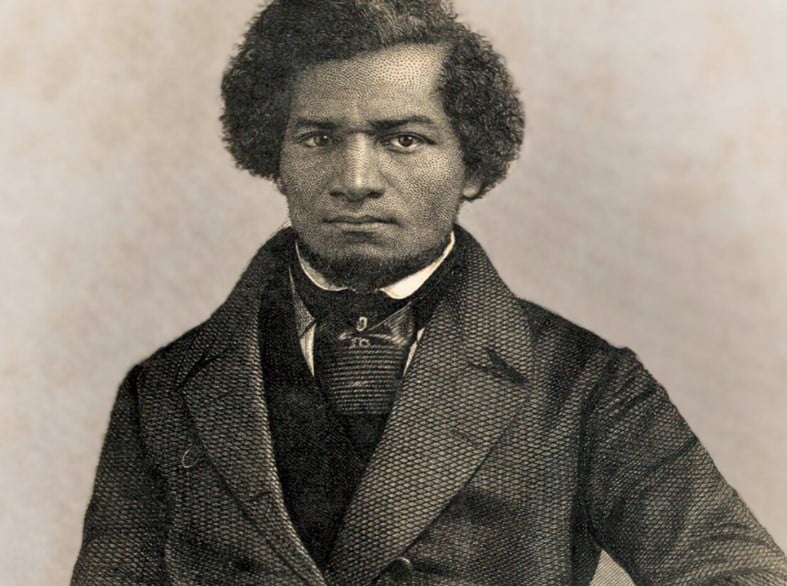

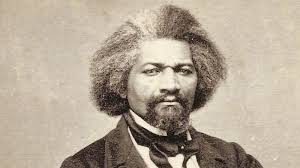

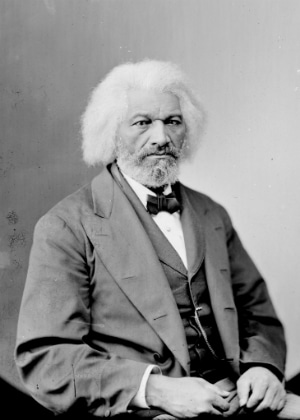

Frederick Douglass’ Extraordinary Life: From A Slave To A Social Reformer

Frederick Douglass was a prominent African American abolitionist, writer, and social reformer. Born into slavery on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay in Talbot County, Maryland, he escaped to freedom and became one of the leading voices against slavery in the United States during the 19th century.

Douglass’s Tough Childhood

In his first autobiography, Douglass stated, “I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it.” Though he did not know the exact date of his birth, he chose to mark February 14 as his birthday, a tribute to his mother’s endearment of him as her “Little Valentine.”

Douglass’s mother, herself enslaved, came from African heritage, while his father, potentially her master, likely had European ancestry. According to David W. Blight’s 2018 biography of Douglass, “For the rest of his life he searched in vain for the name of his true father.”

Douglass’s mother, herself enslaved, came from African heritage, while his father, potentially her master, likely had European ancestry. According to David W. Blight’s 2018 biography of Douglass, “For the rest of his life he searched in vain for the name of his true father.”

He later wrote of his earliest times with his mother:

“The opinion was also whispered that my master was my father; but of the correctness of this opinion, I know nothing. …My mother and I were separated when I was but an infant…. It is a common custom, in the part of Maryland from which I ran away, to part children from their mothers at a very early age…. I do not recollect of ever seeing my mother by the light of day. She was with me in the night. She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone. “

During his childhood, Frederick lived with his maternal grandmother Betsy Bailey, who was also enslaved, and his maternal grandfather Isaac, who was free. Sadly, Frederick’s mother had limited visits before passing away when he was just 7 years old.

Years later, around 1883, Frederick returned to Talbot County to buy land that held significant meaning for him. During this visit, he was invited to speak at a “colored school.”

“I once knew a little colored boy whose mother and father died when he was six years old. He was a slave and had no one to care for him. He slept on a dirt floor in a hovel, and in cold weather would crawl into a meal bag head foremost and leave his feet in the ashes to keep them warm. Often he would roast an ear of corn and eat it to satisfy his hunger, and many times has he crawled under the barn or stable and secured eggs, which he would roast in the fire and eat.

That boy did not wear pants like you do, but a tow linen shirt. Schools were unknown to him, and he learned to spell from an old Webster’s spelling-book and to read and write from posters on cellar and barn doors, while boys and men would help him. He would then preach and speak, and soon became well known. He became Presidential Elector, United States Marshal, United States Recorder, United States diplomat, and accumulated some wealth. He wore a broadcloth and didn’t have to divide crumbs with the dogs under the table. That boy was Frederick Douglass.”

The Indomitable Spirit Despite The Adversity Of Fate

At 6 years old, Douglass was taken from his grandparents and relocated to the Wye House plantation. Soon after, he was transferred to serve Thomas’ brother, Hugh Auld, and his wife, Sophia Auld, in Baltimore. Upon his arrival, Sophia ensured Douglass had proper food, clothing, and a comfortable bed—a stark contrast to the harsh conditions on plantations. Douglass felt fortunate to be in the city, where enslaved individuals enjoyed a semblance of freedom.

When he turned 12, Sophia Auld began teaching him the alphabet but Hugh Auld opposed the idea, feeling that literacy would instill in slaves a desire for freedom. Under her husband’s influence, Sophia stopped teaching him.

