Carcassonne: A French Fortified City That Dates Back To At Least 200 B.C.

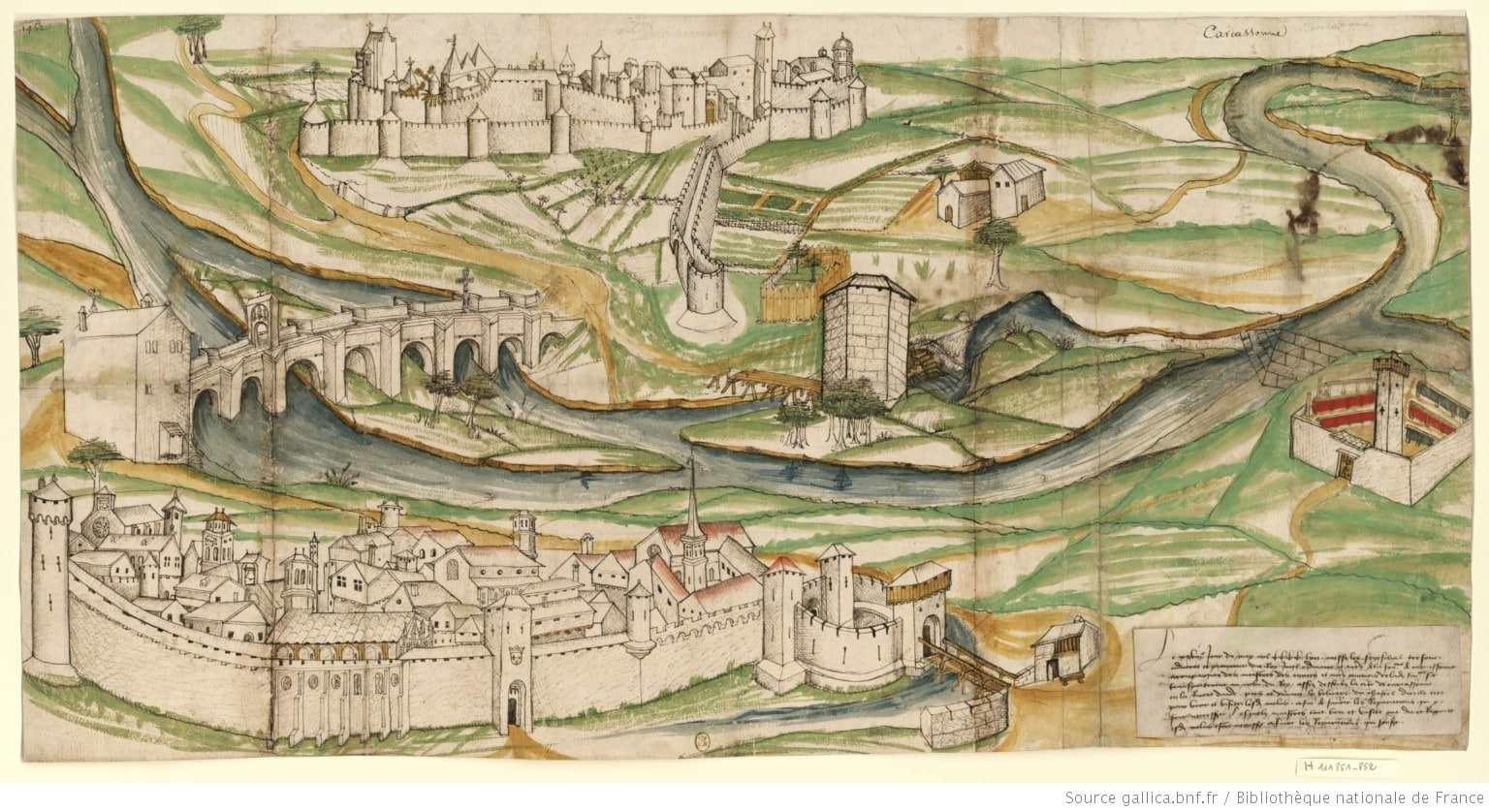

Carcassonne is a captivating French fortified city in the department of Aude, region of Occitania.

This citadel dates back to at least 200 B.C. and was known for its medieval fortress, the Cité de Carcassonne.

In the Middle Ages, Carcassonne was a bustling hub for commerce and trade with the Middle East.

Its wealth and prosperity made it an attractive target for invaders.

A Glimpse into Ancient Times

Carcassonne’s history dates back to the Neolithic era, about 200 B.C.

