How Were The Dry Days Of The Prohibition Era?

Described by American President Herbert Hoover as “a great social and economic experiment,” Prohibition was a nationwide ban on the manufacture, transportation, and sale of alcohol across the United States for 13 years.

Prohibition briefly cut down on alcohol consumption and brought about some health benefits. However, it also led to unintended consequences, most notably the rise of organized crime.

Gangsters like Al Capone and Bugs Moran capitalized on the lucrative bootlegging business, turning illegal alcohol production and distribution into a thriving underground industry.

The start of America’s dry spell

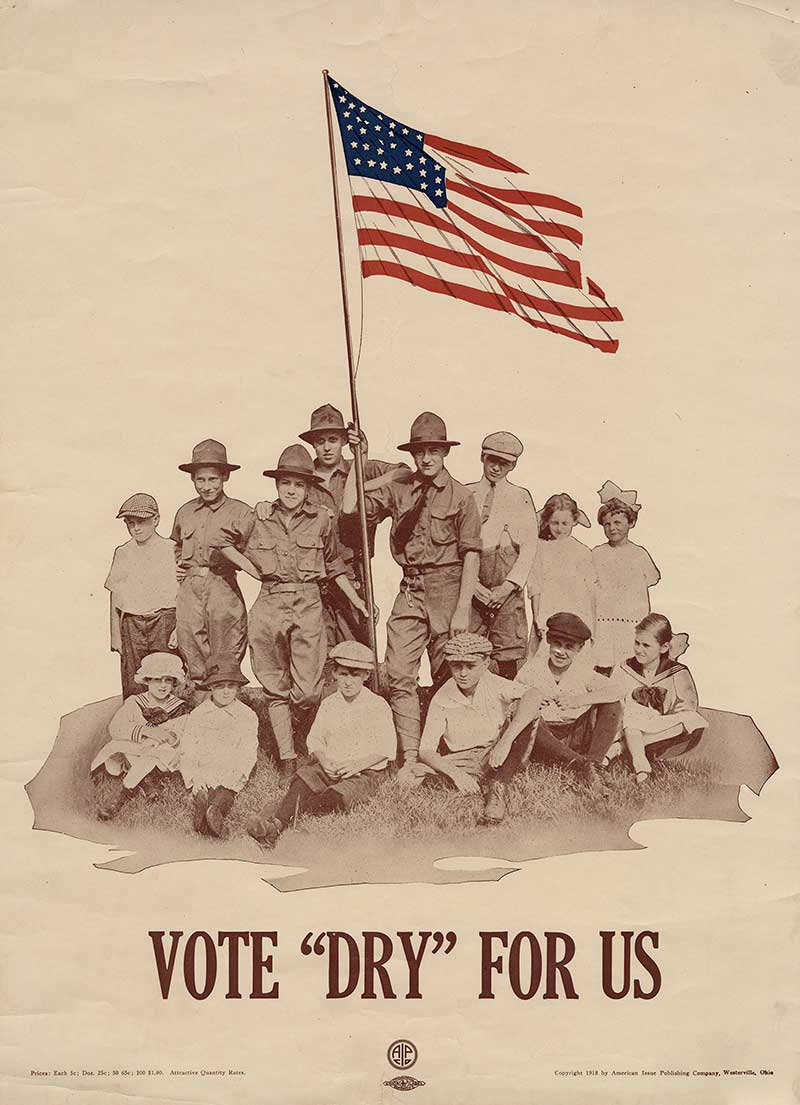

Prohibition began primarily as a religious initiative in the early 19th century. The state of Maine led the way by passing the first state prohibition law in 1846, and the Prohibition Party was established in 1869.

By the 1880s and 1890s, social reformers viewed alcohol as the root of many social problems like poverty, industrial accidents, and family break-ups. Others linked alcohol to urban immigrant ghettos, criminality, and political corruption.

Powerful groups such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), formed in 1874, and the Anti-Saloon League (ASL), founded in 1893, became key crusaders for prohibition. By 1916, 26 of the 48 states had passed prohibition laws.

