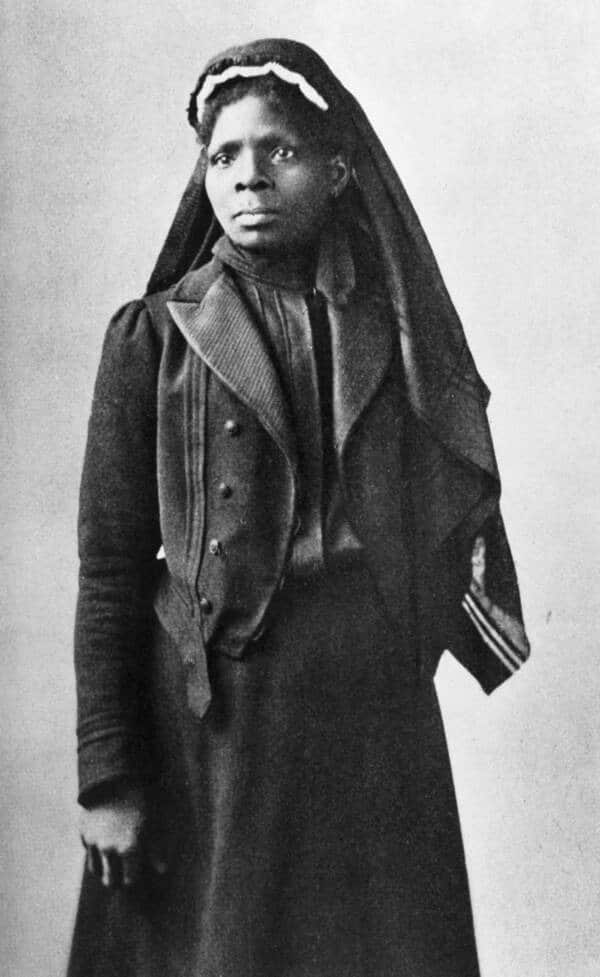

Meet Susie King Taylor: The First Black Army Nurse Who Also Taught Union Soldiers

Have you heard of Susie King Taylor? Even if you’ve heard her name, you might not know the full extent of her accomplishments.

In an era when women had few rights, and African Americans had none, what she did is truly extraordinary. She became both a teacher and a nurse despite the severe risks associated with literacy for Black people.

How Susie King Taylor secretly educated herself

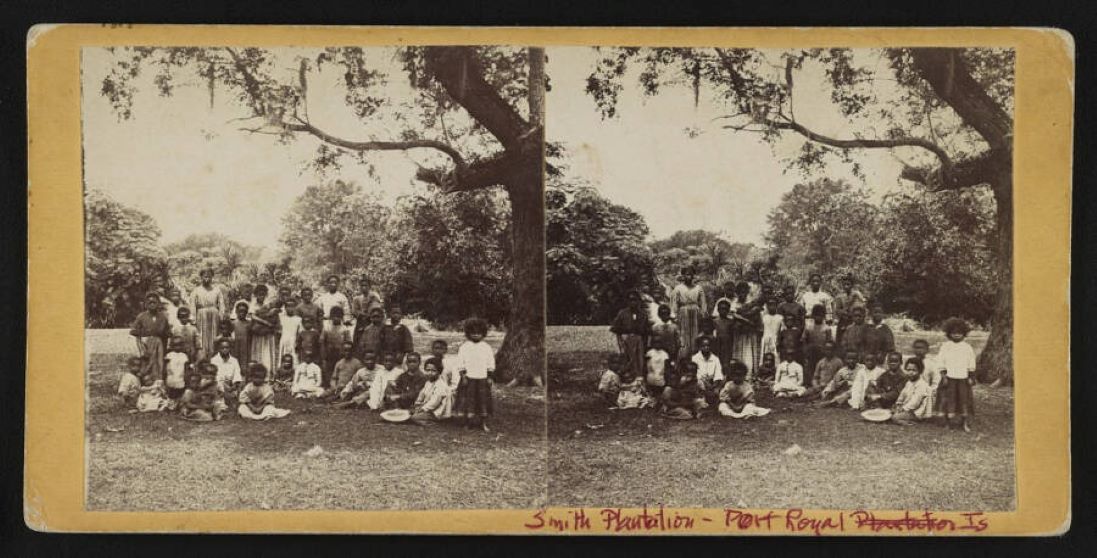

Susie King Taylor, born Susan Ann Baker on August 6, 1848, started life as a slave on the Great Plantation in Liberty County, Georgia.

