How Kids Were ‘Mailed’ Through Postal Service

In the early days of the U.S. postal service, people tested the limits of what could be delivered by mail. While today we rely on the post office for packages and letters, there was a time when parents mailed their children.

Yes, you read that right—children were sent through the mail. This surprising method was used to send children to grandparents and relatives.

Discover the fascinating and true history of children being mailed—a quirky part of postal history!

The Birth of Parcel Post Service in America

On January 1, 1913, the United States Postal Service launched Parcel Post to handle large packages. Before this innovation, private companies dominated long-distance deliveries.

However, with the introduction of Parcel Post, rural communities gained access to postal services for all types of goods. But it didn’t take long for Americans to push the boundaries of what could be sent.

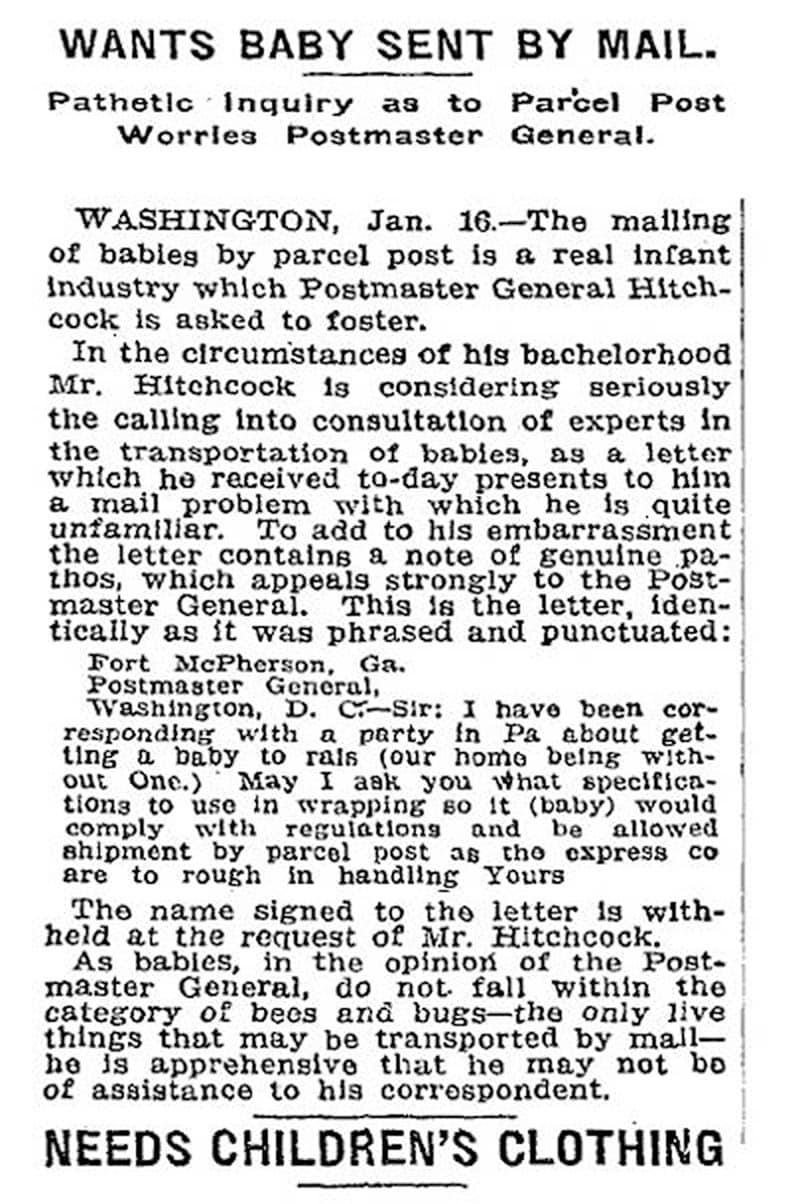

Soon after its launch, the first headlines about people mailing children began to emerge. In these early years, the postal regulations weren’t as strict as they are today. As a result, families across the country experimented with sending their little ones through the mail.