America’s entry into World War I in 1917 further bolstered the movement, as prohibition was tied to grain conservation and aimed at German-American brewers.

The 18th Amendment, prohibiting the manufacture, sale, or transportation of alcohol, was adopted by Congress in December 1917 and ratified by the necessary states by January 1919.

The National Prohibition Act, or Volstead Act, implemented the amendment, defining ‘intoxicating liquor’ as any beverage containing more than one-half of one percent alcohol by volume.

Yet, prohibition allowed exceptions for medicinal, sacramental, or industrial purposes and lasted until its repeal in 1933.

Enforcement and effectiveness of Prohibition

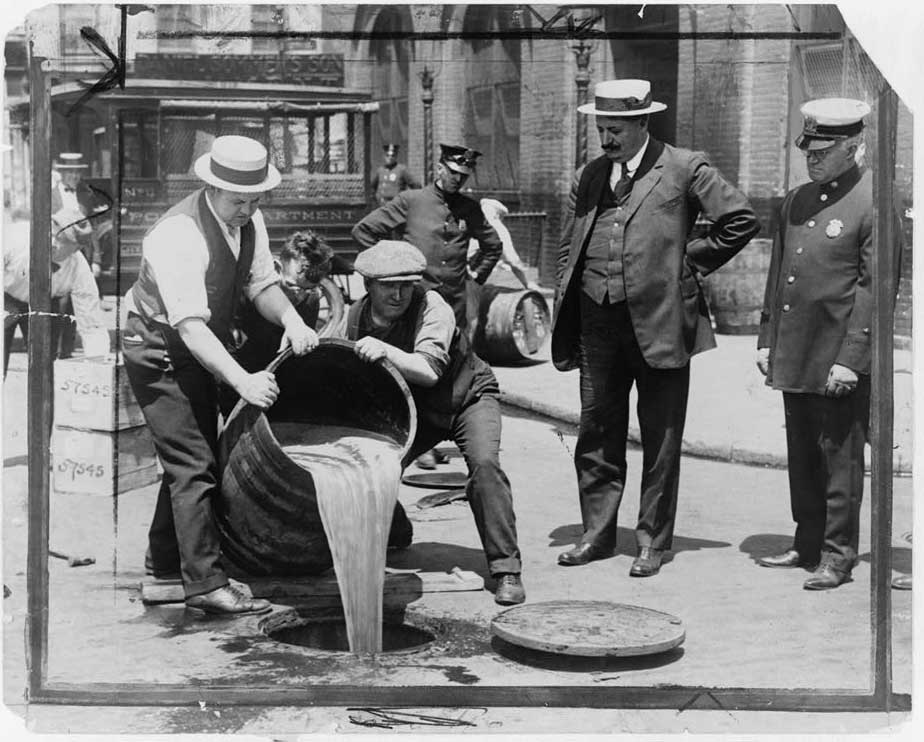

Prohibition faced significant challenges in enforcement throughout the 1920s. Initially, the task was assigned to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), but it was soon transferred to the Justice Department and the Bureau of Prohibition.

Despite the law’s passage, enforcement proved difficult and inconsistent.

