Mary Armstrong’s Remarkable Journey To Freedom Will Amaze You

One of the most significant moments in American history occurred on January 1, 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. This executive order declared freedom for all enslaved individuals in Confederate-held territories.

While it didn’t immediately liberate all slaves, applying only to Confederate states not under Union control, it nonetheless represented a pivotal step in the fight against slavery during the Civil War.

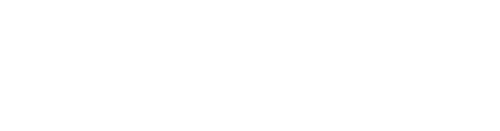

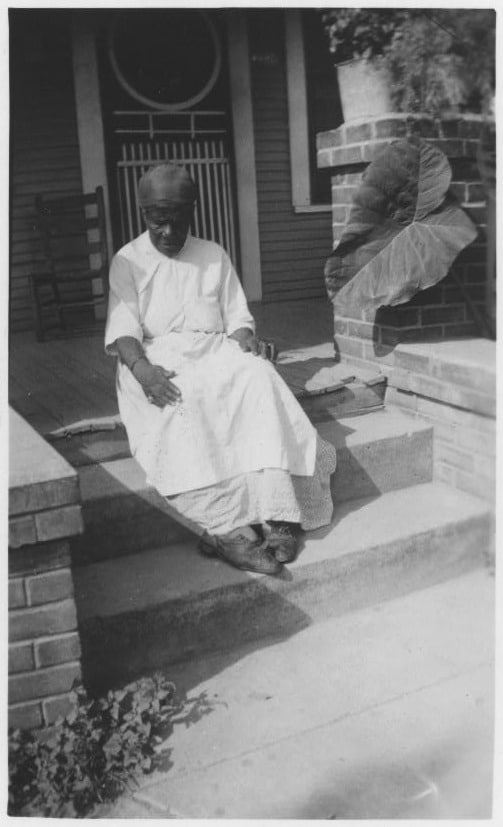

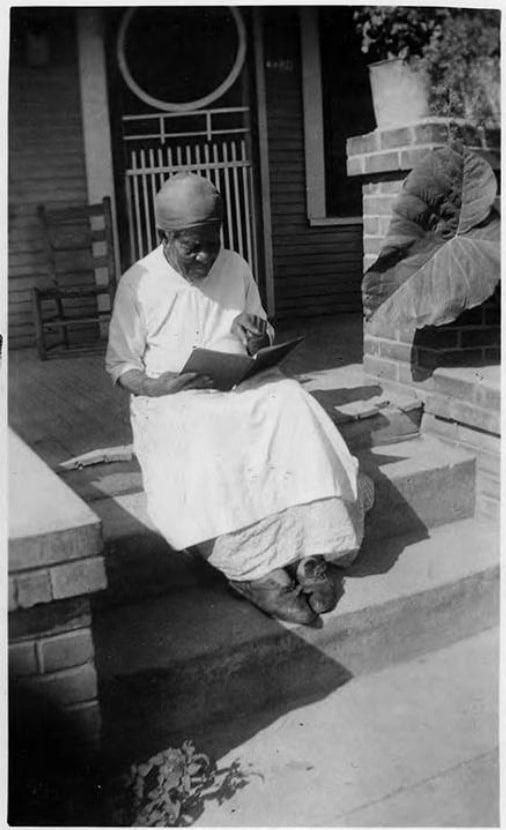

Amid the many captivating stories of freed African-American slaves, Mary’s narrative deserved more attention. Mary Armstrong lived in slavery for many years. Her story told us about the hardships she faced and her resilient spirit.

Her hellish life at Cleveland’s plantation

Mary Armstrong was born into slavery on June 2, 1847, on a farm near St. Louis, Missouri, to Sam Adams and Silby. Mary described her owners, William and Polly Cleveland, as “the meanest two white folks who ever lived.”

William Cleveland was notorious for his brutality, chaining slaves to whip them and rubbing salt and pepper into their wounds, claiming to “season him up.” When selling a slave, he would grease their mouths to make it look like they had been well-fed and healthy.

Polly Cleveland’s cruelty peaked when she brutally killed Mary’s 9-month-old sister. This act of violence left an indelible mark on Mary, a memory she carried for her entire life.

“She come and took the diaper offen my little sister and whipped till the blood jes’ ran — jes’ ’cause she cry like all babies do, and it kilt my sister,” said Mary Armstrong, August 8, 1937.

