5 Daring Escapes From Slavery That Have Left An Indelible Mark On History

Throughout history, enslaved individuals have demonstrated extraordinary courage and ingenuity in their quests for freedom.

These daring escapes not only highlight the relentless pursuit of liberty but also the incredible lengths to which people went to break the chains of bondage. From disguises and covert operations to perilous journeys, they are sure to make your heart beat faster.

Keep scrolling down to check out five remarkable tales of daring escapes from slavery now!

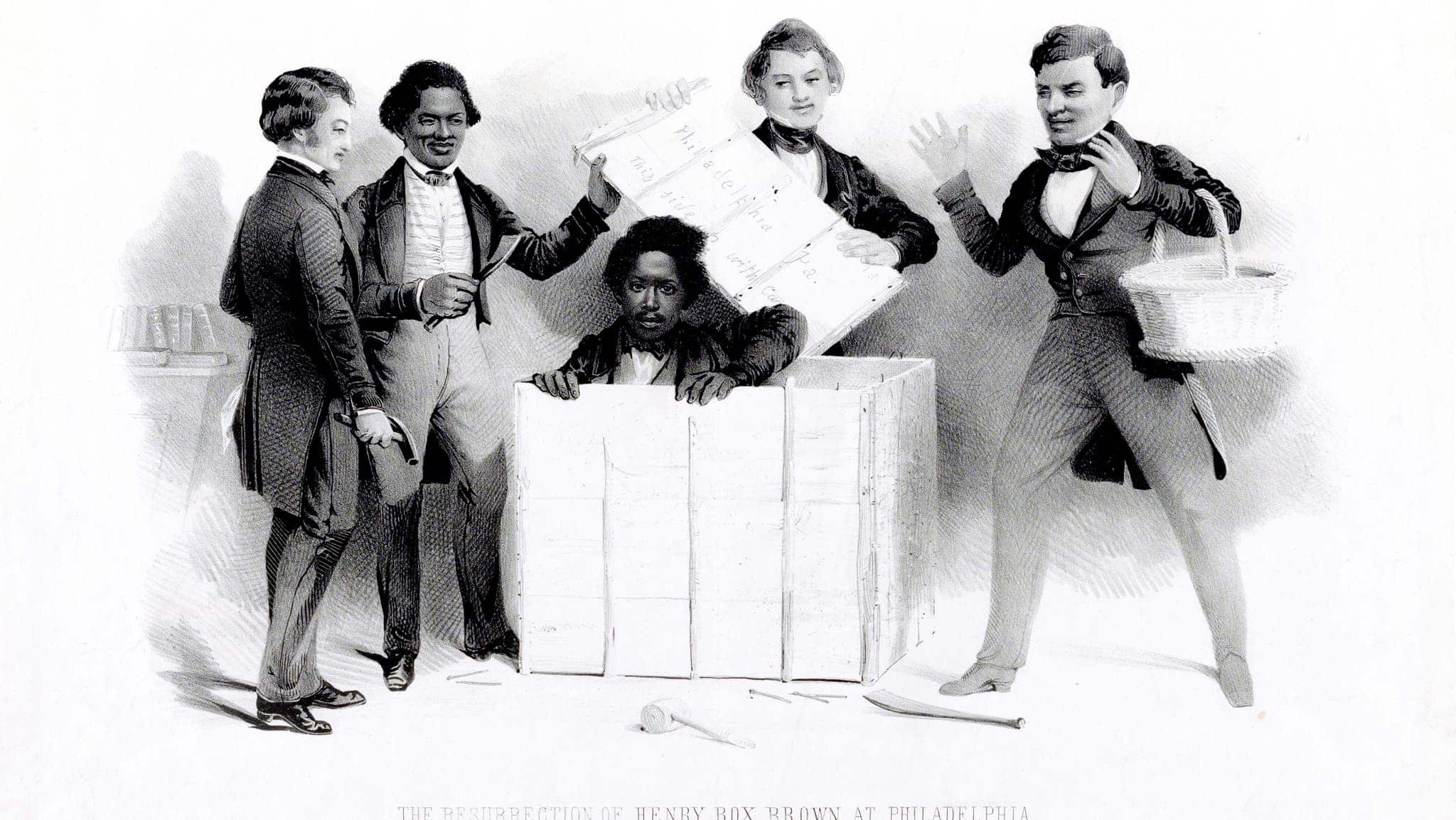

1. Henry ‘Box’ Brown

Henry Brown was born in Virginia. In 1848, his wife and children were sold and shipped to another state. Determined to escape slavery, Brown devised a daring plan. He decided to ship himself from Richmond to Philadelphia in a wooden crate, with the help of a free black man and a white shopkeeper.

On March 23, 1849, Brown squeezed himself into a small box measuring three feet by two feet. The box was labeled “dry goods” and would travel by wagon, steamboat, and railroad to the home of abolitionist James Miller McKim. Brown brought only a few biscuits and some water for the journey.

At one point, his crate was turned upside down on a steamship, leaving him sitting on his head for 90 minutes. The pressure caused his eyes to swell painfully, and he nearly lost consciousness. Fortunately, two passengers unknowingly set the box upright to use it as a seat.

After 27 exhausting hours, Brown arrived safely in Philadelphia. His incredible escape made him a minor celebrity in New England. However, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 forced him to flee the country.