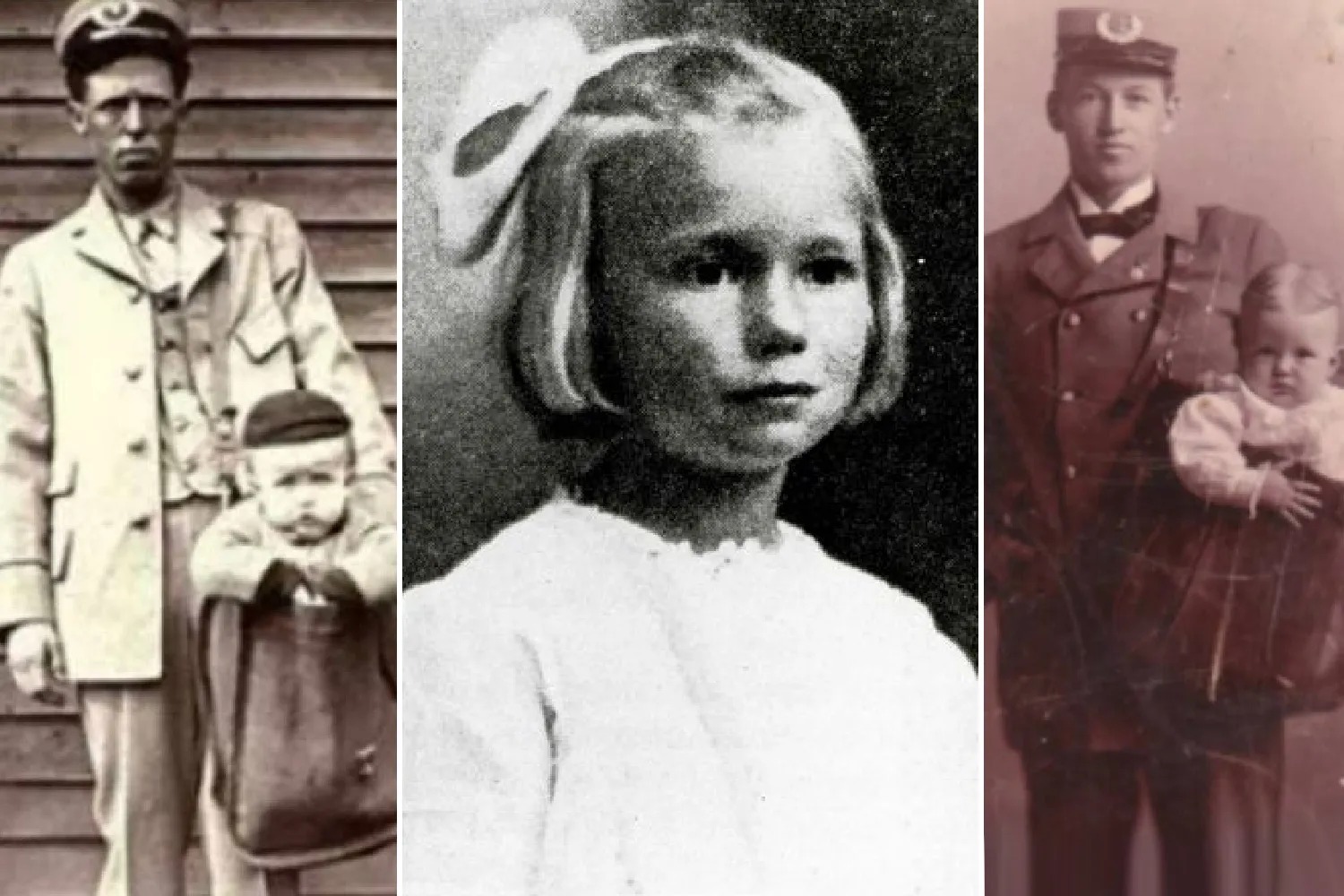

The story of mailed children began in January 1913 when Jesse and Mathilda Beagle of Glen Este, Ohio, “mailed” their 8-month-old son, James, to his grandmother just a few miles away.

James weighed just under the 11-pound limit, so his parents paid 15 cents in postage and insured him for $50. The Beagle baby’s delivery was safe and uneventful, but the quirky tale quickly spread through the press, sparking a trend that would last several years.

While this might seem strange today, at the time, families in rural America trusted their local mail carriers deeply.

