Examine Key Facts About The D-Day Invasion That Marked Turning Point In WWII

On June 6, 1944, the Allies launched a major operation called Neptune or Overlord, which is better known as D-Day. This mission, aiming to liberate Western Europe from German occupation during WWII, was one of the largest military efforts ever.

The success of D-Day was crucial for the Allies to defeat Nazi forces in Europe. Over 156,000 American, British, and Canadian troops landed on 50 miles of heavily defended beaches in northern France.

The D-Day invasion required careful planning and extraordinary courage, making it a decisive moment in the fight for freedom during World War II. Below are some important details about the epic Allied invasion’s preparation and execution.

The D-Day invasion required years of detailed planning.

Although planning for a European invasion started after the Dunkirk evacuation in 1940, detailed preparations for Operation Overlord, or D-Day, began after the Tehran Conference in late 1943.

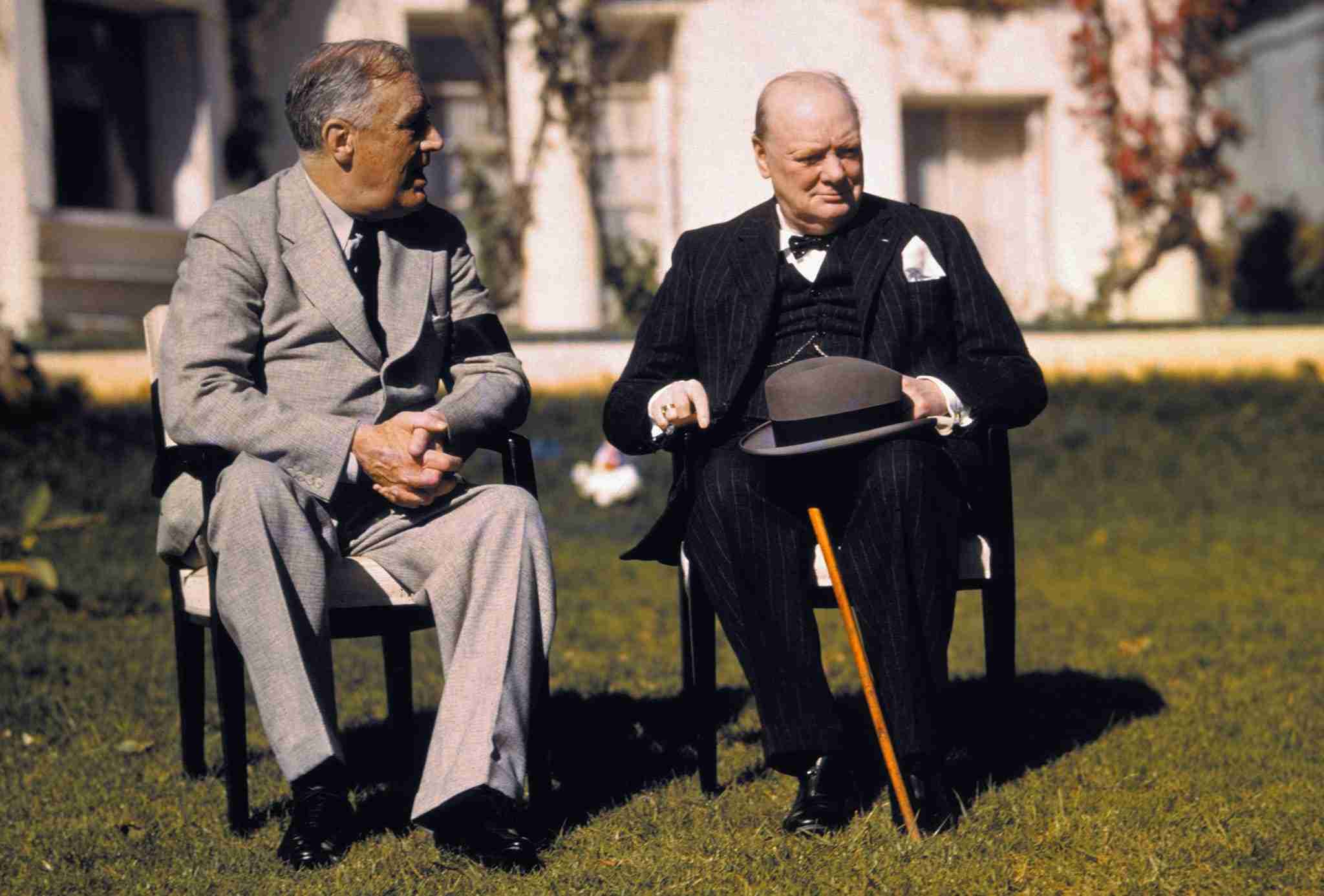

Allied leaders Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill knew a massive invasion of mainland Europe was essential to relieve pressure on the Soviet army fighting the Nazis in the East.

Initially, a plan called Operation Sledgehammer aimed to invade northwest France in 1943, but instead, they chose to invade Northern Africa and then Italy. Through these campaigns, the troops gained valuable amphibious warfare experience.

At the Trident Conference in May 1943, the decision was made to launch a cross-channel invasion within a year. While Churchill preferred an invasion through the Mediterranean, the Americans, who supplied most of the men and equipment, decided otherwise.

British Lieutenant-General Frederick E. Morgan was appointed Chief of Staff to start detailed planning. The lack of landing craft, mostly committed in the Mediterranean and Pacific, constrained initial plans.

Lessons from the failed Dieppe Raid in 1942 led the Allies to avoid heavily defended ports for their first landing. They focused on locations within the operating range of British aircraft for essential air support.