“Box” Brown spent several years in Great Britain, where he performed a stage act recounting his escape. He eventually returned to the United States in 1875 and became a magician. In his shows, he would climb into the same wooden crate that had once carried him to freedom.

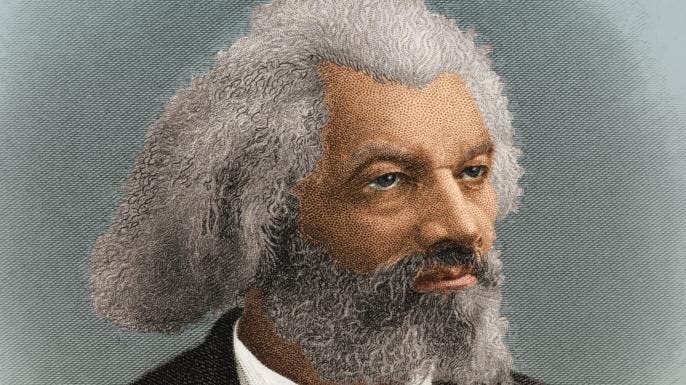

2. Frederick Douglass

In September 1838, 20-year-old Frederick Douglass, an enslaved man working as a ship’s caulker in Baltimore, decided to escape. He disguised himself in a sailor’s uniform his future wife, Anna Murray, gave him, and carried a free sailor’s protection pass borrowed from a friend, Douglass boarded a train heading north.

He hoped the papers would secure his freedom, but he knew they were risky because he looked nothing like the man listed in the documents. When the conductor came to check the black passengers’ papers, Douglass was filled with fear. “My whole future depended upon the decision of this conductor,” he later wrote. Fortunately, the conductor only gave the papers a quick look and moved on.

Douglass faced more dangerous moments as he continued his journey by train and ferry. On a riverboat, he saw an old acquaintance and narrowly avoided being recognized by a ship captain he had worked for before.

After several nerve-wracking hours, Douglass reached New York. There, he hid in the home of an anti-slavery activist and reunited with Murray. The couple then moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where Douglass became a leading abolitionist. He lived as a fugitive until 1846, when supporters helped him buy his freedom from his former master.

