Could You Believe This Russian Family Was Cut Off From All Human Contact For Over 40 Years?

Deep within the vast, frozen wilderness of Siberia, where the taiga stretches endlessly and few dare to tread, a remarkable discovery was made in 1978.

As a helicopter skimmed the treetops in search of a landing spot, its crew spotted something unexpected—a small clearing 6,000 feet up a mountainside, far from any known settlement.

What they found there was nothing short of astonishing: the Lykov family, isolated from all human contact for 40 years, surviving in a remote hut amidst one of Earth’s last true wildernesses.

How the Lykov family was found

Siberia, with its endless stretches of dense forests, steep mountains, and freezing cold, is a place where nature reigns supreme. Siberian summers are fleeting.

The snow clings to the landscape until May, and by September, the cold returns, locking the taiga in a frozen stillness. This vast wilderness stretches from Russia’s arctic reaches to Mongolia, east to the Pacific, and south to the Urals.

Here, the land is home to bears, wolves, and a few scattered human inhabitants, far removed from the modern world.

The taiga is inhospitable for most of the year; it would swallow those who dare to explore its depths. However, in the brief warmth of summer, it opens up, revealing its secrets to those who dare to look—from the sky.

In the summer of 1978, a helicopter skimming the treetops in the remote south of the Siberian forest made a startling discovery.

The crew was searching for a landing spot for a group of geologists when they spotted something unusual: a small clearing, 6,000 feet up a mountainside, far from any known settlement.

The clearing, with its long, dark furrows, suggested human activity—an impossibility in this unexplored, isolated area.

The discovery baffled the Soviet authorities, who had no records of anyone living in the area. Four scientists tasked with prospecting for iron ore were informed of the sighting.

The news worried them, as encounters with strangers in this part of the taiga could be more dangerous than crossing paths with wild animals. Nonetheless, curiosity prevailed, and they decided to investigate.

Led by geologist Galina Pismenskaya, the group set out to find the source of the mysterious clearing. As they climbed the mountain, they encountered signs of human presence: a rough path, a staff, a log bridge, and a small shed filled with dried potatoes.

Finally, they came upon a blackened hut, so camouflaged by the taiga’s debris that it was almost invisible. Yet, the tiny window indicated that people indeed lived there.

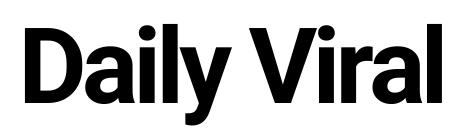

Their arrival was noticed. The hut’s low door creaked open, and an old man stepped into the daylight. His appearance was as if he had stepped out of a fairy tale—barefoot, with a beard and hair unkempt, wearing clothes patched together from sacking.

He seemed frightened yet attentive and unsure of the visitors standing before him.

“Greetings, grandfather! We’ve come to visit!” Pismenskaya called out, breaking the silence.

The old man did not respond immediately. When he finally spoke, his voice was soft and uncertain. “Well, since you have traveled this far, you might as well come in.”

The living conditions of the family

As the geologists entered the dimly lit cabin, they were met with a sight straight out of another era. The small, makeshift shelter was more like a burrow than a home.

It was described as “a low, soot-blackened log kennel that was as cold as a cellar,” with a floor covered in potato peels and pine-nut shells.

The space was cramped, musty, and indescribably filthy, supported by sagging beams that barely held the structure together.

Yet, astonishingly, this tiny, decrepit room was home to a family of five.

Sobs and lamentations of two women broke the silence inside the cabin. In the grip of hysteria, one of them began to pray aloud, “This is for our sins, our sins.”

The other woman, attempting to hide behind a post, slowly sank to the floor. The faint light from the small window fell on her wide, terrified eyes. The visitors that they had to leave the cabin immediately.

After some time, the old man and his daughters emerged, scared but curious. They refused the food offered to them, “We are not allowed that.” When asked if they had ever eaten bread, the old man replied, “I have. But they have not. They have never seen it.”

