Edith Wharton’s Amazing Life: Defied Societal Norms And Did Extraordinary Things

“There are two ways of spreading light: to be the candle or the mirror that reflects it.” Do you know who said this quote? The remarkable woman we’d like to introduce today is Edith Wharton was an American novelist, known for her insightful portrayals of the upper class in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Wharton broke through these strictures to become one of America’s greatest writers. Author of The Age of Innocence, Ethan Frome, and The House of Mirth, she wrote over 40 books in 40 years, including authoritative works on architecture, gardens, interior design, and travel. She was the first woman awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, an honorary Doctorate of Letters from Yale University, and a full membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Defiance of societal norms by Edith Wharton

Edith Wharton was born into a wealthy family and her family made their money in real estate. The saying “keeping up with the Joneses” is said to be about her father’s side of the family. They were connected to the Rensselaers, a prestigious family that received land grants from the Dutch government in New York and New Jersey. Caroline Schermerhorn Astor, Wharton’s father’s cousin, was part of their family tree. Wharton’s maternal great-grandfather, Ebenezer Stevens, was honored with Fort Stevens in New York, named after his Revolutionary War bravery

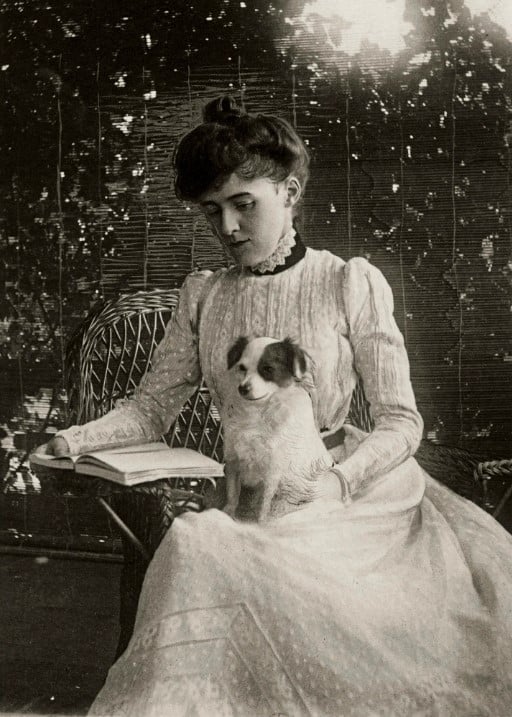

However, Edith Wharton grew up in a society that had strict rules for women, especially when it came to marriage. But Edith wasn’t one to follow the rules – she marched to the beat of her own drum from a young age. Instead of conforming to societal expectations, she pursued her interests with determination, ignoring the norms that dictated how young girls should behave. While other girls focused on fashion and etiquette to attract suitors, Edith charted her own path, uninterested in conforming to expectations just to secure a good marriage and be a socialite at fancy parties.

Her struggles to pursue writing as a career

When Edith was just 4 or 5 years old, she started making up stories for her family. She’d walk around with an open book, pretending to read while creating tales on the spot. She recalled:

“No children of my own age…were as close to me as the great voices that spoke to me from books. Whenever I try to recall my childhood it is in my father’s library that it comes to life…”

She wrote poetry and fiction and tried writing her first novel at the age of 11. By the time she was 15, she had her first published work, a translation of a German poem “Was die Steine Erzählen” (“What the Stones Tell”). She got $50 for it, but her family didn’t want her name on it. They thought writing wasn’t a suitable career for a woman in their society. So, it was published under a friend’s father’s name, E.A. Washburn, who supported women’s education.

In 1880, she got five of her poems published anonymously in the Atlantic Monthly, an important literary magazine. Even though she had these early successes, her family and friends didn’t really encourage her to keep writing.

Her observations of New York’s upper class

Between 1880 and 1890, Wharton took a break from writing to mingle with New York’s upper class. She watched closely as society changed around her, gathering inspiration for her later writing. Wharton officially came out as a debutante to society in 1879. She experienced her first taste of freedom at a dance hosted by Anna Morton, where she could finally show her shoulders and wear her hair up.