Its location in the Aude plain made it a crucial trade hub, connecting the Atlantic to the Mediterranean and the Massif Central to the Pyrénées.

This strategic significance was recognized by the Ancient Romans, who fortified the hilltop around 100 BC, transforming it into the colonia of Julia Carsaco, later known as Carcaso and eventually Carcasum.

Remnants of these Gallo-Roman fortifications are still visible today.

The Rise of the Visigothic Kingdom

In the fifth century, the region of Septimania, including Carcassonne, fell under the control of the Visigoths, who established the city as part of their kingdom.

The Visigothic king Theodoric II, who had held Carcassonne since AD 453, built additional fortifications, reinforcing the city as a frontier post.

This period also saw the beginnings of the Basilica of Saint Nazaire, a predecessor of the current basilica dedicated to the same saint.

The Medieval Stronghold

In the 11th century, the Trencavel family took control of Carcassonne, building significant structures like the Château Comtal and the Basilica of Saints Nazarius and Celsus.

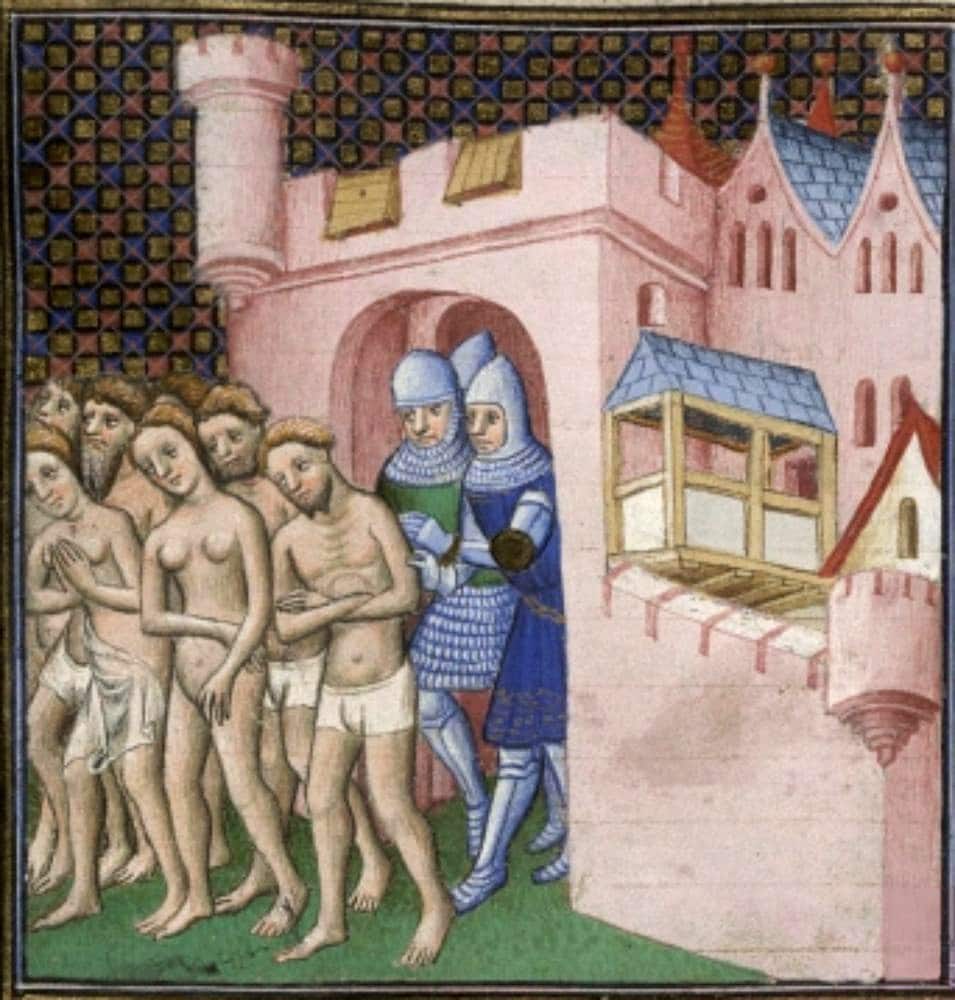

The city played a key role in the Albigensian Crusades of the early 13th century as a Cathar stronghold.

After a siege by the Papal Legate’s army, the city surrendered, leading to a change in leadership and further fortifications.

The French Connection and Fortification

In the 13th century, Carcassonne became part of the French royal domain.

King Louis IX and his successor Philip III strengthened its defenses with double outer walls, 53 towers, and barbicans, making it nearly impregnable.