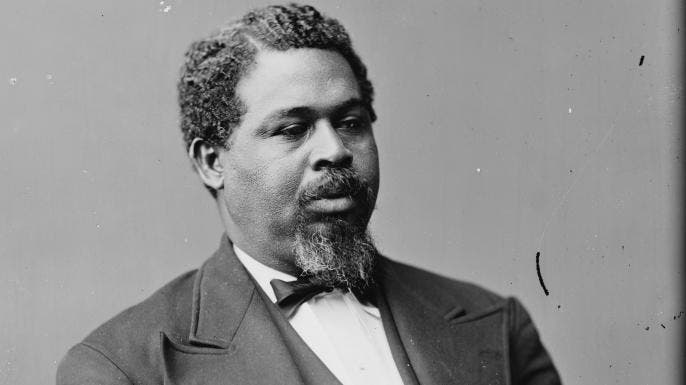

3. Robert Smalls

Robert Smalls was born into slavery in Beaufort, South Carolina. In 1862, during the American Civil War, he decided to free himself, his crew, and their family while he was working as a wheelman on the Confederate steamer CSS Planter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina.

In the early hours of May 13, the Planter’s white crew took unauthorized shore leave, giving Smalls and several accomplices their chance. They seized the ship and picked up their families at a prearranged spot.

Smalls, disguised in the captain’s coat and hat, steered the ship into Charleston Harbor. He knew the ship and the mine-filled harbor well, giving the correct signals to pass safely by Fort Sumter. Once out of range of the Confederate guns, he sped towards the Union blockade.

Under a white flag of surrender, Smalls and his crew offered their ship to the first U.S. Navy vessel they saw. “Good morning, sir!” Smalls called to the surprised captain. “I have brought you some of the old United States’ guns, sir!”

Smalls and his fellow escapees were celebrated as heroes in the North. Their bravery and skill showed that black men could be excellent soldiers. Smalls helped recruit up to 5,000 black men for the Union army and served as the pilot, and later the captain, of the Planter after it was converted into a U.S. Navy ship.

After the war, Smalls returned to South Carolina, bought his former master’s house, and served several terms in the U.S. House of Representatives.

4. Harriet Jacobs

Harriet Jacobs was born into slavery in Edenton, North Carolina. There, she was sexually harassed by her cruel enslaver, who refused to let her marry. Even after Jacobs had two children by another man, the harassment continued. When her master threatened to sell her children if she did not submit to his desire, she decided to seek freedom.

In 1835, she fled her plantation and hid in friends’ houses. Realizing her chances of reaching the North were slim, she eventually took refuge in a tiny attic crawlspace in her grandmother’s home.

The space was rat-infested and only nine feet long and seven feet wide, with a sloping ceiling that never reached higher than three feet. Jacobs described it as offering “no admission for either light or air.”

Despite these harsh conditions, she spent seven years in this coffin-like room, watching her children play outside through a small peephole and only leaving for short periods at night for exercise.

In 1842, Jacobs finally escaped to the North with the help of a friend who secured her passage on a boat to Philadelphia. From there, she traveled by train to New York and reunited with her family. She worked in New York and Boston for several years, always fearing capture by her former master.

Eventually, friends helped arrange for her purchase and manumission. Jacobs went on to become a prominent abolitionist and published a powerful account of her experiences titled “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.”

5. William and Ellen Craft

In 1848, William and Ellen Craft executed one of the most creative and daring escapes from slavery. The couple got married in Macon, Georgia, in 1846. They were enslaved by different masters and feared being separated.

They devised a clever plan to flee to Philadelphia. Ellen, who had light skin, cut her hair short, dressed in men’s clothing, and wrapped her head in bandages to disguise herself as an injured white man. William posed as her loyal black servant.

On December 21, 1848, they wore their disguises and boarded a train heading North. Their plan nearly failed at the start when Ellen ended up sitting next to a close friend of her master. However, her disguise worked, and she wasn’t recognized.

The Crafts traveled for several days by train and steamer, staying in fine hotels and mingling with upper-class whites to keep up their cover. Since Ellen couldn’t read or write, she pretended her arm was injured to avoid signing tickets and papers.

Their ruse was almost discovered when a clerk in Charleston demanded a signature before selling them tickets. Fortunately, the captain of their previous ship happened to be nearby and signed for her.

The Crafts arrived in Philadelphia on Christmas Day and were taken in by abolitionists. They continued to Boston but later sailed to England to avoid capture. In England, they wrote a popular account of their escape and started a family.