Olavinlinna Castle: 15th-Century Stone Fortress Still Standing In Finland

Olavinlinna Castle, also known as St. Olaf’s Castle, is the northernmost 15th-century stone fortress still standing in Finland.

This fortress is located on a small island in the Kyrönsalmi strait, surrounded by the serene waters of lakes Haukivesi and Pihlajavesi.

It carries with it stories of war, peace, and resilience that have shaped the region for centuries.

Why Is The Castle Called St. Olaf’s Castle?

Olavinlinna Castle is called St. Olaf’s Castle because it was named in honor of Saint Olaf, the patron saint of Norway.

The name “St. Olaf’s Castle” reflects the castle’s historical and cultural connections to Saint Olaf, who was a significant figure in Scandinavian history and a symbol of medieval Christian influence in the region.

This naming also ties into the castle’s role in regional defense and its historical significance during the time it was built.

A Fortress Born from Conflict

Olavinlinna’s story begins in 1475, during a period of political upheaval following Ivan III’s conquest of the Novgorod Republic.

Erik Axelsson Tott, a Swedish nobleman and military leader, saw an opportunity to fortify Sweden’s eastern border against the expanding Russian Empire.

The military leader chose a strategic site in Savonia, where the waters naturally offered a defense to lay the foundation for what would become a symbol of Swedish strength.

A Cutting-Edge Fortress

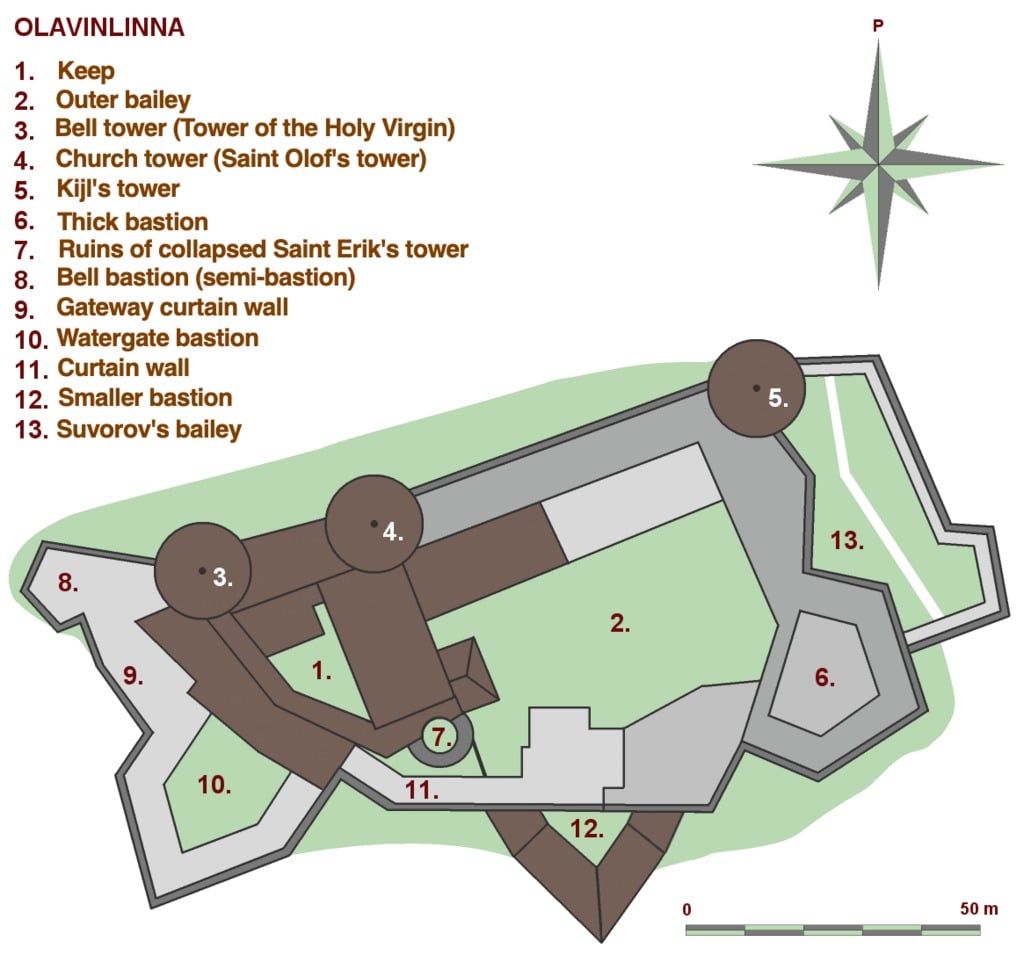

At its heart, Olavinlinna was a cutting-edge fortress for its time.

The castle’s three original towers, completed by 1485, were among the first in Sweden to be designed specifically to withstand cannon fire—a necessity in an era when warfare was rapidly evolving.

