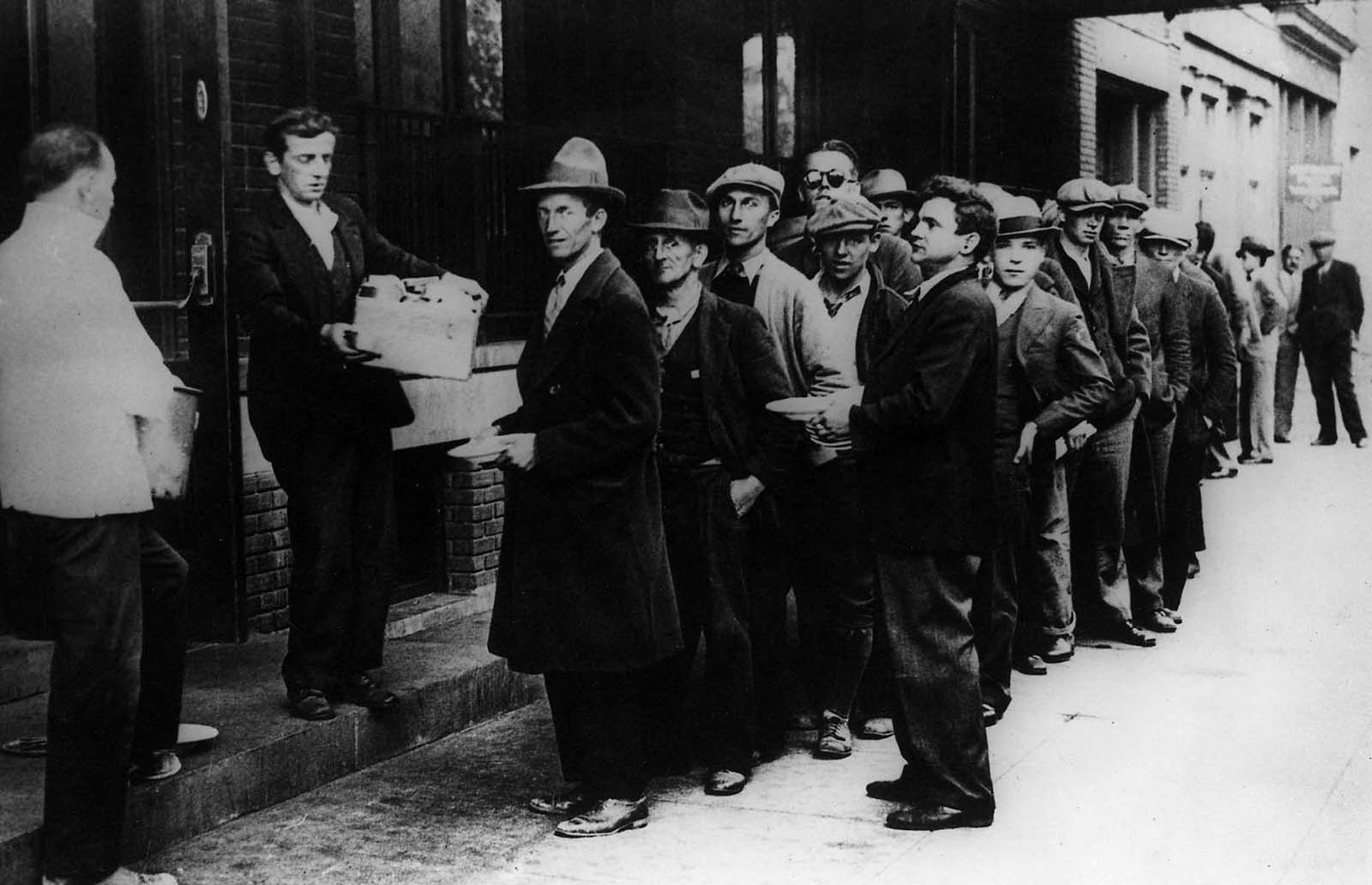

Families faced extreme hardships, often losing their homes and livelihoods. Many people lived in shantytowns known as “Hoovervilles,” named derisively after President Herbert Hoover, who was widely blamed for the economic woes.

Schools closed, and children like those in the iconic 1937 photo by Daniel Hagerman were directly affected, sometimes participating in protests to advocate for their families.

The federal government, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, launched the New Deal, a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations.

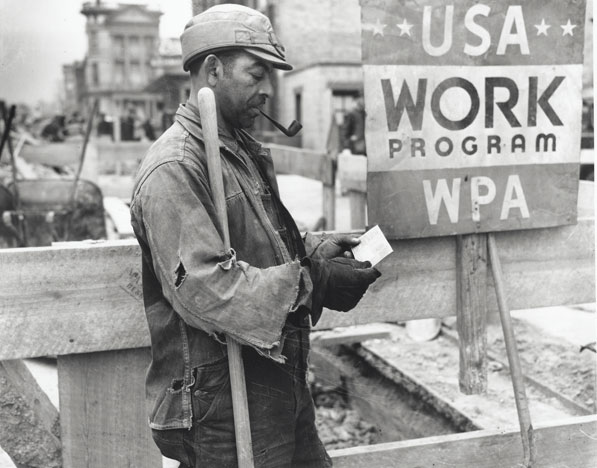

These efforts aimed to provide relief for the unemployed and those in poverty, recover the economy, and reform the financial system to prevent a future depression. Notable programs included the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and the Social Security Act.

The Great Depression also left a significant mark on American culture. Literature, music, and arts of the time often reflected the struggles and resilience of the people. Works like John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath” and songs like Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land” became cultural touchstones that illustrated the era’s hardships and hopes.

The economic boost provided by World War II ultimately ended the Great Depression. The increased demand for goods and services to support the war effort led to a surge in industrial production and job creation, pulling the U.S. economy out of its slump.

Efforts to solve unemployment

In his First Inaugural Address in 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt faced the Great Depression with a bold promise of “action and action now.”

From the start, Roosevelt made it clear that his “primary task” was getting unemployed Americans back to work. In his First 100 Days, FDR created the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) and appointed Harry Hopkins to run it.

Hopkins was instructed to provide immediate and adequate relief to the unemployed, ignoring politics. Within an hour of starting, Hopkins sent $5 million in cash relief to four million destitute families.

However, Hopkins realized that unemployed workers wanted jobs, not handouts. FERA soon offered work relief, allowing people to earn their assistance through employment.

In November 1933, Roosevelt and Hopkins launched the Civil Works Administration (CWA), providing real jobs that paid the prevailing wage. Within a month, the CWA employed four million people on over 4,000 projects.

Though temporary, the CWA showed that Americans wanted to work and provided a model for future employment programs. Hopkins later advocated for an Employment Assurance Corporation as an employer of last resort.

The Social Security Act of 1935 led to the creation of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Under the leadership of Harry Hopkins, the WPA provided millions of jobs over seven years. It was one of the New Deal’s most successful programs and only ended when the U.S. shifted its focus to the wartime economy.

The New Deal’s history offers valuable lessons for the current administration. As Harry Hopkins said, “People don’t eat in the long run, they eat every day.” Immediate employment and decent wages are crucial to combating poverty. Americans can meet their daily needs and maintain economic stability with adequate earnings.