In April 1885, Wharton tied the knot with Edward Robbins, a sportsman and a gentleman from the same social circle.

“..he was thirteen years older than myself, but the difference in age was lessened by his natural youthfulness, his good humor and gaiety, and the fact that he shared my love of animals and out-door life, and was soon to catch my travel-fever…”

They shared a passion for travel, embarking on a lavish $10,000 trip together. During this journey, Wharton kept a travel journal, originally thought to be lost. However, it was later discovered and published as “The Cruise of the Vanadis,” now recognized as her earliest known travel writing.

Unfortunately, from the late 1880s to 1902, Teddy Wharton suffered from chronic depression that worsened over time. Despite their 28 years of marriage, Wharton divorced Edward Wharton in 1913, marking the end of their union.

Became “heroic worker” on World War I

When World War I started in 1914, Edith Wharton, a wealthy and famous author who had recently gone through a divorce, found herself in Paris, her beloved city. Instead of leaving for safer places like England or returning to the United States, she stayed and dedicated herself to helping others.

In August 1914, she set up a place where unemployed women could work. She also provided them with food and paid them a little bit each day. What started with 30 women soon grew to 60, and their sewing business started doing really well.

As the war went on and Paris became flooded with refugees from Belgium, Wharton sprang into action again. She helped create places called American Hostels for Refugees, where these people could find shelter, food, and clothes. She even set up a way to help them find jobs. She worked hard and managed to raise over $100,000 to help these refugees. Then, in early 1915, she started the Children of Flanders Rescue Committee. This group took in almost 900 Belgian refugees, especially children, who had to leave their homes because of German bombings.

As a writer, Wharton was intent on witnessing the realities of war and was one of a handful of journalists and writers allowed on the front lines. Traveling by car, Wharton and her long-time friend Walter Berry (then president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Paris) drove through the war zone, viewing one devastated French village after another. She visited the trenches, and was within earshot of artillery fire.

As a writer, Edith Wharton wanted to see the harsh realities of war firsthand. Alongside her friend Walter Berry (then president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Paris), they traveled through war-torn areas, witnessing the devastation of French villages and even visiting the trenches where soldiers fought. Despite the dangers, Wharton organized concerts to support musicians and raised significant funds for the war effort, including the establishment of tuberculosis hospitals.

She wrote, “We woke to a noise of guns closer and more incessant … and when we went out into the streets it seemed as if, overnight, a new army had sprung out of the ground”.

Wharton also organized concerts to provide work for musicians, raising tens of thousands of dollars for the war effort, and opening tuberculosis hospitals.

In 1915, Wharton took on the role of editor for a charity volume called The Book of the Homeless. This unique collection featured contributions from prominent artists and writers, including Henry James, Joseph Conrad, and Jean Cocteau. The book aimed to raise awareness and support for those affected by the war, incorporating essays, art, poetry, and musical scores.

In recognition of her tireless efforts, Edith Wharton was honored by the President of France, Raymond Poincaré, who appointed her as Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in April 1916.

Her later life

At the end of the war, Edith Wharton left Paris and settled in Pavillon Colombe, a cozy villa in St. Brice-sous-Forêt. In 1921, she achieved great success with her novel “The Age of Innocence,” which won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. She also acquired Château Ste.-Claire, a beautiful convent in southern France, in 1920. From then on, she split her time between these two homes, enjoying the company of her friends and beloved dogs, while also staying busy with writing, traveling, and gardening. Despite her move to France, Wharton only visited the United States twice afterward, the last time in 1923 to accept an Honorary Doctorate from Yale University.

While working on a revised edition of her book “The Decoration of Houses,” Wharton suffered a heart attack and collapsed. She passed away on August 11, 1937, at the age of 75, at Pavillon Colombe. She was laid to rest in the Cimetière des Gonards in Versailles, near her close friend Walter Berry. Wharton’s legacy lives on through her timeless literature and enduring influence on the literary world.