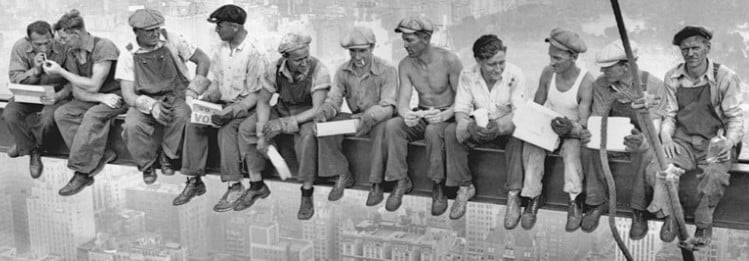

Discover The Backstory Of Iconic Photograph “Lunch Atop A Skyscraper”

For nearly a hundred years, the iconic photograph “Lunch Atop A Skyscraper” has symbolized many aspects from New York City to the Great Depression to America itself. Taken on September 20, 1932, this famous image freezes a moment in time.

In the black-and-white image, 11 intrepid ironworkers sit perched on a steel beam, high 850 feet (260 meters) above the bustling streets of Manhattan, New York City. While its imagery is legendary, not many know the fascinating story behind it. The history of “Lunch Atop A Skyscraper” is shrouded in mystery, with questions lingering about its photographer, numerous tributes to the original, and even doubts about its authenticity.

The Setting For “Lunch Atop A Skyscraper”

surrounding “Lunch Atop A Skyscraper” is that it was taken atop the Empire State Building. However, the truth is that the photograph was actually captured during the construction of Rockefeller Center.

At 850 feet above the city streets, Rockefeller Center was a massive project launched in 1931. This iconic building, now a symbol of New York City, was not only impressive in its size but also had a significant economic impact during the Great Depression.

Christine Roussel, an archivist at Rockefeller Center, reveals that the construction project employed approximately 250,000 workers at a time when jobs were scarce due to the economic downturn. This fact sheds light on the immense scale and importance of the project during such challenging times.

Working on the construction of skyscrapers during the early 20th century came with its risks. Laborers had to toil hundreds of feet above the ground, often with minimal safety precautions. As John Rasenberger, author of High Steel: The Daring Men Who Built the World’s Greatest Skyline, started:

“The pay was good. The thing was, you had to be willing to die.”

That notion is vividly captured in photographs taken atop Rockefeller Center during its construction, including the iconic “Lunch Atop A Skyscraper.” These images portray workers balancing precariously on the skeleton of a skyscraper, their daily tasks resembling death-defying feats rather than ordinary 9-to-5 jobs.

Reveal the identity of the ironworkers

A New York Post survey revealed numerous claims regarding the identities of the men captured in the iconic photograph.

In 2012, the documentary Men at Lunch delved into these claims that two of the men were Irish immigrants. The director reported in 2013 that he planned to investigate claims made by Swedish relatives.

The film successfully confirmed the identities of two men, Joseph Eckner and Joe Curtis, by comparing the photograph with other pictures taken the same day, where they were named. Additionally, the first man from the right, holding a bottle, was identified as Slovak worker Gustáv (Gusti) Popovič.

Interestingly, the photograph was discovered in Popovič’s estate, with the note “Don’t you worry, my dear Mariška, as you can see I’m still with the bottle” written on the back. This intriguing detail adds depth to the story behind the photograph, offering a glimpse into the lives and personalities of the men captured in this timeless image.

Regarded as the “most famous picture of a lunch break in New York history” by Ashley Cross, a correspondent of the New York Post, the photograph has left an indelible mark on the city’s cultural landscape. Despite some critics dismissing it as a mere publicity stunt, Ken Johnston, manager of the historic collections of Corbis, called it “a piece of American history.”

Taken during the Great Depression, the photograph quickly became a symbol of New York City. It has since been recreated by construction workers, paying homage to its enduring significance. Time Magazine recognized its impact by including it in its esteemed list of the 100 most influential images in 2016.

When it comes to the image’s importance in 2012, Ken Johnston, manager of the historic collections of Corbis, highlighted its striking contrast. The scene of workers casually enjoying lunch amidst the dizzying heights of 800 feet in the air captivates viewers. The juxtaposition of the mundane act of lunch with the extraordinary setting of skyscraper construction creates a sense of awe and wonder.

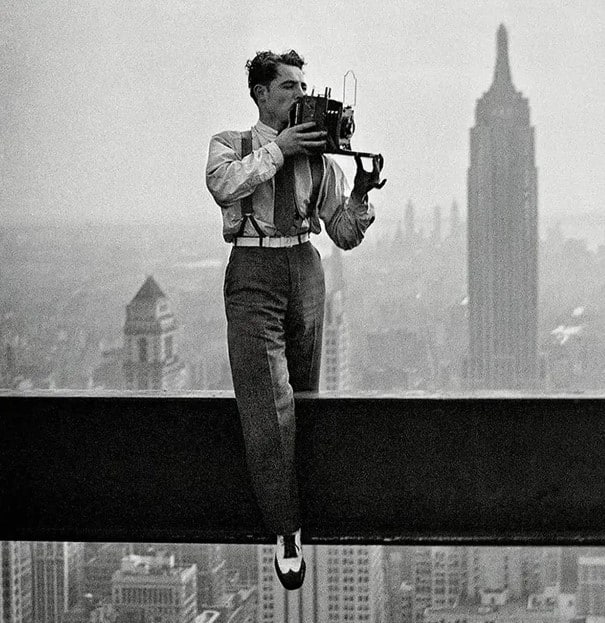

Who captured this iconic photo?

The identity of the photographer is still a mystery. Many mistakenly attributed the photograph to Lewis Hine, a photographer for the Works Progress Administration, due to the erroneous belief that the building in the image was the Empire State Building.

In 1998, Tami Ebbets Hahn, a resident of Wilmington, North Carolina, stumbled upon a poster of the iconic image. Intrigued, she speculated that it might be one of her father’s photographs. Her father, Charles C. Ebbets, who lived from 1905 to 1978, was a photographer. In 2003, Tami reached out to Ken Johnston of Corbis, seeking answers and hoping to unravel the mystery behind the photograph’s origins.

Corbis, a company that provides archived images to professional photographers, hired Marksmen Inc., a private investigation firm, to find who the owner of the photo is. During their search, an investigator found an article in The Washington Post crediting the image to Hamilton Wright.

Surprisingly, the Wright family did not recognize the photograph. It turns out that it was typical for Wright to be credited for photos taken by his employees. Interestingly, Hahn’s father was employed by the Hamilton Wright Features syndicate, suggesting a possible connection to the photograph’s origin.

In 1932, Ebbets was put in charge of photography for Rockefeller Center, tasked with promoting the new skyscraper. Hahn discovered her father’s paycheck of $1.50 per hour from that time, the famous ironworkers photo, and a picture of her father with a camera, all suggesting his involvement.

Johnston analyzed the evidence and concluded, “He’s the photographer.” Corbis eventually acknowledged Ebbets as the photographer. However, it was later found that other photographers, Thomas Kelley and William Leftwich, were also present that day. Due to the uncertain identity of the photographer, the image is again without credit.