Life In 1930s New York During The Great Depression

Old photographs serve as windows into the past, telling us the stories of our past. Each image captures a slice of time, often reflecting the struggles, joys, and resilience of people from different eras.

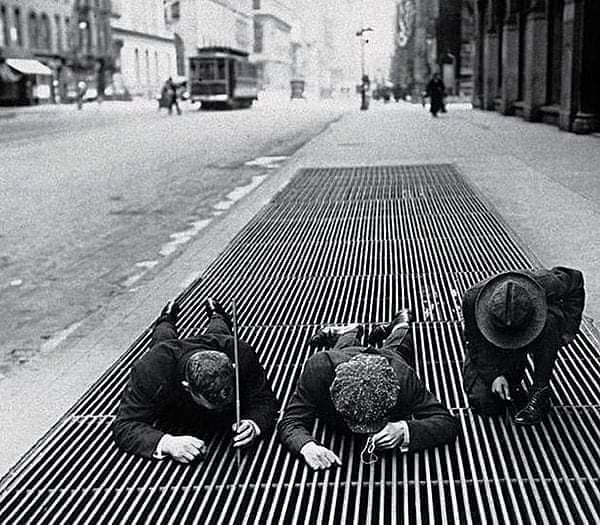

A photograph featuring children fishing for dropped change in street grates in New York City, makes many people curious for their first time. The kids, dressed in typical clothing of the 1930s, exhibit determination as they look for coins that may have fallen.

This black-and-white image reflects the struggles of the Great Depression, highlighting how even small amounts of money were precious during this difficult time.

State of affairs

As the 1920s progressed, the economy boomed that led to a period of unchecked excitement and speculation. Stock prices soared to unrealistic heights, with many investors buying on margin—borrowing money to purchase stocks. Banks were quick to issue loans without proper caution, and factories produced goods at an alarming rate, creating a significant surplus.

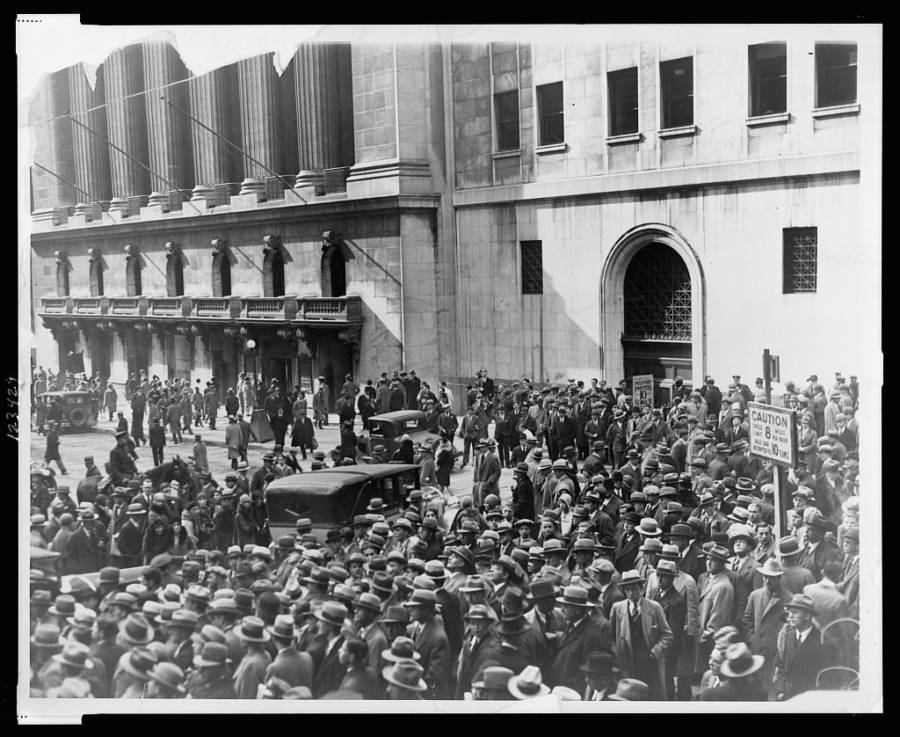

This bubble burst on Tuesday, October 29, 1929, a day now known as Black Tuesday. It marks the beginning of the Great Depression in New York City.

Following a chaotic week where stock prices dropped, a wave of panic swept through investors, prompting many to sell off their shares. Black Tuesday saw the market lose an astonishing $14 billion in just one day. The downward trend continued, with an additional loss of $30 billion the following week, culminating in a total decline of 89.2% from its peak in early September.

The consequences were severe. Bank failures and business closures were widespread. New York City emerged as the face of the Great Depression, recognized as the financial center where the crisis began and where its effects were most profoundly experienced.