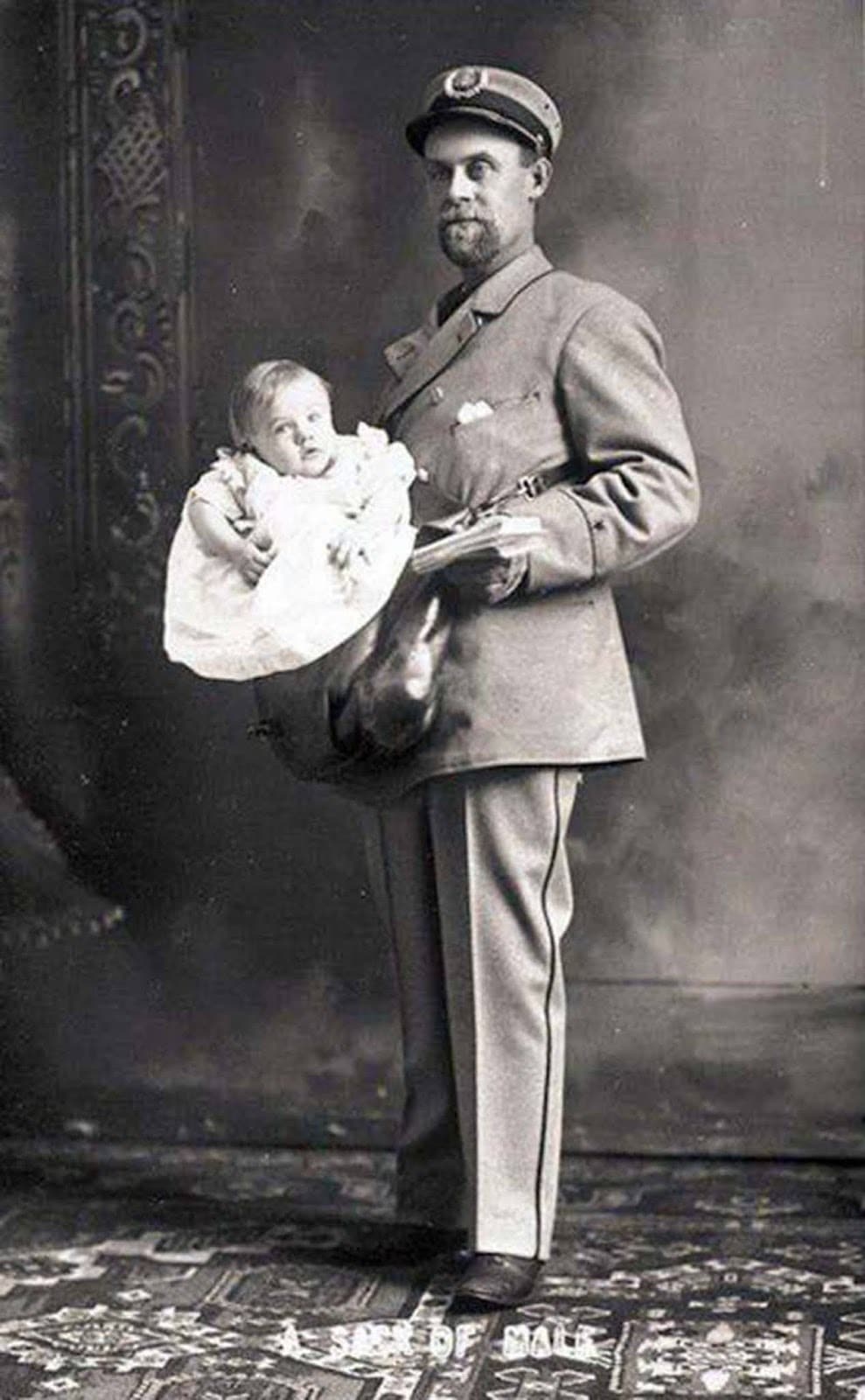

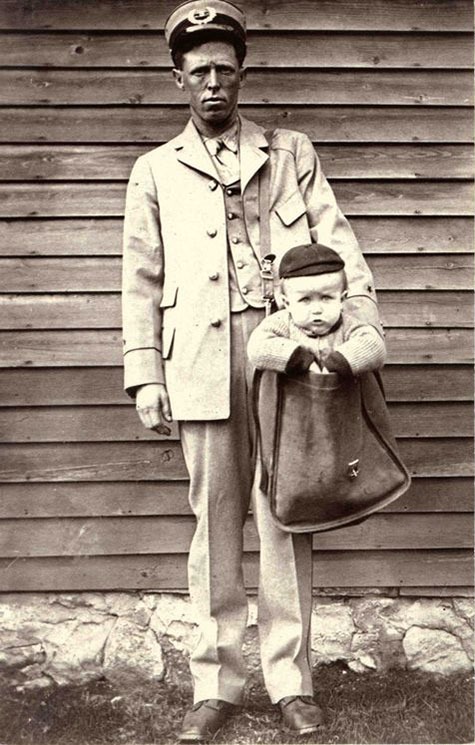

Postal workers often served as trusted members of the community, delivering much more than letters—they helped deliver goods, checked on the sick, and, in some cases, babies.