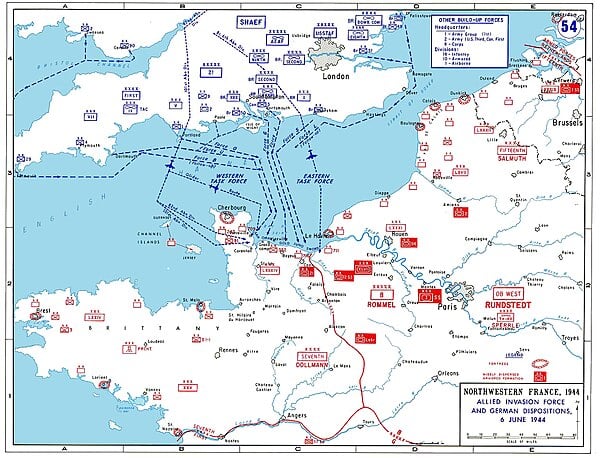

Normandy, with its broad front, allowed multiple attack points and was chosen despite its lack of port facilities, which would be addressed with artificial harbors.

The COSSAC staff initially planned the invasion for May 1, 1944, which was approved at the Quebec Conference in August 1943.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower was appointed commander of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, and General Bernard Montgomery was named commander of the 21st Army Group.

They expanded the invasion to five divisions with airborne support, which required more landing craft and delayed the invasion to June 1944. Ultimately, the Allies committed 39 divisions, totaling over a million troops, to the Battle of Normandy.

Allied forces executed a massive deception campaign beforehand.

The Allies wanted to trick the Nazis into thinking the invasion would happen at Pas-de-Calais, the closest French coast to England. They used fake radio messages, double agents, and even a “phantom army” led by General George Patton to confuse Germany.

Under Operation Bodyguard, several smaller operations were designed to mislead the Germans about the invasion’s date and place.

Operation Fortitude included two parts: Fortitude North used fake radio traffic to suggest an attack on Norway, while Fortitude South created a fake First United States Army Group under Patton, supposedly in Kent and Sussex.

This deception aimed to make the Germans believe the main attack would be at Calais. Real messages from the 21st Army Group were routed through Kent to further this illusion.

The Germans thought they had many spies in the UK, but all had been captured, and some were working as double agents for the Allies.

One such agent, Juan Pujol García, code-named “Garbo,” built a fake network of informants that fed the Germans false information. Before D-Day, he sent many messages to make them think the attack would be in July at Calais.