Douglass continued, secretly, to teach himself to read and write. He later said, “knowledge is the pathway from slavery to freedom.” As Douglass immersed himself in newspapers, pamphlets, and books, his expanding intellect fueled his condemnation of slavery. He later learned that his mother had also been literate, about which he would later declare:

“ I am quite willing, and even happy, to attribute any love of letters I possess, and for which I have got—despite of prejudices—only too much credit, not to my admitted Anglo-Saxon paternity, but to the native genius of my sable, unprotected, and uncultivated mother—a woman, who belonged to a race whose mental endowments it is, at present, fashionable to hold in disparagement and contempt.”

The Journey To Freedom

In 1833, Douglass was sent to work for Edward Covey, a poor farmer said as a “slave-breaker”. Covey’s relentless beatings left Douglass physically and emotionally shattered. He whipped Douglass so frequently that his wounds had little time to heal. The 16-year-old Douglass eventually fought back and won, putting an end to Covey’s attempts to break him.

In 1837, Douglass met Anna Murray, a free black woman in Baltimore, whom he fell deeply in love with. Murray’s freedom fueled Douglass’s desire for his own emancipation. Murray encouraged him and supported his efforts by aid and money.

Douglass seized the opportunity to escape slavery by boarding a northbound train from Baltimore. Recent research suggests he boarded the train at Canton Depot in the Canton neighborhood of Baltimore. With Murray’s help of providing him with a sailor’s uniform and money, Douglass carried identification and protection papers obtained from a free black seaman.

Douglass crossed the wide Susquehanna River by the railroad’s steam-ferry and then continued by train across the state line to Wilmington. He went by steamboat along the Delaware River farther northeast to the “Quaker City” of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, an anti-slavery stronghold. Finally, he found refuge in New York City at the home of abolitionist David Ruggles. Remarkably, Douglass completed his journey to freedom in less than 24 hours. Douglass later wrote of his arrival in New York City:

“I have often been asked, how I felt when first I found myself on free soil. And my readers may share the same curiosity. There is scarcely anything in my experience about which I could not give a more satisfactory answer. A new world had opened upon me. If life is more than breath, and the “quick round of blood,” I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life. It was a time of joyous excitement which words can but tamely describe. In a letter written to a friend soon after reaching New York, I said: “I felt as one might feel upon escape from a den of hungry lions.” Anguish and grief, like darkness and rain, may be depicted; but gladness and joy, like the rainbow, defy the skill of pen or pencil.”

Upon his arrival, Douglass quickly arranged for Murray to join him in New York. they were married just eleven days later, on September 15, 1838, by a black Presbyterian minister.

Douglass Became An Abolitionist And Preacher

After the couple settled in New Bedford, Douglass worked as a minister in a Black Methodist Episcopal church in 1939. This role allowed him to hone his skills as a public speaker. Within the church, Douglass took on various responsibilities, from welcoming congregants to overseeing Sunday School activities and maintaining the church building.

Douglass immersed himself in the abolitionist movement. He attended meetings and joined organizations dedicated to ending slavery. One significant influence on Douglass was William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper, The Liberator, which he avidly subscribed to.

Douglass first heard Garrison speak in 1841 during a lecture at Liberty Hall in New Bedford. It was at this meeting that Douglass was unexpectedly invited to share his story, which led to him being encouraged to become an anti-slavery lecturer. At age 23, overcoming his nervousness, Douglass delivered a powerful speech about his experiences as a slave at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society’s annual convention in Nantucket.

In 1843, Douglass embarked on the American Anti-Slavery Society’s “Hundred Conventions” project, a six-month tour across the eastern and midwestern United States. Throughout the tour, he faced frequent confrontations from slavery supporters. In Pendleton, Indiana, he was chased and beaten by an angry mob, resulting in a broken hand that would trouble him for the rest of his life. Despite the challenges, Douglass’s resilience and eloquence left a lasting impact on audiences across the country.

The Strong Struggle For Women’s Rights And Education

In 1848, Douglass made history as the sole black attendee at the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women’s rights convention, in upstate New York. Douglass stood and spoke eloquently in favor of women’s suffrage, asserting that denying women the right to vote was unjust. He stated:

“In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of women and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world.”

After Douglass’s powerful words, the attendees passed the resolution.

In 1849, Douglass traveled in Ireland as the Great Famine was beginning. The feeling of freedom from American racial discrimination amazed Douglass:

“I gaze around in vain for one who will question my equal humanity, claim me as his slave, or offer me an insult. I employ a cab—I am seated beside white people—I reach the hotel—I enter the same door—I am shown into the same parlor—I dine at the same table—and no one is offended…. I find myself regarded and treated at every turn with the kindness and deference paid to white people. When I go to church, I am met by no upturned nose and scornful lip to tell me, ‘We don’t allow niggers in here!’”

On July 5, 1852, Douglass delivered a powerful address at Corinthian Hall, organized by the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society. This speech, later titled “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” is often considered as one of the greatest anti slavery speeches ever given.

Douglass, like many abolitionists, believed strongly in the importance of education for African Americans to uplift their lives. He was an early advocate for school desegregation. In the 1850s, Douglass saw the stark disparities between educational facilities and opportunities for African American and European American children in New York. Douglass called for court action to open all schools to all children. He said that educational inclusion was more urgent than political issues like suffrage for African Americans.

Douglass’ Death

In 1895, Douglass attended a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. He received a standing ovation during the event. Shortly after returning home from the meeting, he suffered a massive heart attack and died at 77. His funeral was held at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church. Thousands of people passed by his coffin to show their respect.

Facts

- One of the reasons we celebrate Black History Month in February is because of Frederick Douglass.

- Douglass was the most photographed American of the 19th century, sitting for more portraits than even Abraham Lincoln.

- Douglass was the first African American to receive a vote for president at a major political party convention.

- Many of Douglass’ possessions were lost in a devastating fire in 1877.