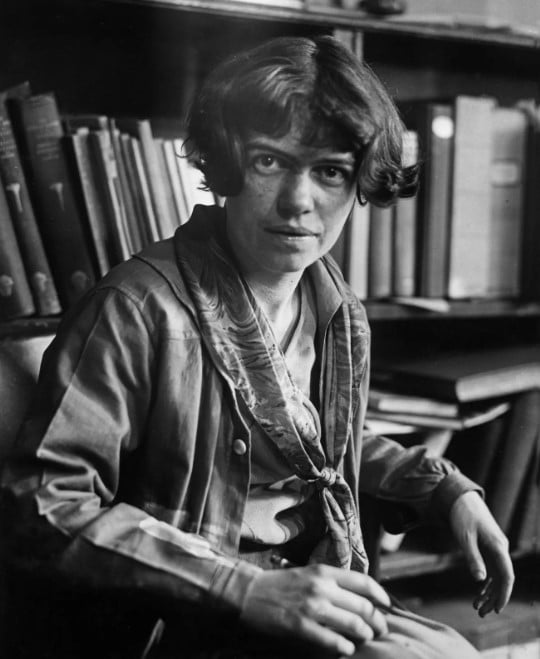

Fascinating Untold Stories About Margaret Mead

“Always remember that you are absolutely unique. Just like everyone else.” This timeless quote is just one of the many pearls of wisdom left by Margaret Mead, a renowned anthropologist whose work continues to inspire and enlighten.

Throughout her life, Mead delved into the complexities of human culture, challenging norms and sparking conversations about identity, diversity, and social change. From her groundbreaking research to her passionate advocacy, Margaret Mead’s legacy remains a beacon of insight and inspiration for generations to come. Join us as we uncover some of the fascinating untold stories behind this remarkable figure.

Margaret’s insight on the First Sign of Civilization

Dr. Ira Byock, in his book on palliative medicine “The Best Care Possible,” wrote about Margaret mead. He said:

“Years ago, anthropologist Margaret Mead was asked by a student what she considered the first sign of civilization in a culture. The student expected Mead to talk about fish hooks or clay pots or grinding stones. But no, Mead said that the first sign of civilization in ancient culture was a femur (thighbone) that had been broken then healed.”

According to the book, she explained, “that in the animal kingdom, if you break your leg, you die. You cannot run from danger, get to the river for a drink or hunt food. You are meat for prowling beasts. No animal survives a broken leg long enough for the bone to heal.”

She then added, “A broken femur that has healed is proof that someone has taken time to stay with the person who has fell, has bound up the wound, has carried the person to safety and has tended the person through recovery. ‘Helping someone through difficulty is where civilization starts’ said Mead. We are at our best when we serve others. Be civilized.”

Margaret’s answer reflects on how simple acts of kindness and care define our humanity. It highlights the idea that true civilization begins when individuals extend compassion and assistance to those in need.