At seven, her grandmother, Dolly, took her to Savannah, where she arranged for Taylor to receive a secret education despite the immense risks.

Educating enslaved children was illegal in Georgia, but Dolly was determined. Taylor and her brother attended clandestine classes taught by free Black women like Mrs. Woodhouse and Mrs. Mathilda Beasley.

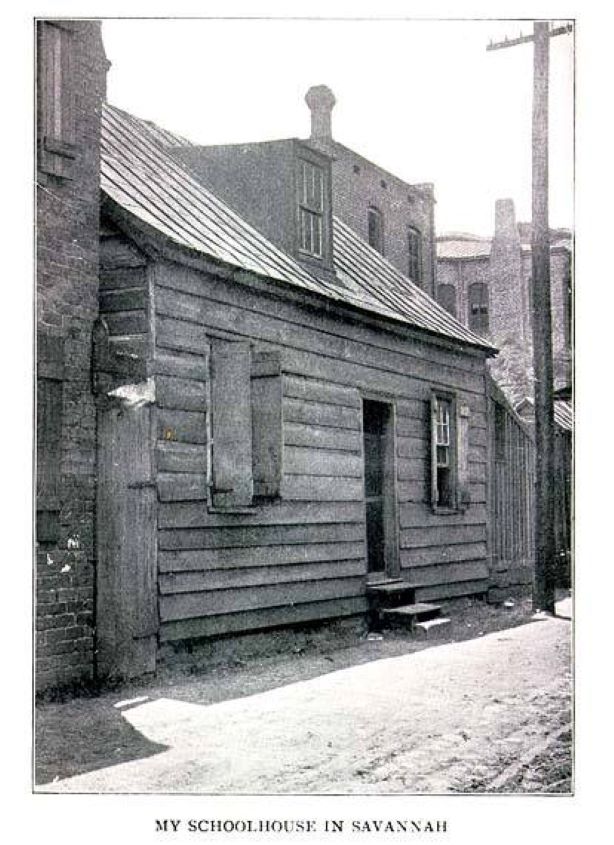

Mrs. Woodhouse’s school was discreet; children arrived one by one, books hidden to avoid detection. For two years, Taylor thrived in this underground education system before continuing her studies with Mrs. Beasley, Savannah’s first Black nun.

Dolly’s efforts didn’t stop there; Taylor’s education continued with lessons from her friend Katie O’Connor, a convent student, and later from James Blouis, the landlord’s son.

Taylor’s literacy became a tool of empowerment. As a child, she wrote passes that protected Black people from arrest after curfew.

This ability to read and write provided safety and a semblance of autonomy, foreshadowing her future role in supporting the Union during the Civil War.

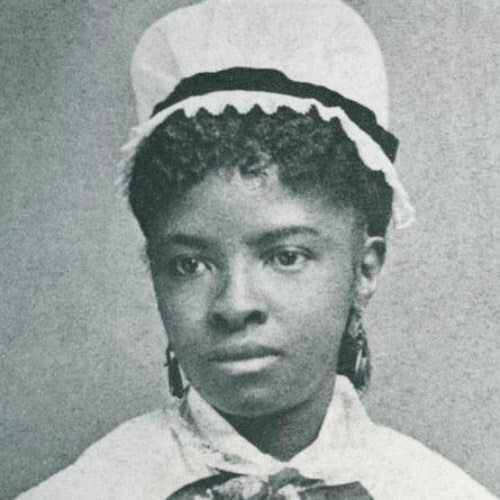

Taylor became an invaluable nurse during the Civil War

As the Civil War erupted in April 1861, Taylor and her family fled to St. Simon’s Island aboard a Union ship. There, she impressed Lieutenant Pendleton G. Watmough with her intellect, securing a job at the Union base.