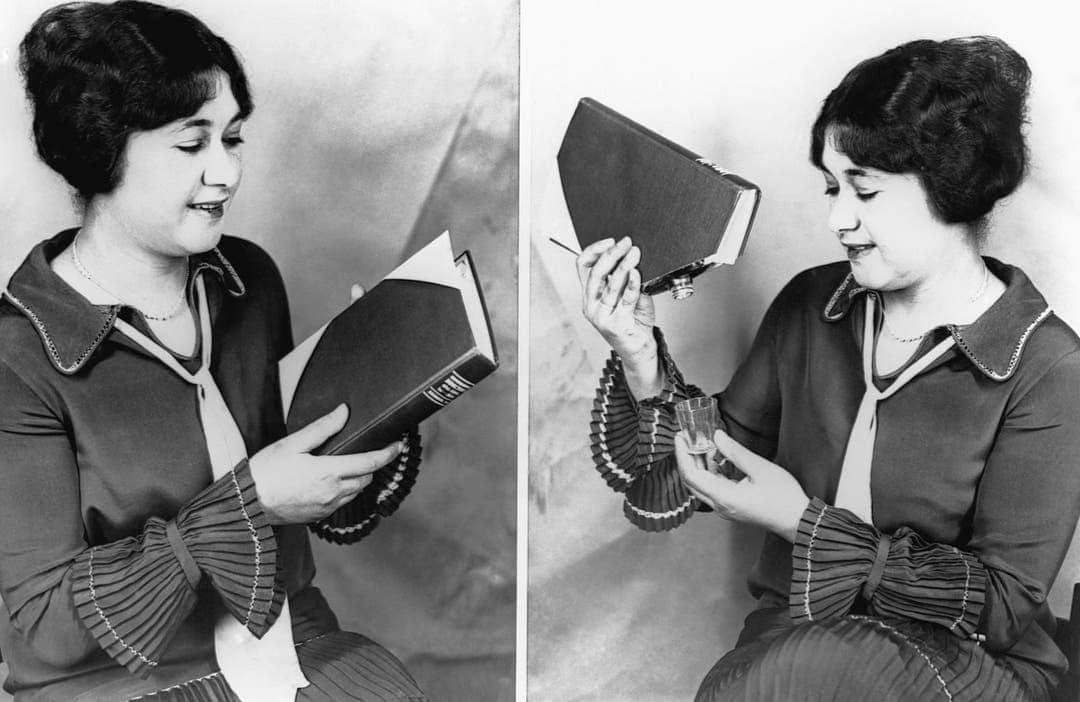

The enforcement issues began with legal loopholes. Doctors could prescribe alcohol for ‘medicinal’ use, and many exploited this to obtain and distribute it. The sale of ‘sacramental wine’ also surged.