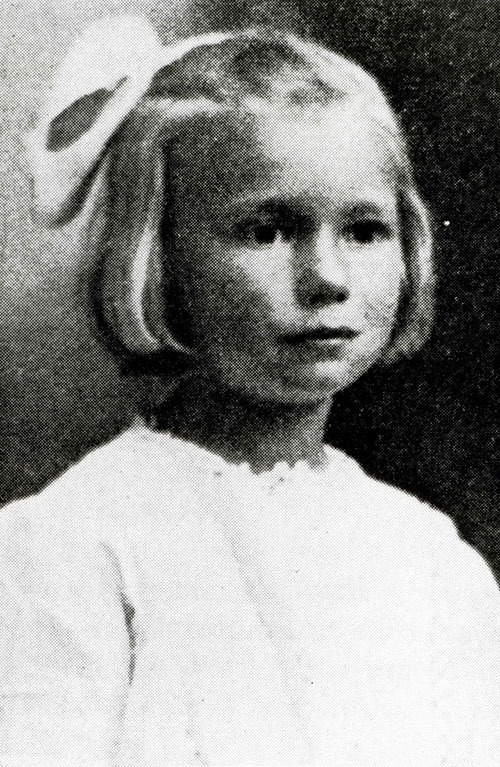

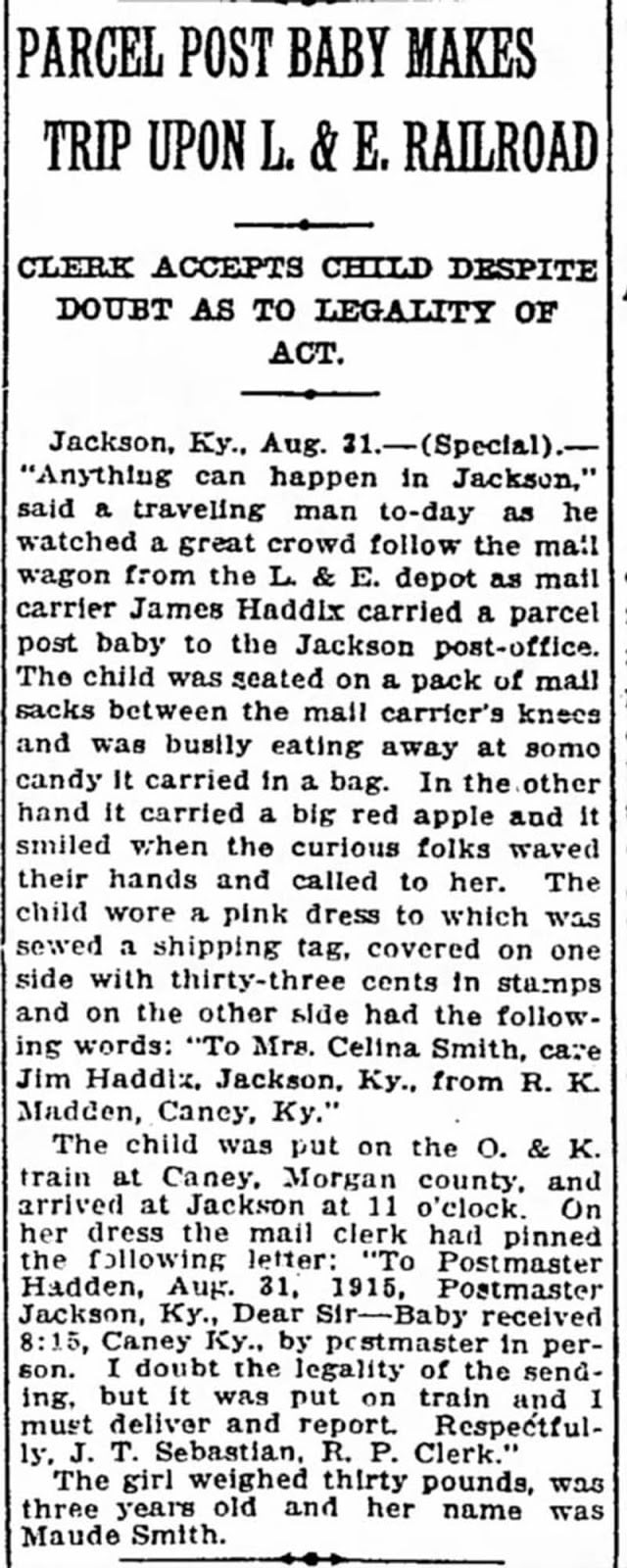

May Pierstorff: The Famous Idaho Case of Mailing a Child

Perhaps the most well-known case of a mailed child was that of 5-year-old Charlotte May Pierstorff. On February 19, 1914, her parents mailed her 73 miles from Grangeville, Idaho, to her grandparents’ home in Lewiston.

Weighing just under the 50-pound limit for parcels, May’s “delivery” cost only 53 cents—cheaper than a train ticket.

Under the care of her relative, a Railway Mail Service clerk, May safely traveled by train with her postage attached to her coat.

May’s journey became so famous that it inspired the children’s book “Mailing May,” which tells the whimsical tale of her postal trip. It also prompted the Postmaster General to take action.

Regulations Are Tightened

By the time May Pierstorff’s case made headlines, postal officials were already rethinking the limits of Parcel Post.

In 1914, Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson officially prohibited mailing children, stating that humans were not considered proper mail. Despite the new regulation, a few more cases of mailed children occurred.

For instance, in 1915, a 6-year-old named Edna Neff was sent 720 miles from Pensacola, Florida, to her father’s home in Christiansburg, Virginia. Her trip marked the longest postal journey for a child, but it was also one of the last.