“He was surprised by my accomplishments,” she later wrote in her memoir, reflecting on how unusual it was for a Black person in the South to be literate.

At just 14, Taylor taught up to 40 children by day and many adults by night. When St. Simon’s Island was evacuated, she moved to Beaufort, South Carolina, joining Camp Saxton.

There, she cared for the all-Black 1st South Carolina Volunteers Infantry Regiment, which later became the 33rd U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment.

While serving with the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, Susie King Taylor formed deep bonds with her fellow soldiers and officers who respected her dedication despite racial barriers.

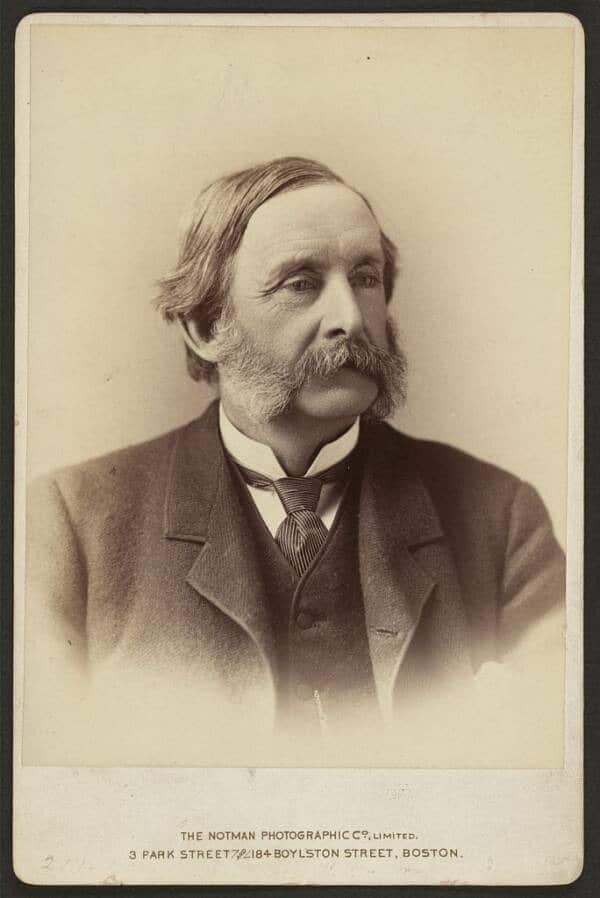

The regiment, formed in November 1862 by Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Lieutenant Colonel Charles T. Trowbridge, became her second family.

Higginson was a dedicated abolitionist, and Trowbridge was well-regarded by his all-Black regiment. Among the soldiers was Sergeant Edward King, whom Taylor married and accompanied during his tours.

She became an invaluable nurse, fearlessly tending to soldiers afflicted with diseases like malaria, measles, cholera, and smallpox.

“I was not in the least bit afraid of the smallpox,” she wrote. “I had been vaccinated, and I drank sassafras tea constantly, which kept my blood purged and prevented me from contracting this dreaded scourge.”

In addition to nursing, Taylor taught Company E soldiers how to read and write. She even learned to shoot a musket and maintain the army’s weaponry, ensuring the cartridges in the Army’s guns stayed dry.

Despite her tireless work, she was officially designated a laundress, a title that denied her the pay and pension given to nurses. Trowbridge later apologized for this “technicality” in her title.

In March 1863, when the Volunteers were ordered to march to Florida, Taylor steadfastly followed to continue her invaluable support.