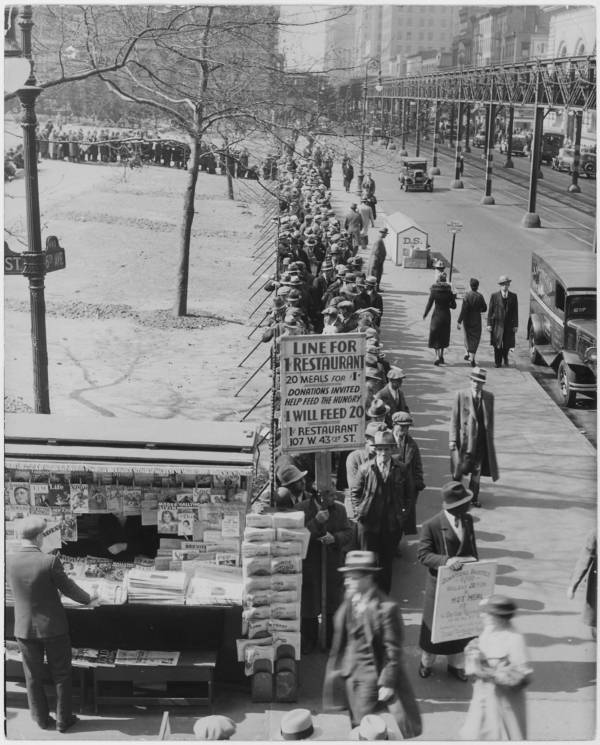

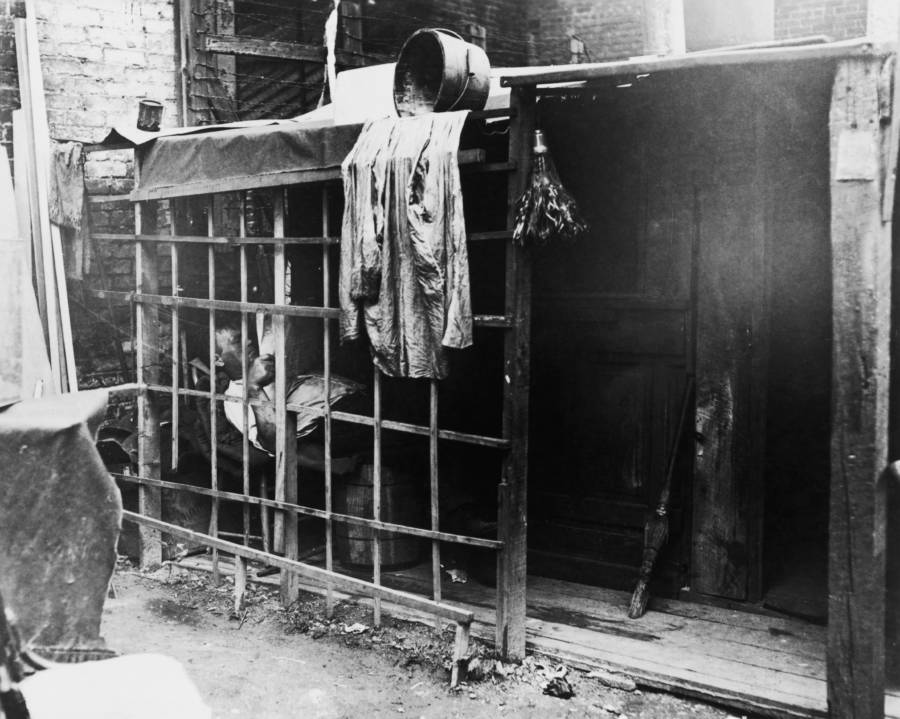

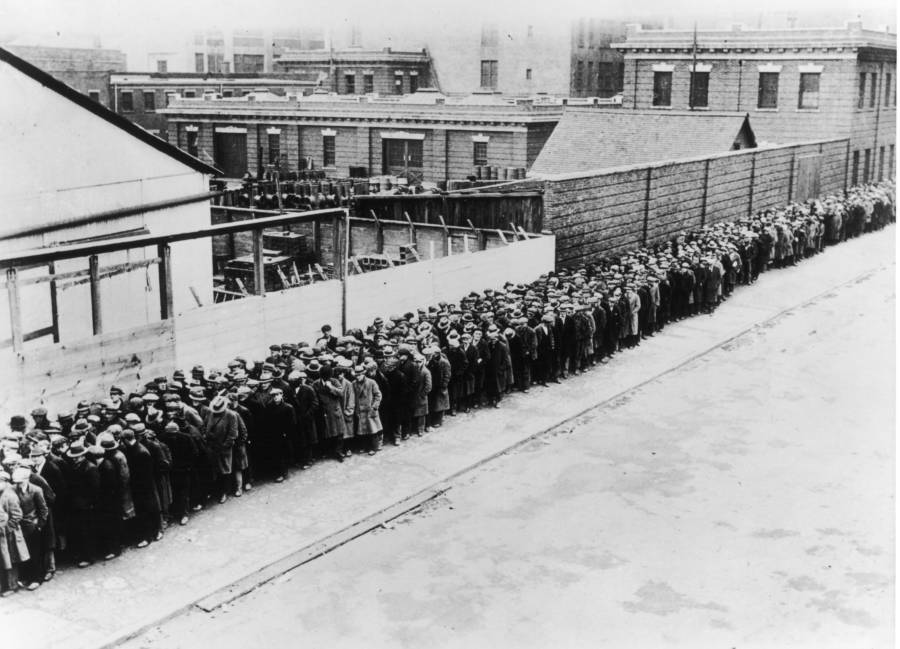

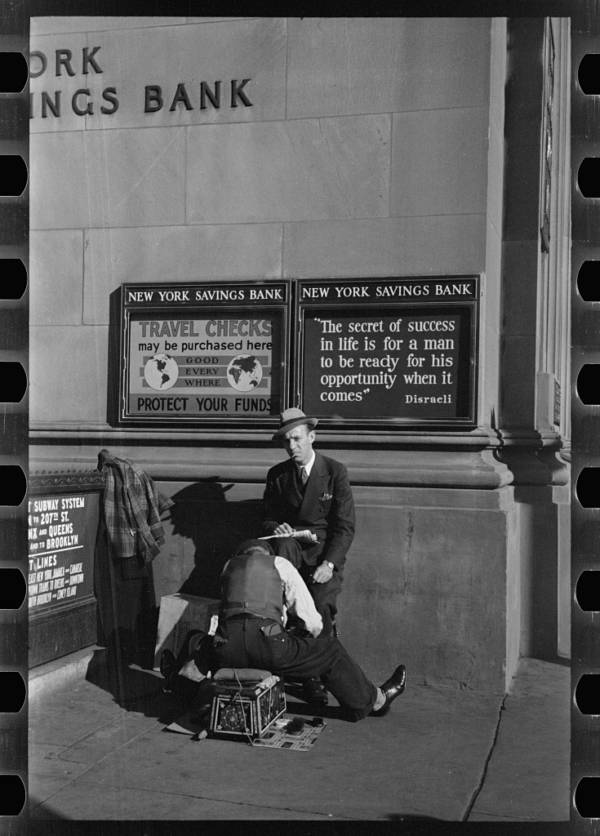

During the Great Depression, many New Yorkers faced severe hardships, especially losing their savings, jobs, and homes. By 1932, half of the city’s factories had closed, which led to nearly one-third of residents unemployed—much higher than the national average, and over half in Harlem alone. About 1.6 million people were on relief, while those who still had jobs often suffered significant pay cuts.

At the time, under Mayor Jimmy Walker, New York lacked coordinated municipal services to help the needy. There were no central traffic, highway, or public works departments; street cleaning was managed by individual boroughs; and there were multiple parks departments. Unemployment insurance was unavailable, and the Department of Public Welfare initially had no funds to assist those in need.

Like many cities, New York relied heavily on charitable organizations and almshouses to support the poor and hungry. However, these institutions openly admitted they could not meet the overwhelming demand for help during this crisis.

Some Short-lived Remedies

In October 1930, after receiving countless letters pleading for help from city officials and residents, Mayor Jimmy Walker took action by creating the Mayor’s Official Committee for Relief of the Unemployed and Needy.

By November, changes began to take effect, starting with the establishment of the City Employment Bureau, which helped job-seekers avoid paying fees to private agencies.

Efforts were also made to prevent the eviction of poor families struggling with rent, while the police conducted a citywide investigation to assess needs in all precincts.

Contributions from police and city employees boosted relief efforts, leading to an expansion of lodging facilities for the homeless. Additionally, a special Cabinet Committee was set up to handle essentials like food, clothing, and rent.

In its first eight months, the Committee raised $1.6 million, helping 11,000 families with direct aid and distributing 18,000 tons of food, including Kosher items, to nearly a million families. Night patrolmen often spent their shifts preparing these parcels. The funds also covered essentials like coal, shoes, and clothing.

Meanwhile, the Welfare Council provided over $12 million for relief efforts and emergency wages, all from voluntary donations. Private citizens contributed, while special events like exhibition sports games (such as Notre Dame vs. the New York Giants) and Broadway performances helped raise more funds.