How White Flight Significantly Changed Today’s American Cities

White flight, also called “white exodus,” is when white people move out of racially diverse cities to the suburbs. For instance, Chicago’s South Shore neighborhood was 96 percent white in 1950 but 96 percent Black by 1980.

This migration was influenced by the Great Migration, post-World War II economic prosperity, and racist legislation that restricted Black families from moving to the suburbs.

This trend transformed American neighborhoods and cities, with lasting impacts still felt today.

The impact of the Great Migration and 1930s housing laws

The dominoes that led to white flight arguably began to fall in the 1910s when Black Americans started to leave the South during the Great Migration. Between the 1910s and 1970s, six million Black Americans moved north, west, and to the Midwest.

As the Smithsonian Magazine reported, in the 1910s, 90% of Black Americans lived in the South; by the 1970s, 47% resided in the North and West.

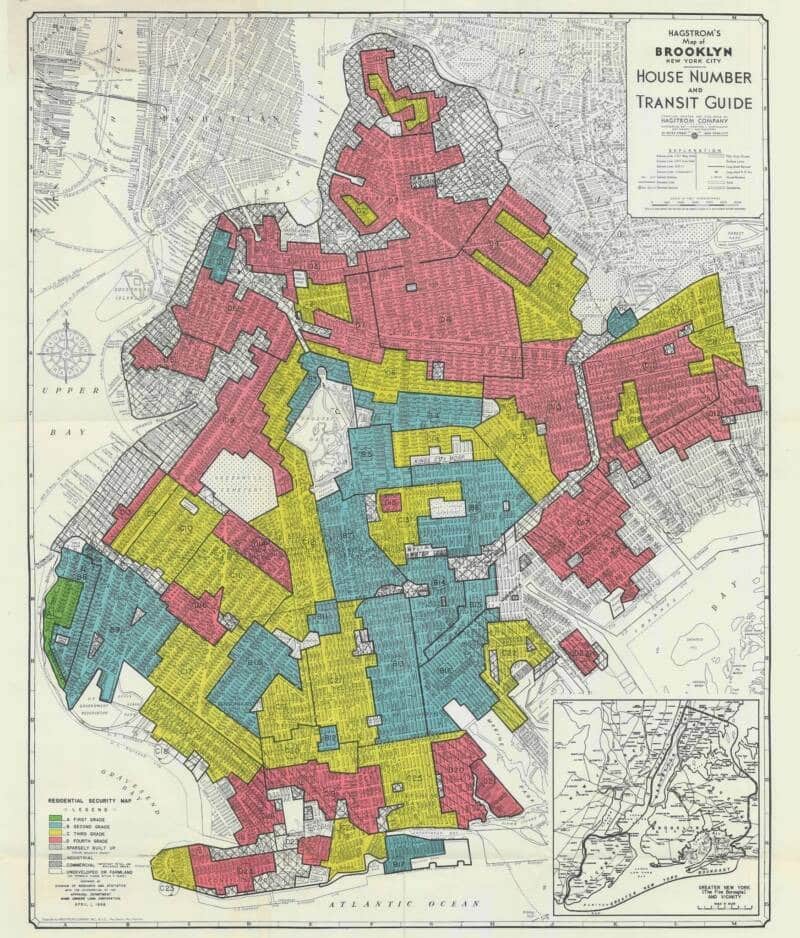

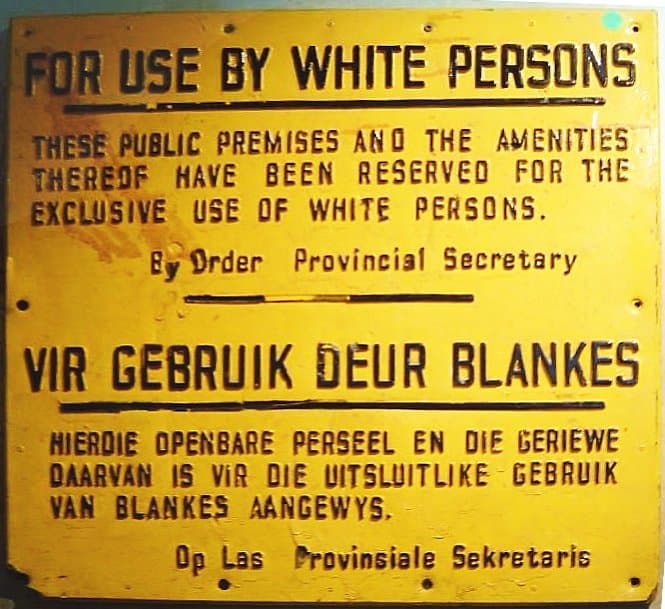

Meanwhile, 1930s federal policies laid the groundwork for housing discrimination. New Deal programs offered government-insured mortgages but excluded Black neighborhoods labeled as “high-risk.”

