How A Filipina Spy Used Her Leprosy To Outsmart The Japanese In WWII

Leprosy, historically one of the most feared and misunderstood diseases, often led to forced isolation and exile. Patients treated as inmates were barred from leaving hospitals or receiving visitors.

Many chose to forget their past lives, but Josefina Guerrero forged a different path. As her disease progressed, she decided to live with honor.

With the Philippines under cruel occupation, she joined the Philippine Resistance. Her leprosy, which others saw as a curse, became her unique cover in the fight for freedom.

Guerrero enjoyed a fulfilling life before leprosy.

Josefina Veluya, known later as Joey Guerrero, was born in 1917 in Quezon Province, Philippines. Her early life was marked by hardship; she was orphaned young and battled childhood tuberculosis.

Despite these challenges, she thrived in music, poetry, and sports. In 1934, she married Renato Maria Guerrero, a medical student, and they had a daughter named Cynthia. They settled into a promising life in Manila.

By 1939, as war erupted in Europe, Joey began experiencing aches, fever, and skin blotches. In 1941, she was diagnosed with leprosy, a disease greatly feared for its supposed high contagion.

To avoid societal stigma and the threat of being sent to a leprosarium, her family tried to manage her condition discreetly.

Her once happy and stable family life began to fall apart as war in Asia approached. Treatments for her leprosy were limited, offering only slight relief.

When the Japanese occupied the Philippines in 1942, Joey lost access to medication. Her husband moved out, and her young daughter was taken away from her care.

Ben Montgomery, author of “The Leper Spy: The Story of an Unlikely Hero of World War II,” highlights the profound impact of her diagnosis, stating, “It’s hard to imagine more jarring, traumatic circumstances…you’re done, you’re an outcast.”

This marked the beginning of her extraordinary journey from a loving mother to a courageous spy in World War II.

She became a spy and joined the Philippine Resistance.

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, led to assaults on air bases in the Philippines. By January 1942, Japanese forces invaded, clashing with Filipino and American troops led by General Douglas MacArthur.

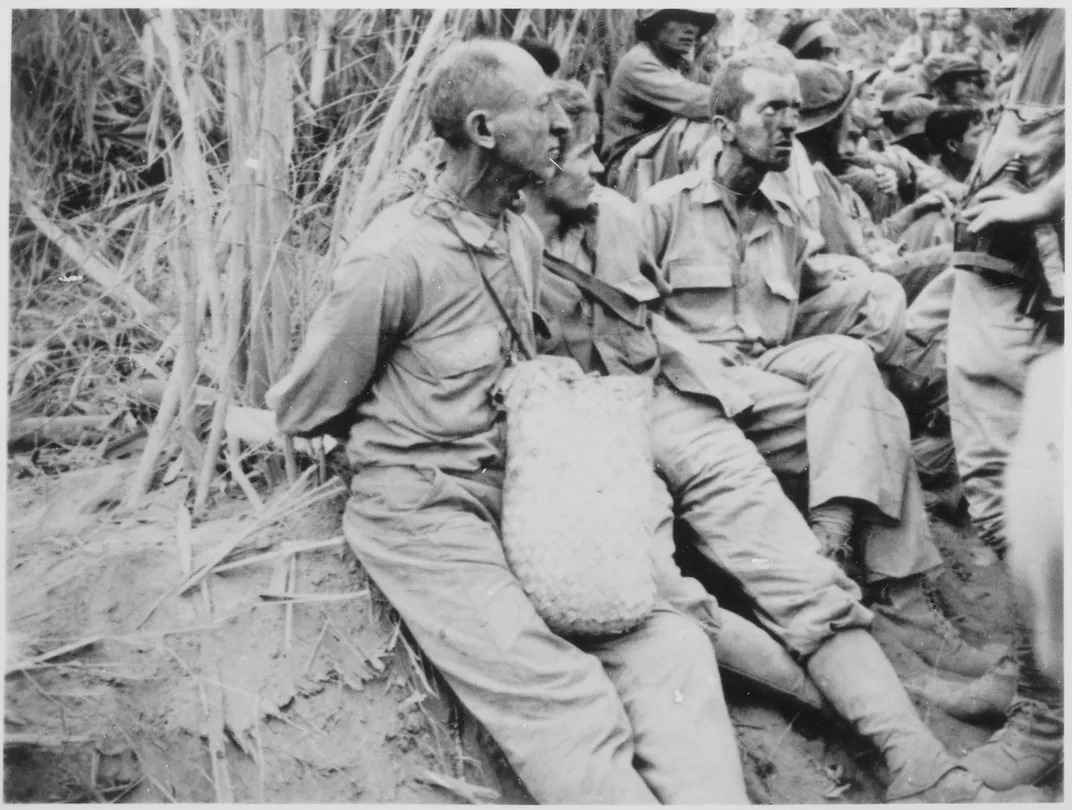

The starving Allied forces surrendered on April 9, 1942, resulting in the brutal Bataan Death March, which claimed around 10,000 lives.

MacArthur’s promise to return sparked a disorganized resistance among Filipino guerrillas, who provided crucial intelligence to the Allies. MacArthur acknowledged their vital role in gathering precise information on enemy movements, paving the way for the American return.

Guerrero was one of these brave resisters. Despite her personal and national tragedy, she chose to help the Allies, saying, “It didn’t really matter whether I lived or died.”

Forced to wear a bell and announce herself as “unclean,” Guerrero turned this stigma into an advantage. Initially wary, Japanese soldiers eventually let her pass with minimal scrutiny, fearing her leprosy.

She used her illness to move undetected through Japanese-occupied areas.

Throughout her espionage, Josefina Guerrero observed Japanese troops and mapped their positions, using her leprosy to pass through checkpoints unnoticed. The Japanese let her move around with less scrutiny due to their fear of her disease.

She cleverly hid messages in her hair and between pairs of socks to deliver war updates to Filipinos under Japanese control. She also pretended to be a laundress to avoid suspicion.

Her work was extremely dangerous, especially in occupied Manila, where capture meant brutal torture and death. Despite close calls, such as when a guard found a hidden note in her hair, she remained undeterred.

As American troops neared, her missions grew riskier. Her map of Japanese fortifications helped American bombers target Japanese defenses in Manila Harbor in 1944.

In January 1945, Guerrero faced her most dangerous task: delivering a map of Manila’s minefields to American headquarters 35 miles away. She taped the map to her back and set off through Japanese checkpoints and guards.

She walked 25 miles to Malolos, took a boat to avoid combat zones and river pirates, and then continued on foot. Upon arrival, she found the Americans had moved to Malolos, so she doubled back to deliver the map to an officer of the 37th Infantry Division.

Despite her exhaustion, her efforts enabled the Americans to advance through the minefields safely. During the Battle of Manila, Guerrero continued to aid the troops by caring for the wounded and rescuing children.

After the war, she struggled to improve the terrible conditions at a leprosarium

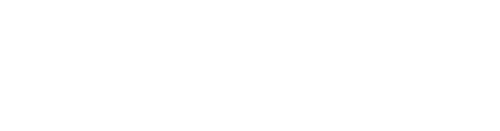

After the war, Joey Guerrero’s disease made her an outcast once again. She was sent to a leprosarium 15 miles northeast of Manila, where conditions were terrible.

With only four nurses for 650 patients and no running water or electricity, many patients slept on the ground and died from malnutrition. Guerrero worked to clean the camp, taught other patients, and built coffins for the deceased.

She wrote a letter detailing these conditions, which reached a Catholic Chaplain in the U.S. and eventually led to a major exposé in the Manila Times.

The government responded by improving the leprosarium, building new dormitories, adding medical staff, and providing better food rations and facilities. Guerrero’s efforts significantly improved life for the patients there.

She lived the rest of her life as a U.S. citizen

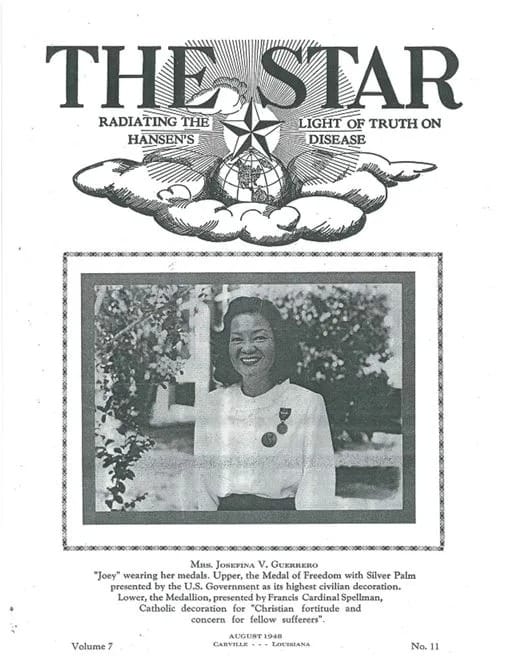

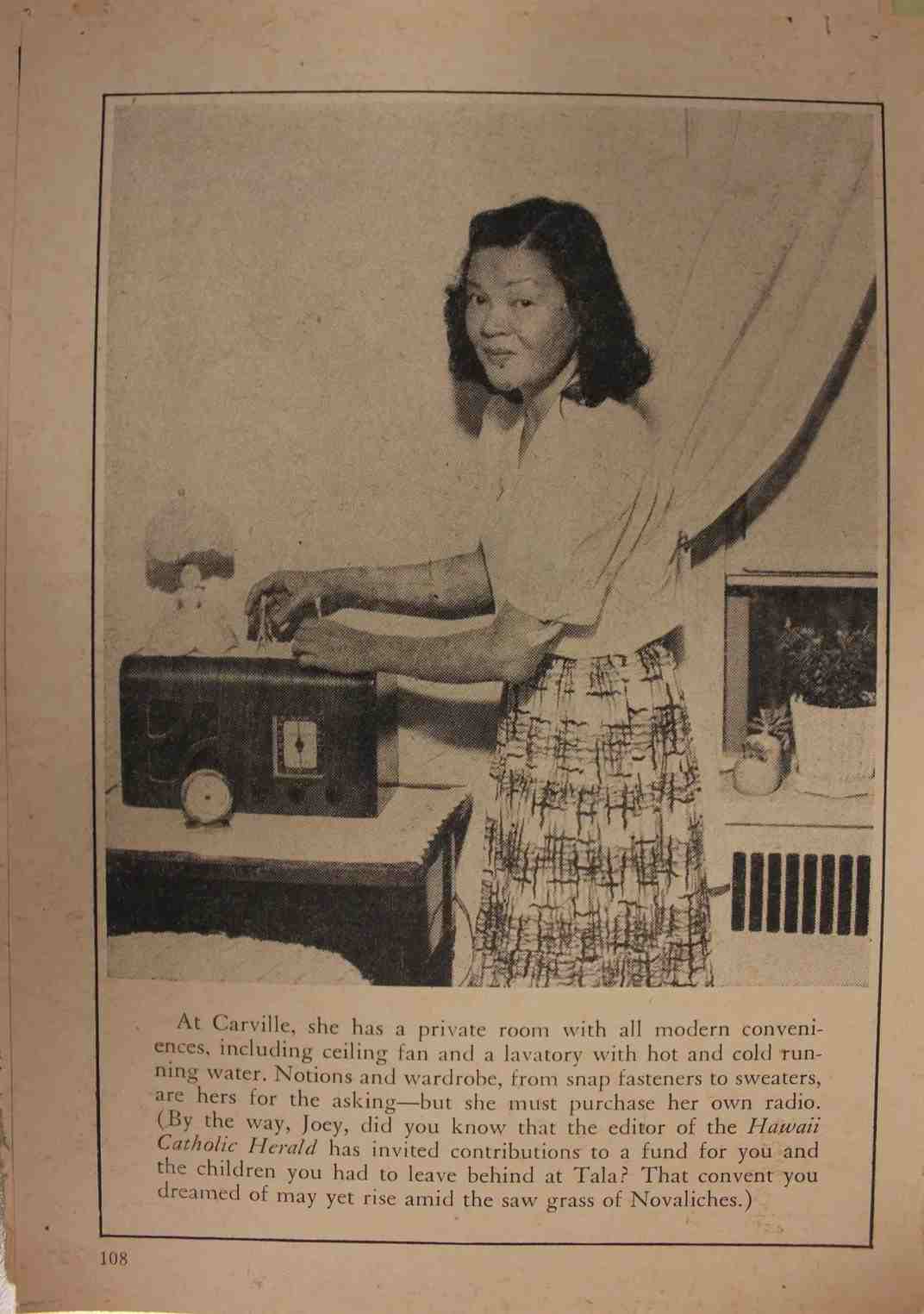

After learning about medical advances in the U.S., Joey Guerrero secured the first American visa for a foreign national with leprosy and arrived in Carville, Louisiana, in 1948.

Following nine years of treatment, she fought against discrimination and was eventually discharged in 1957.

Despite her disease being dormant, Guerrero struggled to find work and faced potential deportation. However, WWII veterans and the press rallied to secure her permanent residency and citizenship in 1967.

She spent the rest of her life in the U.S. until she passed away in 1996.

Guerrero changed her name, earned two degrees, and served in the Peace Corps, and moved to various cities, including San Francisco, Madrid, and Washington D.C. Those who knew her were unaware of her past, and those from her past thought she was dead.