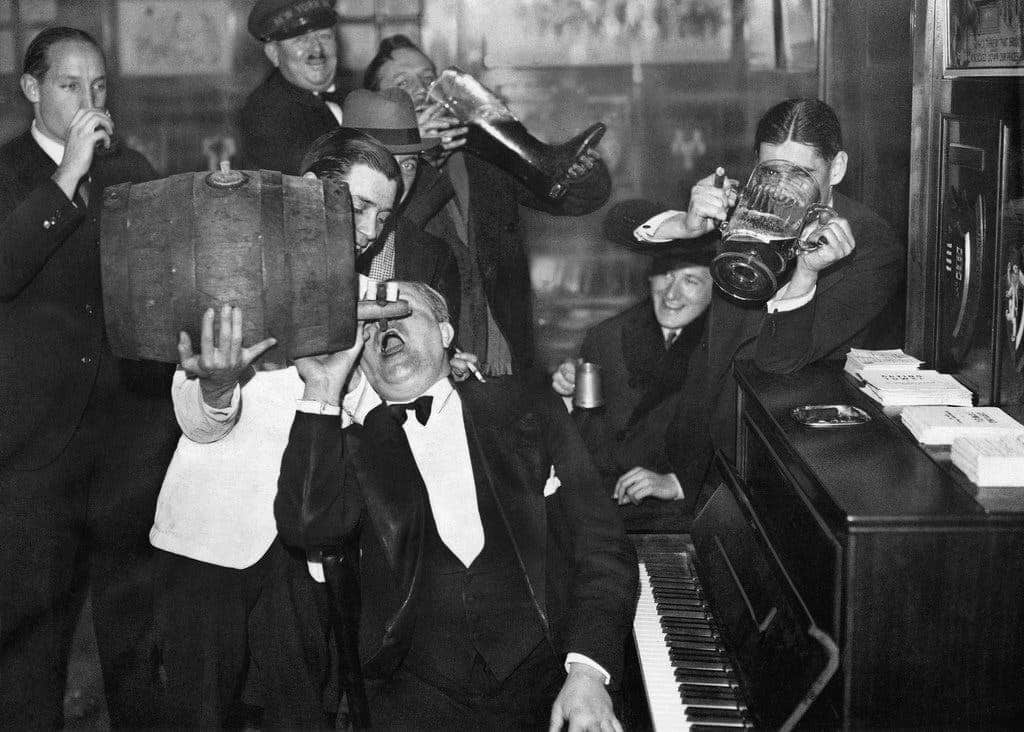

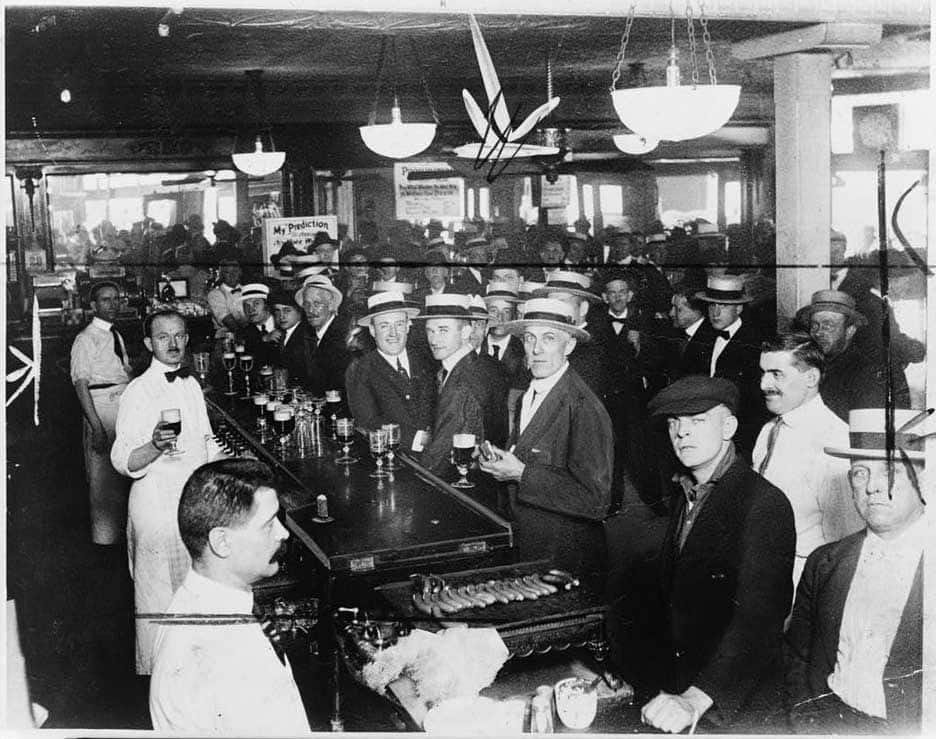

Although private possession and consumption of alcohol were not illegal, the high demand led to the rise of illegal establishments known as ‘speakeasies’ or ‘blind pigs,’ with estimates suggesting around 200,000 by the end of the decade.

People also started brewing their own illicit alcohol, such as ‘moonshine’ and ‘bathtub gin.’

The Bureau of Prohibition, staffed by about 3,000 agents, struggled to control the illegal alcohol trade. They had to monitor both the smuggling at borders and the domestic production of illicit alcohol.

Corruption was widespread; in Chicago, it was claimed that half the police force was on the payroll of gangsters, and in New York, only 17 convictions came from 7,000 arrests.

Enforcement was tougher in rural areas, where most people supported Prohibition, but in urban areas, the law was applied more loosely.