The Federal Housing Administration, established in 1934, refused to insure mortgages in Black neighborhoods, a policy known as “redlining.”

This even applied to integrated areas. If Black families moved in, nearby white homeowners couldn’t get mortgage assistance.

At the same time, the Federal Housing Administration subsidized subdivisions for white Americans, excluding Black families. Some houses had covenants that explicitly banned sales to non-white people.

This set the stage for white flight, which increased after World War II.

The rise of white flight post-wwII

Most historians believe white flight began in earnest in the 1940s. Princeton economics professor Leah Boustan noted that for every Black American who moved to the North and West between 1940 and 1970, two white people left.

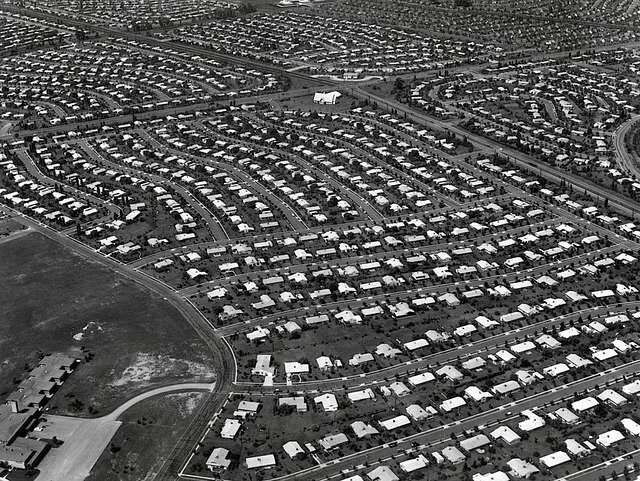

The post-World War II economic boom, especially the GI Bill, allowed many white families to buy suburban homes. Suburbs like Levittown, New York, expanded rapidly but were off-limits to Black families.

Fear of new Black neighbors prompted some white families to leave, a phenomenon exploited by realtors through “blockbusting.” This warned white homeowners that property values would drop as Black families moved in.

Meanwhile, Black families faced violent resistance when trying to move to the suburbs. Some suburbs were “sundown towns,” banning Black people after dark, and others didn’t allow them at all.

In 1951, a Black family trying to move to Cicero, Illinois, was driven out by a mob of 4,000 white protesters who set their property on fire.

The transformation of American urban centers

Between the 1940s and 1970s, many white Americans moved to the suburbs while Black Americans increasingly settled in urban areas.

Detroit’s Wayne County lost 26.6% of its white population by the 1970s, while Cleveland’s Cuyahoga County lost 20.1%, and Chicago’s Cook County lost 15.5%. Boston’s white population dropped from 759,000 in the 1950s to 394,000 by 1980, while its Black population tripled.

Michelle Obama, whose family moved to Chicago’s South Side, recalled, “As we moved in, white folks moved out.” White flight led to property value drops, tax increases, and worsening public services, creating a cycle of urban decay.

New York City’s Bronx lost one in five residents in the 1970s, leading to significant deterioration. Similarly, Gary, Indiana, faced deindustrialization and white flight.

Despite peaking in the 1970s, many experts believe white flight never truly ended. The suburbs expanded significantly during this period, with Levittown, New York, becoming a prime example.

Houses in Levittown were sold only to white veterans, excluding Black families, which further fueled white flight.

William J. Levitt, the developer behind Levittown, defended this as a business decision, saying, “If we sell one house to a Negro family, then 90 or 95 percent of our white customers will not buy into the community.”

Segregation in modern America

Though white flight officially lasted from the 1940s to the 1970s, segregation continues in different forms today. Many suburbs have become more diverse, but some white residents choose to live in exclusive, gated communities.

NIMBY (“not in my backyard”) movements often oppose low-income housing near wealthy neighborhoods. A study from the University of California, Berkeley, found that 81% of American cities were more segregated in 2019 than in 1990.

White flight is a key chapter in America’s complex story about race and segregation. This period saw both self-segregation, like in Levittown, and forced segregation, such as the violent exclusion of a Black family from Cicero, Illinois.