Lindbergh Baby Kidnapping Mystery: Did Bruno Hauptmann Actually Do It?

On the morning of September 15, 1934, a dark blue Dodge sedan pulled up to a Warner-Quinlan service station on Lexington Avenue in upper Manhattan. The car driver requested five gallons of ethyl gasoline, and the station manager, Walter Lyle, filled the car with 5 gallons of gasoline and said, “That’s 98 cents.”

The driver handed Lyle a $10 bill from a white envelope. Lyle noticed something unusual about the bill. So, he said to the driver, “You don’t see many of these anymore.” Can you believe it? It was a gold certificate, which had been out of circulation for over a year due to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s decision to take the country off the gold standard. This action was a response to people hoarding gold during the Great Depression.

The driver casually mentioned that he had about a hundred of these gold certificates left. Lyle, remembering a company warning about potential counterfeit gold certificates, took note of the car’s license plate number—4U13-41—by writing it on the margin of the bill.

Three days later, when the service station deposited the money, a teller at the Harlem branch of the Corn Exchange Bank noticed the unusual bill. Checking its serial number, the teller discovered it was part of the ransom paid in the infamous kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh Jr., the 20-month-old son of the famous aviator, Charles Lindbergh. The bank immediately notified federal investigators.

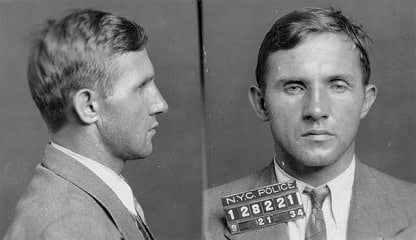

The Investigation of Bruno Hauptmann

The investigators traced the license plate number to Bruno Richard Hauptmann, a German immigrant carpenter living in the Bronx.

The following morning, police and federal agents surveilled Hauptmann as he left his apartment and drove away. Confirming the license plate, they pulled him over and found a $20 gold certificate from the ransom money in his billfold. Hauptmann was arrested, finally breaking a case that had consumed thousands of man-hours and led to many false leads.

The police searched Hauptmann’s garage and discovered $13,750 of the ransom money hidden in various places, including an oil can, a package inside a wall, and an earthenware pickling jar buried beneath the garage floor.

Despite the overwhelming evidence, Hauptmann claimed he had no connection to the crime. He stated that he had received the money from a deceased business partner and was hoarding gold certificates to protect himself from inflation, drawing from his experience in post-World War I Germany.

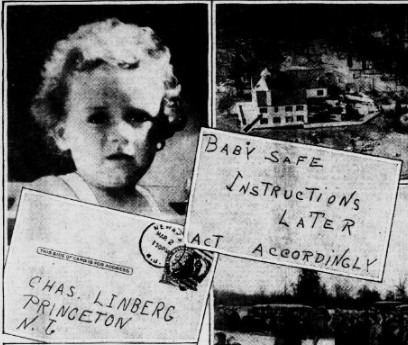

The kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh Jr.

The kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh Jr. occurred on the night of March 1, 1932. The baby was taken from his crib in the Lindberghs’ New Jersey estate, leaving behind only muddy footprints, a homemade ladder, and a ransom note.

Despite paying the ransom a month later, the baby was not returned. Tragically, the child’s decomposed body was found six weeks later near the Lindbergh estate, with an autopsy revealing a fatal skull fracture, likely from being dropped during the kidnapping.

Bruno Hauptmann’s Conviction

Hauptmann’s trial in 1935 was sensational, culminating in his conviction for kidnapping and murder. He was executed the following year. Prosecutors presented strong evidence, including a homemade ladder matched to wood from Hauptmann’s attic and handwriting analysis linking him to the ransom notes.

However, Hauptmann maintained his innocence until his death, leading to ongoing debates about his guilt. Some believe he acted alone, while others suggest he was part of a broader conspiracy, with theories even implicating Lindbergh himself.

Despite the conviction, the Lindbergh baby kidnapping remains one of the most debated crimes in American history, leaving lingering questions and various theories about the true nature of the crime.