Many German radar stations on the French coast were destroyed before the landings. The night before D-Day, Special Air Service operators dropped dummy paratroopers over Le Havre and Isigny, misleading the Germans about additional airborne landings.

In Operation Taxable, RAF Squadron 617 dropped metal strips that fooled German radar into thinking a naval convoy was near Le Havre. A similar trick was used near Boulogne-sur-Mer by RAF Squadron 218 in Operation Glimmer.

It was an international effort and remains the largest amphibious invasion in history.

According to the D-Day Center, Operation Overlord, known as the D-Day invasion, involved 156,115 U.S., British, and Canadian troops. They used 6,939 ships and landing vessels, 2,395 aircraft, and 867 gliders to deliver airborne troops.

D-Day required unprecedented international cooperation. The Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) united the Allies against Germany but had to navigate political, cultural, and personal tensions.

By 1944, over 2 million troops from more than 12 countries were in Britain preparing for the invasion.

On D-Day, the primary forces were American, British, and Canadian, but also included support from Australian, Belgian, Czech, Dutch, French, Greek, New Zealand, Norwegian, Rhodesian, and Polish naval, air, or ground units.

The U.S. transported tons of supplies to the staging area in England.

To prepare for the invasion, British factories ramped up production. In the first half of 1944, about 7 million tons of supplies, including 450,000 tons of ammunition, were shipped from North America to Britain.

A significant Canadian force had been gathering in Britain since December 1939. Additionally, over 1.4 million American servicemen arrived in 1943 and 1944 to join the landings.

A dress rehearsal for D-Day was disastrous.

Two months before D-Day, the Allies held a practice invasion on Slapton Sands, an evacuated English beach.

This rehearsal, called Exercise Tiger, turned tragic on April 27, 1944, when a friendly fire incident killed about 450 men. Later, German E-boats attacked and sank American tank landing ships, resulting in 749 more deaths.

Survivors found this event more terrifying than the actual D-Day landings. “In comparison to the E-boat attack, Utah Beach was a walk in the park,” Steve Stadlon told NBC News in 2009.

Other training exercises with landing craft and live ammunition took place in Scotland, Northern Ireland, and London. Paratroopers also practiced large drops, including one on March 23, 1944, watched by Churchill, Eisenhower, and other leaders.

The U.S. military acknowledged the losses of Exercise Tiger after D-Day, but the story was overshadowed by the larger invasion and remains less known today.

Germany had heavily fortified the French coast with extensive defenses.

In November 1943, expecting an Allied invasion along the French coast, Adolf Hitler tasked Field Marshal Erwin Rommel with strengthening Nazi defenses in France.

Rommel completed the “Atlantic Wall,” a 2,400-mile line of bunkers, landmines, and obstacles from the Netherlands to Cherbourg. The Nazis planted an estimated 4 million landmines along Normandy’s beaches.

Hitler envisioned 15,000 emplacements manned by 300,000 troops, but shortages of concrete and manpower meant most were never built. The Pas de Calais was heavily fortified as the expected invasion site, while in Normandy, the best defenses were at Cherbourg and Saint-Malo.

Rommel suspected Normandy as a possible landing point, so he ordered extensive defenses there. These included concrete gun emplacements, wooden stakes, metal tripods, mines, and anti-tank obstacles to slow down landing craft and tanks.

He expected the Allies to land at high tide, so many obstacles were placed at the high tide mark. Barbed wire, booby traps, and the removal of ground cover made the approach hazardous for infantry.

Rommel also tripled the number of mines along the coast. Due to Allied air superiority, he installed booby-trapped stakes known as “Rommel’s asparagus” in fields to deter airborne landings.

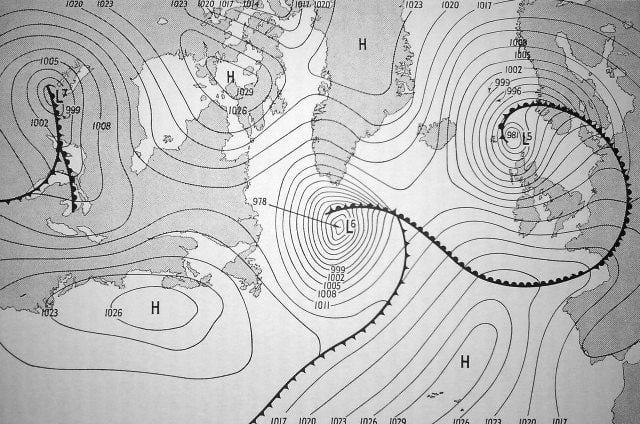

Bad weather postponed the invasion.