Why they moved into the faraway forest

Over time, as the geologists continued their visits, the remarkable story of the Lykov family began to unfold. The old man, Karp Lykov, was an Old Believer—a member of a strict Russian Orthodox sect that had clung to its 17th-century traditions despite centuries of persecution.

For Karp, history was still very much alive; he spoke of Peter the Great as if the Tsar were a personal enemy, calling him “the anti-Christ in human form” for his campaign to modernize Russia, which included the forced shaving of beards.

The Lykov family’s troubles deepened when the Bolsheviks came to power. Under Soviet rule, the persecution of Old Believers intensified, forcing many to flee deeper into the Siberian wilderness.

In the 1930s, after a Communist patrol shot Karp’s brother, Karp decided to take his family and vanish into the taiga.

That was in 1936, and at the time, the family consisted of Karp, his wife Akulina, their son Savin, and daughter Natalia. They carried what little they could—some possessions and seeds—and retreated into the forest, moving ever deeper with each passing year.

Two more children were born in the wild: Dmitry in 1940 and Agafia in 1943. Neither of the youngest Lykov children had ever seen another human being outside of their immediate family. Their knowledge of the outside world was limited to the stories their parents told.

According to the Russian journalist Vasily Peskov, who documented their story, the family’s main source of entertainment was “for everyone to recount their dreams.”

How they survived in the tundra

Surviving in the Siberian wilderness with two young children was challenging for the Lykov family. They relied on the few possessions they had brought with them, like pots, pans, and kettles, and foraged for food in the harsh environment.

Their meals primarily consisted of potatoes, rye, berries, and the occasional small animal they could catch.

When their shoes and clothing wore out, they made new ones from hemp and birch bark. They couldn’t protect themselves from the cold and wet, but it was all they had. Over time, even their essential equipment began to deteriorate.

Akulina, Karp’s wife, crafted new pots from dried-up bark and whatever natural materials she could find. However, they couldn’t replace their cooking pots without access to spare metal. And they just keep a small fire burning for warmth.

Their children, Dmitry and Agafia, were swaddled in hemp cloth and wore tiny birch bark shoes. Karp took on the role of teacher, showing his children how to find clean water, chop wood, and repair their hut.

In 1961, an unexpected June snowfall destroyed their crops, particularly their potatoes. With winter approaching and their food supply decimated, the Lykovs stared down the starvation barrel. Akulina chose to starve herself so that her children could have more to eat.

When the geologists discovered the family, they offered to help by taking them to a city where they could find modern comforts, but the Lykovs refused. Karp, having spent over 40 years in seclusion, was determined to remain in his cabin until the end.

The geologists gifted them essential items like salt, knives, forks, grain, pens, paper, and a torch and hoped to make their difficult lives a little easier.

Their life after discovery

In 1981, a terrible tragedy occurred when three of the Lykov children—Savin, Natalia, and Dmitry—died within days of each other. After their passing, Karp and his youngest daughter, Agafia, stayed in the cabin until Karp passed away in 1988.

After her father’s passing, Agafia stayed at the family cabin and tended to their goats and crops.

She made only five rare visits to the surrounding cities, either for medical care or to see relatives, but each time, she returned to the place she called home—now famously known as the Lykov territory.

The story of the Lykov family garnered widespread attention in Russian media, and with the advent of the internet, it reached a global audience.

In 2016, Agafia had to be airlifted from her cabin to a hospital for medical treatment. Once discharged, she insisted on returning to her secluded life in the Siberian wilderness.

As of 2024, Agafia Lykov, now 80 years old, continues to live in the cabin her father built in 1936 after fleeing religious persecution.

When asked about her thoughts on modern life, Agafia remarked that there were “too many people” and “too many cars,” and that the air in cities was difficult to breathe due to the pollution.

It seems likely that Agafia will remain in her beloved cabin, deeply connected to the wilderness, until her final days.