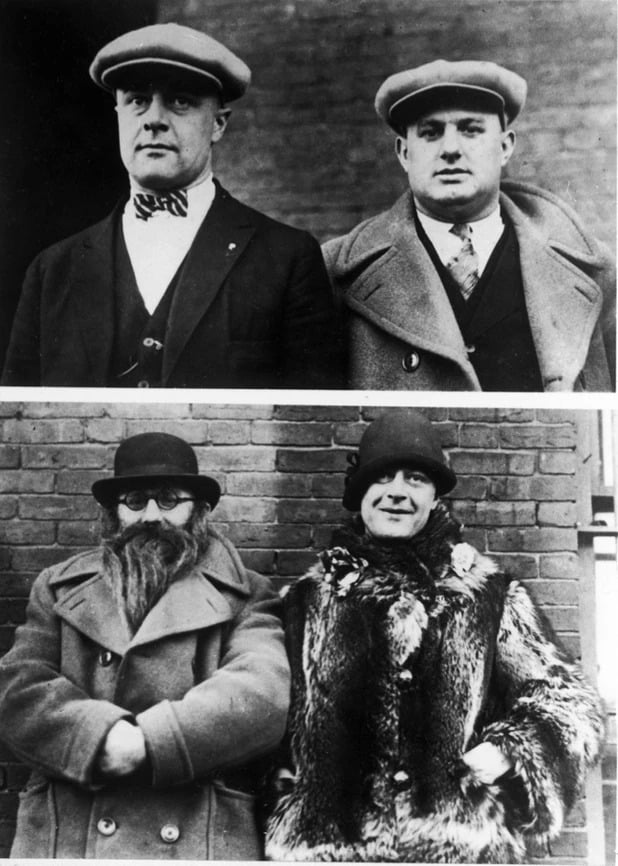

Despite these difficulties, some agents gained fame for their efforts. Izzy Einstein and Moe Smith, known for their inventive disguises, made nearly 5,000 arrests from 1920 to 1925.

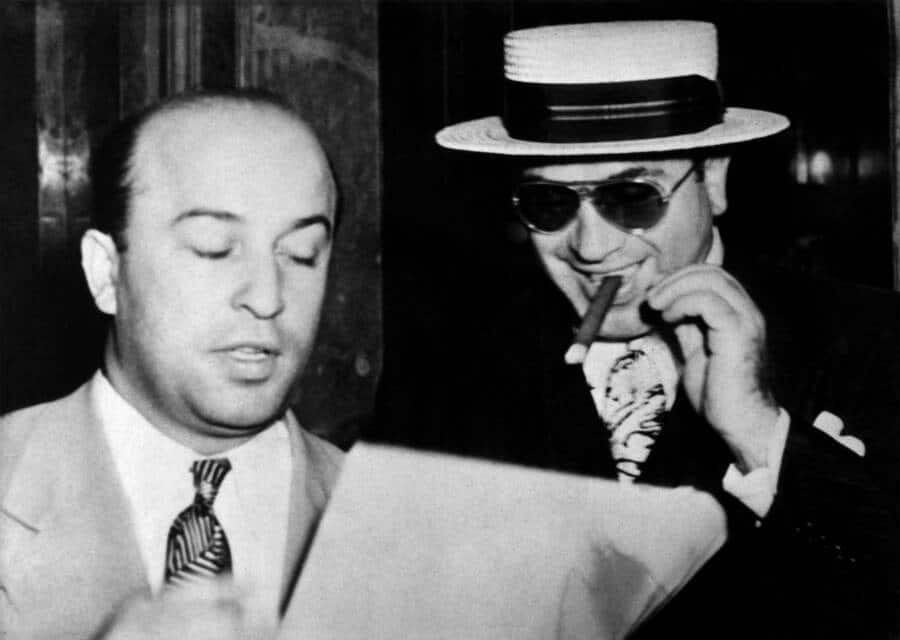

The most notable figure was Eliot Ness, whose team of ‘untouchables’ played a crucial role in the investigation and arrest of notorious gangster Al Capone.

Gangsters who thrived on bootleg alcohol

During Prohibition, the illegal production and sale of alcohol, known as “bootlegging,” thrived across the United States. The rise of bootlegging also sparked a surge in criminal activity.

Prohibition turned crime into a national, organized enterprise. Gangsters became wealthy and influential, often involving business people and politicians in their illegal activities.

Rival gangs fought fiercely for control, leading to over 500 gangland murders between 1927 and 1930. Chicago saw particularly high levels of violence, with claims of 729 gangland killings between 1919 and 1933, though some historians argue these numbers were exaggerated.