Eisenhower initially set June 5, 1944, for the invasion, but bad weather on June 4 made landing and air operations impossible. The storm forecast came from a weather station on Ireland’s western coast, prompting a 24-hour delay.

On the morning of June 5, after his meteorologist predicted better weather for the next day, Eisenhower approved Operation Overlord. He encouraged the troops, saying, “You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade. The eyes of the world are upon you.”

Later that day, over 5,000 ships and landing craft with troops and supplies left England for France. More than 11,000 aircraft were also mobilized to provide air cover and support for the invasion.

Paratroopers initiated the operation before dawn.

The D-Day invasion started early on June 6, as thousands of paratroopers landed on Utah and Sword beaches. Their goal was to block roads and destroy bridges to stop Nazi soldiers from getting reinforcements.

The American paratroopers at Utah beach faced tough conditions, with some drowning in marshes with their heavy gear and others shot down by Nazi snipers. Omaha Beach saw fierce fighting, with more than 2,000 American soldiers injured or killed.

Meanwhile, British and Canadian troops had an easier time at Sword Beach, quickly capturing two important bridges.

More than 156,000 Allied ground troops stormed the five beaches.

Thousands of landing ships arrived in waves. Over 156,000 Allied soldiers stormed five beaches in Normandy, facing roughly 50,000 German troops. Stormy seas disrupted the landings, throwing numerous troops off course.

At Omaha Beach, just two of the 29 tanks made it ashore on their own, with three more brought in later. American forces arrived at Utah Beach, including 14 Comanche “code-talkers” who communicated important information in their native language.

According to some estimates, the D-Day invasion resulted in more than 4,000 Allied casualties, with thousands more injured or missing.

By June 11, less than a week later, the beaches were secure, and over 326,000 troops, 50,000 vehicles, and 100,000 tons of equipment had landed in Normandy.

The hardest fighting occurred on Omaha Beach, while Canadian troops at Juno Beach captured the most territory.

At Omaha Beach, Allied air strikes didn’t knock out Nazi artillery bunkers. The first waves of American troops faced deadly German machine gun fire and mines on the beach.

Despite heavy losses, U.S. forces fought all day, pushing past a fortified seawall and up steep cliffs to finally silence the enemy guns by nightfall. All told, around 2,400 American soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing after the fierce battle at Omaha Beach.

Canadian troops at Juno Beach also suffered severe losses, battling through rough seas to land on a heavily defended shoreline.

Like their American counterparts, many Canadians were mowed down by enemy fire as they stormed the beach—initial estimates suggest a staggering 50 percent casualty rate.

Despite this, they pressed forward, driving the Germans back and capturing more towns and territory than any other units in Operation Overlord.

By June 11, all five beaches were secured by Allied forces.

Five days after the D-Day landing, troops swiftly set up two huge temporary harbors built over six months in England. Throughout the war’s remainder, these harbors handled around 2.5 million soldiers, 500,000 vehicles, and 4 million tons of supplies.

The Allies suffered at least 4,413 losses in Normandy, with total casualties in the prolonged battle reaching 226,000 by August.

By the month’s end, Allied forces had reached the Seine River, liberated Paris, and pushed German forces out of northwestern France, effectively ending the Normandy campaign.

The Allies then prepared to enter Germany, aligning with Soviet troops advancing from the east.

The Normandy invasion shifted momentum against the Nazis, dealing a significant psychological blow and preventing Hitler from reinforcing his Eastern Front against the advancing Soviets.

In spring 1945, on May 8, the Allies formally accepted Nazi Germany’s unconditional surrender, following Hitler’s suicide a week earlier on April 30.