She served alongside the Union Army

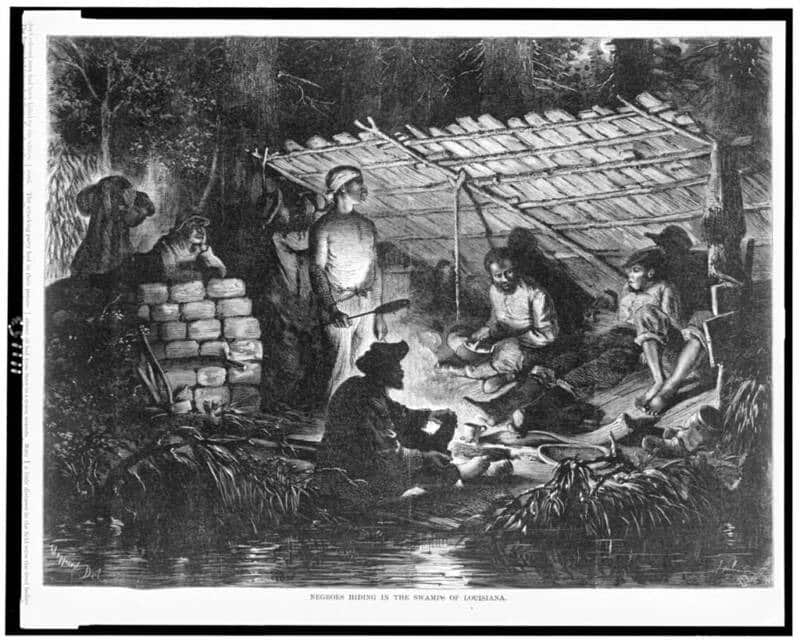

As the brigade marched into Florida, they faced a dangerous deception. Confederate soldiers had blackened their faces to blend in, causing a momentary confusion among the Volunteers.

Taylor recalled, “They were hiding behind a house about a mile or so away, their faces blackened to disguise themselves as negroes… our boys… halted a second, saying, ‘They are black men!’”

This ruse led to several injuries and deaths before the regiment retreated to South Carolina.

These harrowing experiences deeply affected Taylor. She began visiting hospitals like Beaufort’s “Contraband Hospital,” dedicated to fugitive slaves and wounded Black soldiers.

“It seems strange how our aversion to seeing suffering is overcome in war,” she wrote.

During her hospital visits, Taylor met notable figures like Clara Barton, the founder of the Red Cross. As the war dragged on, she witnessed violent clashes and the horrors of battle, such as at Fort Gregg on Morris Island.

“Outside of the fort were many skulls lying about… I had become accustomed to worse things,” she recounted, illustrating the toll the war took on her.

Before the war ended in 1865, Taylor survived numerous dangers, including nearly capsizing on a ship and evading bushwhackers. She also witnessed her men extinguish fires in Charleston amidst hostility from white civilians.

She continued to teach freed Black Americans

Nearly a year after the war, Colonel Trowbridge praised his troops, saying their “valor and heroism has won for your race a name which will live as long as the undying pages of history shall endure.”

However, the end of the Civil War didn’t end racism. During the Reconstruction Era, newly freed Black Americans faced immense challenges.

Susie King Taylor vividly described these struggles, writing, “In this ‘land of the free’ we are burned, tortured, and denied a fair trial, murdered for any imaginary wrong.”

Taylor herself faced many difficulties after the war. Her husband, a skilled carpenter, struggled to find stable work and died in a tragic accident in 1866.

As a single mother, Taylor wanted to continue teaching but found no opportunities. She briefly opened a school but had to close it and find work as a domestic worker.

Nonetheless, Taylor remained active, organizing Corps 67 of the Women’s Relief Corps to support Union Army veterans. This work eventually took her to Boston, where she found a supportive community.

Her memoir, written after caring for her dying son in 1902, was published that same year.

Susie King Taylor died in 1912, leaving behind a legacy of courage and compassion. She remains a symbol of strength and resilience, an unspoken hero of the American Civil War.