Cleveland often took out loans using his slaves as collateral. He would then sell these slaves in the South. When the lenders came to collect, Cleveland would claim the slaves had escaped, avoiding repayment.

Worse still, Cleveland sold men, women, and children separately, ignoring their family bonds. He didn’t care about keeping families together. Eventually, Mary’s parents were sold away from her as well.

Finding hope amidst hardship

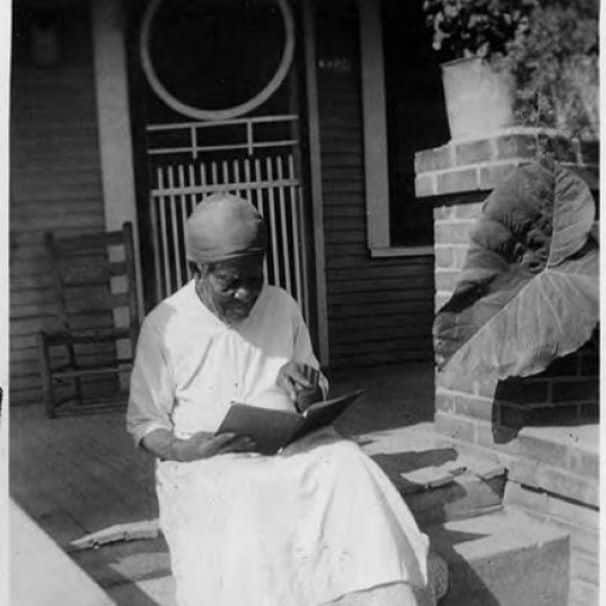

” A Midnight Race on the Mississippi”

Olivia Cleveland Adams was the daughter of William and Polly Cleveland. Unlike her cruel parents, Olivia was loving, kind, and adored by everyone, both black and white.

When Olivia married William Adams, a man with five farms and 500 enslaved persons, he bought Mary from Olivia’s parents for $2,500. Mary’s life improved significantly under their care.

Old Polly, however, still visited sometimes. She once tried to buy Mary back, but Olivia refused, saying, “I’d wade in blood as deep as Hell before I’d let you have Mary.” This showed how much Olivia cared for Mary.

One memorable incident happened when Mary was about ten years old. Polly tried to whip her again.

Mary recounted, “…one day old Polly devil comes to where Miss Olivia lives after she marries, and trys to give me a lick out in the yard, and I pick up a rock ‘boat as big as half your fist and hits her right in the eye and busted the eyeball, and tells her that’s for whipping my baby sister to death. You could hear her holler for five miles, but Miss Olivia, when I tell her, says, “Well, I guess mamma has larnt her lesson at last.’

Life with the Adams family was a turning point for Mary. She performed domestic duties, such as nursing infants and spinning thread, and even learned to dance, a skill she became quite proficient in.

Olivia and William genuinely cared for Mary, who affectionately referred to them as “pappy” and “mammy” in private. One memorable event was when William took Mary to watch a steamboat race, a rare and exciting outing for her.

Emancipation and journey to freedom

In 1863, William Adams emancipated his enslaved persons following President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. He provided Mary with documents declaring her freedom and warned her about the dangers that still existed. Armstrong was set free at about 17.

Mr. Will carefully advised her, ‘Fore you gets off the block, jos’ pull out the papers, but jes’ hold em up to let folks see and don’t let em out of your hands, and when they sees them they has to let you alone.’

“Miss Olivia cry and carry on and say be careful of myself ’cause it shot rough in Texas. She give me a big basket what had so much to eat in it I couldn’t hardly heft it and ‘nother with clothes in it.”

Armed with her documents, Mary set out for Houston, Texas. Despite being captured by traders upon arrival, she secured her release with these papers. A state official, respectful of the law, inspected her papers and declared, “This gal is free and has papers,” setting her loose.

Mary stayed with Charley Crosby, a decent man who allowed her to work and earn her way to a refugee camp for the formerly enslaved. She remained with Crosby until the end of the Civil War, then set out to find her mother.

Reunion with mother and later life

Mary eventually reunited with her mother, Silby, in Wharton County. She fondly remembered the joyous reunion with her mother at the refugee camp, saying, “Law me, talk ’bout cryin’ and singin’ and cryin’ some more. We sure done it.”

In 1871, she married a guy named John Armstrong, and the family moved to Houston.

There, Mary worked as a nurse during the Yellow Fever pandemic, showcasing her compassion and dedication to helping others. Mary trained as a nurse and saved numerous lives during the outbreak in the 1870s.

Mary Armstrong lived a long life, passing away in 1937 at the age of 91.