Why Did People Mail Their Children?

While the idea of mailing a child seems bizarre today, the practice made sense in the context of early 20th-century America. During this time, train travel could be expensive, especially for rural families.

Mailing a child was a cheaper alternative, and families often knew the local mail carrier personally, which added a layer of trust to the arrangement.

Additionally, these children were never simply dropped off at the post office and placed in mail sacks. They were often accompanied by trusted postal workers, making their trips more akin to a modern-day courier service than a traditional postal delivery.

The End of the Practice

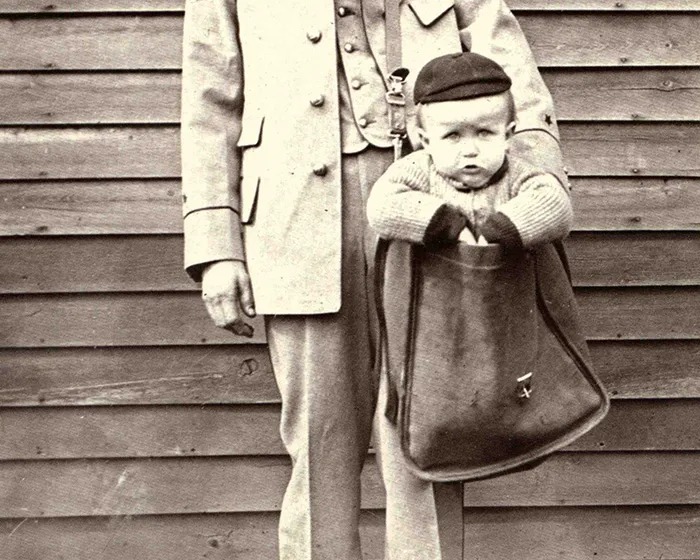

The last recorded case of a child being mailed occurred in 1915 when 3-year-old Maud Smith was sent 40 miles across Kentucky to visit her sick mother.

After this case, postal authorities strictly enforced the ban on mailing children. By 1920, even attempts to mail children were explicitly rejected, and the brief, odd chapter in postal history came to an end.

Postal historian Nancy Pope noted, “Mail carriers were trusted servants… they delivered more than just mail—they delivered life.”