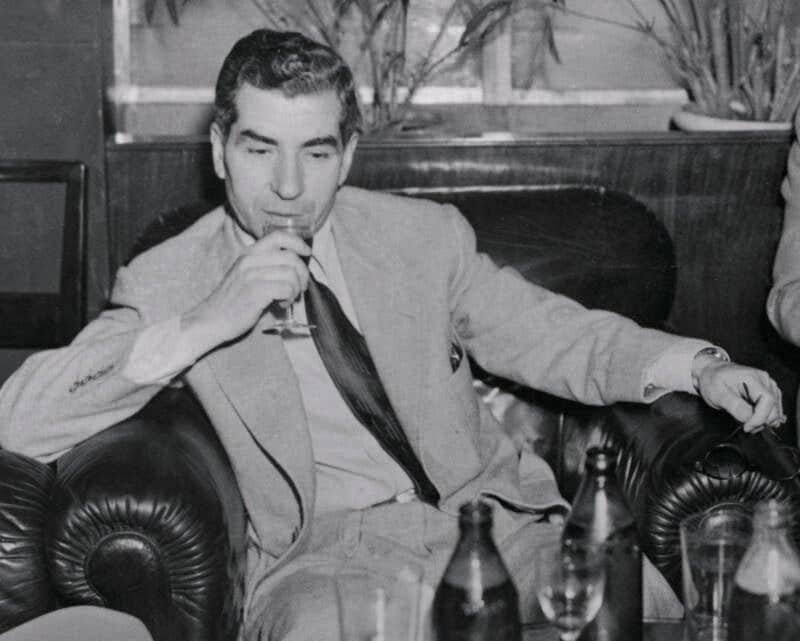

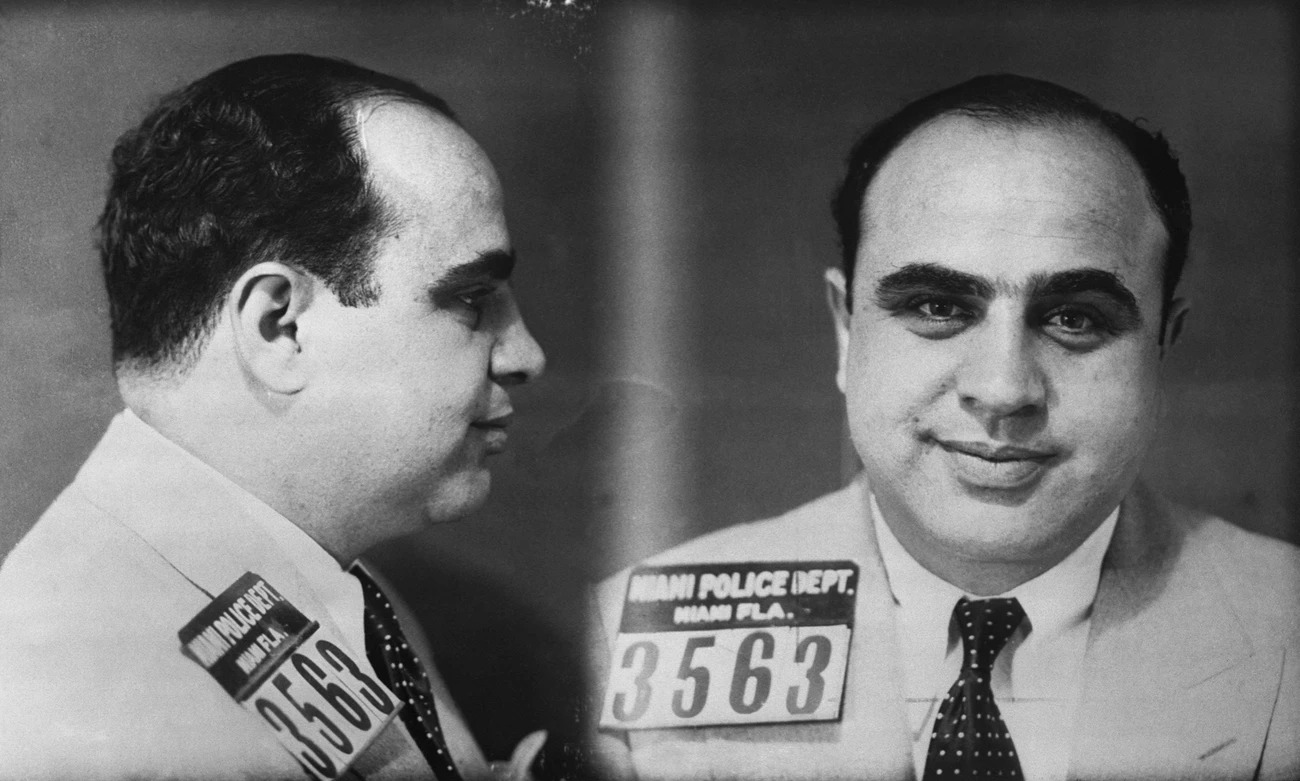

The most notorious criminal of the Prohibition era was Al Capone, who raked in $60 million annually from his illegal activities. His empire spanned speakeasies, bootlegging, gambling, and prostitution.

His reign was marked by brutal rivalries, including clashes with gangsters like Dion O’Bannion and George ‘Bugs’ Moran.

The surge in gang violence reached a peak with the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre of 1929, where Capone’s men, disguised as police, murdered seven rival gang members.

Despite his fearsome reputation, Al Capone faced relentless violence and ultimately retreated in 1927. His criminal empire began to crumble, and in 1931, Capone was convicted of income tax evasion. He received an 11-year prison sentence.

After serving his time, Capone was released in 1939 and retired to his home in Florida. His health declined over the years, and he passed away in 1947.

Effects and reasons for its downfall

The high cost of illegal alcohol hit the working class and poor the hardest, while wealthier people could still get drinks.

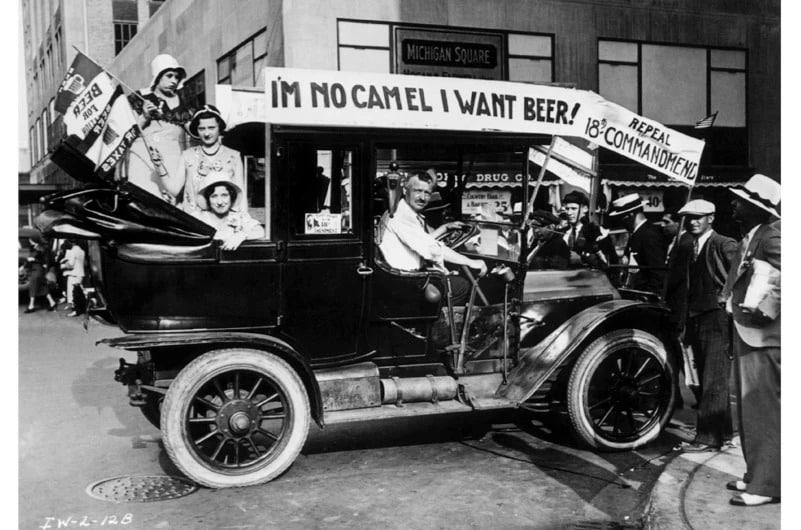

As the Roaring Twenties ended, the costs of enforcing the ban and the growing influence of strict temperance groups led to a loss of support for Prohibition.

The ban led to many problems: restaurants that relied on alcohol sales closed, people died from drinking dangerous homemade liquor, and states lost money from liquor taxes.

The Great Depression made the idea of legalizing alcohol to create jobs and generate revenue very attractive.

By 1932, Franklin D. Roosevelt campaigned to end Prohibition and won against President Herbert Hoover. Despite some initial health benefits from reduced drinking, the rise in crime and the economic impact made it clear that Prohibition was a failure.

President Roosevelt famously captured the mood of the nation with his 1932 remark, “What America needs now is a drink.” The push for repeal gained momentum as the country struggled with the economic hardships of the Depression.

The end of Prohibition

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s victory marked the end of Prohibition. In February 1933, Congress proposed that the 21st Amendment repealed the 18th Amendment, which banned alcohol.

This was a major shift in American policy, driven by a widespread desire to address the issues caused by Prohibition.

By December 1933, Utah cast the 36th and final vote needed to ratify the 21st Amendment, officially ending Prohibition. This momentous change restored legal alcohol sales across the country.

Despite the return of legal alcohol, some states maintained their prohibition laws until 1966.