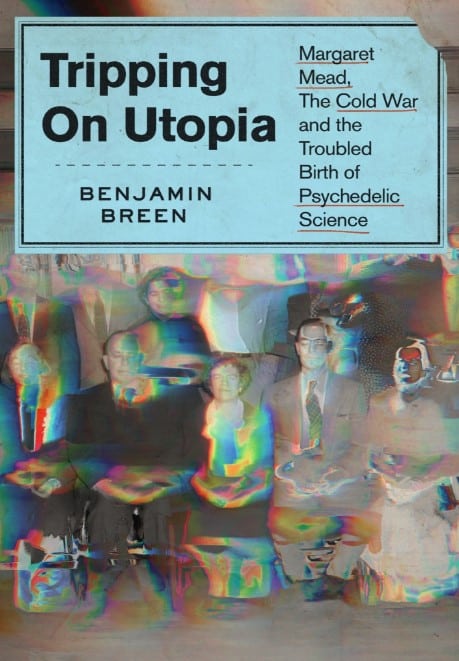

Her research into utopias

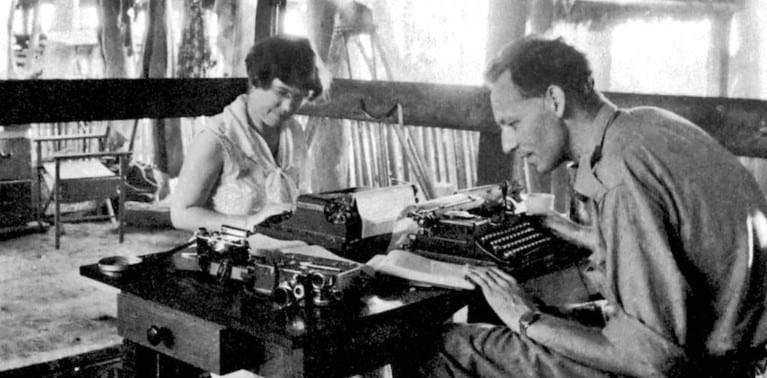

Psychedelic science began much earlier than you may think – back in the 1920s and ’30s. At the forefront of this research were Margaret Mead, the renowned anthropologist, and her third husband, Gregory Bateson, a controversial figure in anthropology during his time.

Amid the aftermath of World War I and the rise of modern technologies like radio and automobiles, Mead and Bateson began envisioning a utopian society influenced by plant-based psychedelics. Their exploration delved into the potential of these substances to shape a better future.

“They saw science as something which was responsible for some of the bad things in the world,” historian Benjamin Breen says, “but also [as] something which could be a tool for fixing the world or healing a sick society.”

Breen, an associate professor of history at the University of California Santa Cruz, delves into Margaret Mead’s fascinating journey into the realm of expanded consciousness and hypnosis. Mead’s interest in psychedelics began in 1930 during her fieldwork on the Omaha Reservation in Nebraska, where she observed the use of peyote among the people there.

“Rather than seeing peyote use among the Omaha as something which predates the modern era and goes back to this ancient tradition, she came to see it as something which was modern,” Breen says. “And it allowed people — and not just the Omaha — but potentially people in the rest of the world, to cope with the rapid technological changes they were going through.”

During World War II, Mead and Bateson collaborated on a team exploring hypnosis and mind-altering drugs to combat Hitler and fascism. This research laid the groundwork for the CIA’s covert experiments with psychedelics in the ’50s and ’60s, which eventually intersected with the counterculture movement of the ’60s, popularizing substances like LSD, mescaline, and magic mushrooms. Later experiments went even further afield, such as attempts to teach dolphins to communicate using LSD.

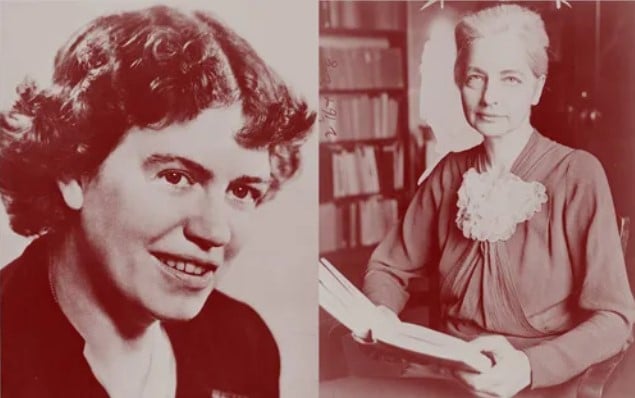

Margaret is bisexual

Although Margaret Mead was married three times, it was her enduring relationship with fellow anthropologist Ruth Benedict that left a lasting impact on her life and work. Together, they challenged conventional notions of what was considered “normal” within different cultures. Mead came to view those labeled as “deviant” as individuals who sought alternative ways of living and rejected traditional societal norms. Her family confirmed her bisexuality and accepted her enduring relationship with Ruth Benedict.