These thick, circular towers, paired with strong curtain walls, made Olavinlinna a formidable stronghold.

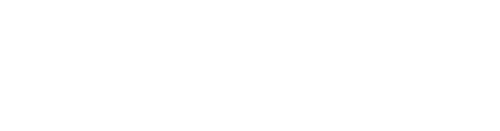

The castle is roughly shaped like a truncated rhomboid, with the keep on the western side and the curtain walls and outer bailey to the east.

Over the centuries, Olavinlinna Castle has seen many changes.

St. Erik’s Tower, one of the keep’s original towers, collapsed due to a weak foundation.

In the 18th century, another tower in the bailey, known as the Thick Tower, was destroyed in an explosion.

A bastion was built on the site of the ruined tower.

Later in the 18th century, the castle was transformed into a Vaubanesque fort, with the addition of bastions to strengthen its defenses.

Olavinlinna Has Seen Its Fair Share Of Conflict

Throughout the First and Second Russian-Swedish wars, the castle withstood numerous sieges.

Despite these attacks, it was never taken by force.

However, the garrison surrendered to Russian forces twice—once in 1714 and again in 1743.

The latter surrender led to the Treaty of Åbo, where Olavinlinna and the surrounding region were ceded to Russia, marking the beginning of a new chapter in the castle’s history.

During its time under Russian control, the renowned military leader Alexander Suvorov inspected the fortress’s rearmament.

The castle was modernized with the addition of bastions, transforming it into a more contemporary fortress.

Unfortunately, several fires in the 19th century destroyed much of the castle’s interior and original furnishings.

From Fortress to Festival Stage

Today, Olavinlinna Castle is no longer a site of conflict, but rather a famous tourist destination with several exhibitions, including the Castle Museum and the Orthodox Museum.

The Castle Museum displays artifacts found in or related to Olavinlinna.

The Orthodox Museum showcases icons and religious artifacts from both Finland and Russia.

Since 1912, it has been the stunning backdrop for the Savonlinna Opera Festival, an annual event that draws music lovers from around the world.

Olavinlinna Has Also Left Its Mark On Popular Culture

Fans of the Adventures of Tintin might recognize the castle as the inspiration for Kropow Castle in “King Ottokar’s Sceptre,” one of the famous graphic novels by Hergé.

Architecture

Courtyard

After arriving at the castle via the Bridge and entering through the Watergate Bastion, visitors will walk into the Courtyard within the Inner Bailey.

This small courtyard is surrounded by the three towering structures and the curtain wall that connects them.

The northern wing used to be the living quarters, the eastern wing was set aside for celebrations and household activities, and the southern wing housed the castle’s kitchen, which has since been demolished.

The Central Hall

The Central Hall is a part of the Castle Households. It spans two floors and was where people lived.

Castle workers were paid with food and housing, and they accessed these living quarters via a central spiral staircase since the northern wall was solid for defense.

On the first floor, the men-at-arms and servants would have lived.

The second floor was reserved for the bailiff’s residential rooms.

The large statue of St. Olaf, the castle’s patron saint, was only added after 1911.

The Bell Tower

The Bell Tower, also known as St. Virgin’s Tower, was built on the highest point of the island for the best defensive visibility.

On the first floor of this tower, there was a Storeroom used for storing food and clothing.

This room was protected by a 3-meter-thick stone wall.

The items kept here were collected as taxes from nearby regions or produced on the crown estate.

The items kept here were collected as taxes from nearby regions or produced on the crown estate.

They included dried grain, salted and smoked fish and meat, metal dishes, furs, hides, and textiles.

A housekeeper managed the clothing, and a scribe kept track of the tax records.

At the very top was the Lookout Storey, where visitors could see from the Outer Wall of the Courtyard.

Inside the Bell Tower is the Medieval Armory.

This was a key defense area within the inner bailey.

It’s where they stored weapons like longbows, crossbows, harquebuses, gun barrels, and various projectiles.

The Church Tower

Next to the Bell Tower was the Church Tower, or St. Olaf’s Tower.

This tower was likely part of the castle’s original fortifications.

The construction technique and masonry suggest it was built by 16 foreign masons in the 1470s.

The stone used was sourced locally, the mortar was made from sand from Kuhaslmi, and the lime was produced in a nearby lime kiln.

A narrow hallway

Next, visitors will walk through a narrow hallway to reach the Outer Wall of the Courtyard.

This spot would have had soldiers stationed with longbows and crossbows.

The longbows were made from flexible wood and had strings made from plant fibers or animal tendons.

They could shoot arrows up to 120 meters and fire about six arrows per minute.

On the other hand, crossbows were slower, shooting just one arrow per minute, but their arrows could reach up to 360 meters.

Here are some pictures of the castle’s interior: