From Humble To Extraordinary: The Inspiring Story Of Edmonia Lewis

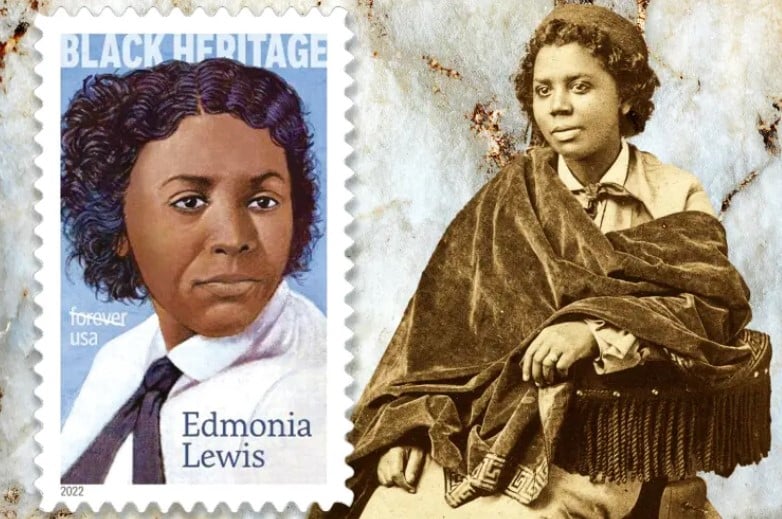

Edmonia Lewis was born in New York around 1844, but there’s not much known about her early years or her parents. Her mother, of mixed African and Native American descent, was skilled in weaving and craftsmanship, while her father, of African American heritage, was known as a writer.

According to the American National Biography, Lewis “was often inconsistent in interviews even with basic facts about her origins, preferring to present herself as the exotic product of a childhood spent roaming the forests with her mother’s people.”

While her background raised many questions, there was no doubt about her exceptional talent as a sculptor. Edmonia Lewis is regarded as one of the best sculptors. People traveled from all over the world to see her art and watch her at work.

Edmonia Lewis’s Harsh Life Before Becoming A Sculptor

Both her parents passed away when Edmonia was just 9 years old. Then, she was raised by her aunts along with her older half-brother. Together, they faced the challenges of life’s hardships. To make ends meet, Lewis and her aunts sold various Native American goods, including Ojibwe baskets, moccasins, and embroidered blouses, to tourists visiting Niagara Falls, Toronto, and Buffalo. During this period, Lewis went by her Native American name, Wildfire, while her brother was known as Sunshine.

Despite the tragedies within her family, Edmonia found a glimmer of financial hope through her half-brother. He ventured to California during the Gold Rush, where he struck gold and achieved wealth.

In 1856, Lewis enrolled in a pre-college program at New York Central College, a Baptist abolitionist school. It was at McGrawville where she encountered numerous prominent activists who would later become her mentors, supporters, and potential subjects for her art as her career blossomed. Looking back in an interview, Lewis mentioned leaving the school after three years due to being labeled as “wild.”

“ Until I was twelve years old I led this wandering life, fishing and swimming…and making moccasins. I was then sent to school for three years in McGrawville, but was declared to be wild—they could do nothing with me.”

However, despite the claims of her unruliness, her academic records at Central College from 1856 to fall 1858 tell a different story. Her grades, conduct, and attendance were all outstanding. Lewis’s coursework encompassed various subjects including Latin, French, grammar, arithmetic, drawing, composition, and declamation.

Edmonia Lewis “Dark” College Years: Be Falsely Accused, Beated, Subject To Daily Racism

In 1859, when Edmonia Lewis was around 15, her brother Samuel and abolitionists sent her to Oberlin, Ohio. There, she attended the secondary Oberlin Academy Preparatory School for the full three-year course. Later, she entered Oberlin Collegiate Institute, which became Oberlin College in 1866. Oberlin was one of the first U.S. higher-learning institutions to admit women and people of different ethnicities.

At Oberlin, she changed her name to Mary Edmonia Lewis and began studying art. She was among only 30 students of color. Mary later revealed that she faced daily racism and discrimination. Along with other female students, she rarely got the chance to participate in class or speak at public meetings.

Mary said that she was subject to daily racism and discrimination. She, and other female students, were rarely given the opportunity to participate in the classroom or speak at public meetings.

During the winter of 1862, an incident occurred between Lewis and two Oberlin classmates, Maria Miles and Christina Ennes. It happened a few months into the US Civil War. All three women were staying in Keep’s home at the time. They had made plans to go sleigh riding with some young men later that day. Before they set out, Lewis offered her friends a drink of spiced wine.

Shortly after drinking the wine, Miles and Ennes fell seriously ill. Doctors examined them and determined that they had been poisoned, supposedly with cantharides, a substance believed to be an aphrodisiac. At first, it was uncertain whether they would survive. However, in the following days, it became evident that the two women would recover from the ordeal. Initially, authorities did not take any immediate action.

News of the controversial incident spread quickly throughout Ohio. One night, as she walked home alone, she was ambushed by unknown assailants, dragged into an open field, brutally beaten, and left for dead.

After the attack, local authorities arrested Lewis and accused her of poisoning her friends. John Mercer Langston, an Oberlin College alumnus and Ohio’s first African-American lawyer, took up Lewis’s case. Despite numerous witnesses testifying against her and her decision not to take the stand, Langston successfully argued for the dismissal of the charges. The lack of evidence, including the absence of stomach contents analysis from the victims, led to the charges being dropped.

During the rest of her time at Oberlin, Lewis faced isolation and discrimination. Around a year after the trial for poisoning, she was accused of stealing artists’ materials from the college. Despite the accusations, she was cleared due to insufficient evidence. Just a few months later, she faced charges of aiding and abetting a burglary. Frustrated by these experiences, she decided to leave. Another account suggests that she was barred from enrolling for her final term, preventing her from graduating.

The Incredible Journey To Be A Sculptor

After finishing college, Lewis made her way to Boston in early 1864 and started to pursue her career as a sculptor. She repeatedly told a story about stumbling upon a statue of Benjamin Franklin in Boston, initially unsure of what it was but ultimately deciding she could craft her own “stone man.”

The Keeps introduced her to established sculptors and writers in the area, garnering attention for Lewis in abolitionist publications. However, finding a mentor was challenging. Finally, Edward Augustus Brackett, who specialized in marble portrait busts decided to instruct her.

He lent her fragments of sculptures to practice copying in clay. With Brackett’s guidance, she even fashioned her own sculpting tools and sold her first piece, a sculpture of a woman’s hand, for $8. In 1864, Lewis proudly opened her studio to the public for her inaugural solo exhibition.

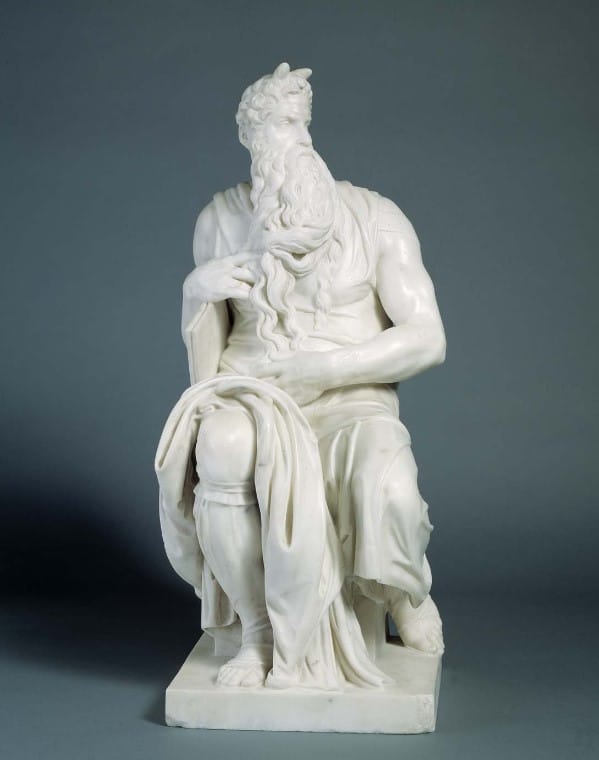

Inspired by the stories of abolitionists and heroes of the Civil War, Edmonia Lewis found her muse in Union Colonel Shaw, the leader of a Massachusetts African-American Civil War regiment. After creating a striking bust of Colonel Shaw, Lewis gained the admiration of his family, who purchased the sculpture. Capitalizing on its success, she produced plaster-cast reproductions, selling a hundred at $15 each. While Lewis recognized that not everyone fully appreciated her art, she saw it as a means to express her support for human rights.

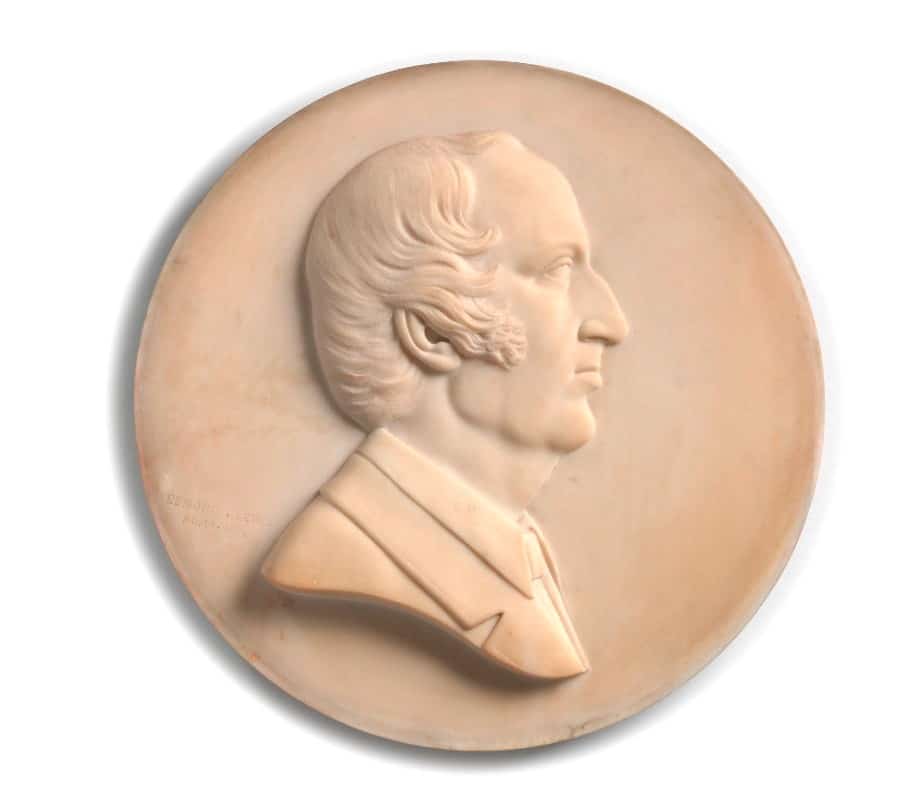

Edmonia spent the money she earned from the busts to move to Rome. In her early career, Edmonia Lewis gained popularity with her medallion portraits of abolitionists like John Brown and Wm. Lloyd Garrison, whom she admired. She also drew inspiration from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem, “The Song of Hiawatha,” creating several busts of its characters from Ojibwe legend.

“I was practically driven to Rome in order to obtain the opportunities for art culture, and to find a social atmosphere where I was not constantly reminded of my color. The land of liberty had no room for a colored sculptor.”

The success and popularity of the works she created in Boston (particularly the reproductions of her bust of Shaw) allowed Lewis to bear the cost of a trip to Rome in 1866. Lewis spent most of her adult career in Rome, where Italy’s less pronounced racism allowed increased opportunity to a black artist.

During her time in Rome, Lewis continued to thrive as an artist and received a prestigious commission from former President Ulysses S. Grant in 1877. She also contributed a bust of Massachusetts abolitionist senator Charles Sumner to the 1895 Atlanta Exposition. However, details about her later years remain unknown.

Some of Her Outstanding Artworks