Despite attacks during the Hundred Years’ War, Carcassonne remained resilient, with its strategic importance recognized even into the early modern period.

Decline and Restoration

The Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659 diminished Carcassonne’s military significance, leading to a period of economic focus, particularly in the woollen textile industry.

By the 19th century, the fortress was in disrepair, and the French government considered demolishing it.

However, a campaign led by antiquary Jean-Pierre Cros-Mayrevieille and writer Prosper Mérimée saved the fortress, leading to its restoration by architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc.

Viollet-le-Duc’s Controversial Restoration

Viollet-le-Duc’s restoration of Carcassonne, beginning in 1853, aimed to revive its medieval grandeur

His work, though controversial, restored the roofing of the towers and ramparts, consolidating the fortifications.

Despite some criticism for using slate instead of local terracotta tiles, Viollet-le-Duc preserved the city’s historical integrity.

His pupil, Paul Boeswillwald, continued the restoration after Viollet-le-Duc’s death.

The Modern-Day Carcassonne

Today, Carcassonne is a popular tourist destination, attracting visitors from around the world to its medieval fortress.

The Cité de Carcassonne, with its impressive double-walled fortifications and historic towers, stands as a symbol of the city’s enduring legacy.

The lower town, or ville basse, remains the city’s economic center, with roots dating back to the Late Middle Ages.

In 1997, Carcassonne was added to the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites because of its focal point of strategic importance since its inception.

The Gates of the Cité of Carcassonne

Carcassonne’s Cité, the medieval fortified city, originally had four main gates.

Each gate served a specific function in the city’s defense system:

1. The Narbonnaise Gate (Porte Narbonnaise)

This was the main entrance and the most important gate, leading into the city from the direction of Narbonne.

It features two massive towers and is one of the most iconic parts of the fortifications.

2. The Aude Gate (Porte d’Aude)

This gate is located on the southern side.

It provided access to the city from the direction of the Aude River.

It is also known as the “Porte de l’Aude.”

3. The Saint-Nazaire Gate (Porte Saint Nazaire)

Situated on the eastern side, this gate was named after the Basilica of Saint Nazaire, which is located nearby.

4. The Rodez Gate (Porte de Rodez)

This gate is also known as the “Porte d’Aude” or “Carcassonne Gate”.

It is located on the northern side of the city and serves as another major entrance into the Cité.

The Legend of Lady Carcas

The legend begins with the city of Carcassonne under siege by Charlemagne’s forces.

The city was ruled by Lady Carcas (or “La Dame Carcas” in French), who was the widow of a Saracen king.

When the defenders of the city were running out of food and hope, she devised a clever ruse to save the city.

She had her people gather all the remaining food and throw it over the city walls.

She also had the last remaining pig fed the last grains of wheat and then thrown over the walls. This made the besieging army believe the city had ample supplies.

Lady Carcas then instructed her people to light a large bonfire and create a great deal of noise to make it appear as though the city was still well-stocked and vibrant.

The enemy troops mistakenly believed that Carcassonne was still well-supplied and reinforced.

They thought that continuing the siege was futile and would be a waste of resources. As a result, they decided to withdraw.

In celebration, Lady Carcas is said to have climbed to the top of the city walls and rung the city bells to celebrate the retreat of the enemy.

The Origin of the City’s Name

The name “Carcassonne” is said to be derived from Lady Carcas’s name.

When Charlemagne’s forces left, the people of Carcassonne celebrated by naming the city after their courageous ruler.

The Old Streets of the Walled Town

The old streets of Carcassonne’s walled town are a charming maze of narrow, cobblestone paths.

These ancient streets are designed for defense, twist, and turn through the medieval city.

Many houses have timber frames and stone walls, with colorful shutters and wrought iron balconies.

The Place du Palais is a central square with historic buildings, while the Rue Trivalle is lined with medieval houses and shops.

The narrow lanes and tall buildings create a cozy, timeless feeling, often bustling with tourists and locals.

The Basilica of Saint Nazaire

The Basilica of Saint Nazaire in Carcassonne, originally a cathedral, has a rich history.

First mentioned in historical records in 925, it was officially consecrated by Pope Urban in 1096.

The basilica’s gothic structure was completed in the 12th century but has undergone several renovations since.

Architectural Highlights:

- Romanesque Portal: The north façade features a Romanesque portal with five arches and two doors, reflecting its early architectural style.

- Gothic Elements: The transept and choir display gothic architecture, contrasting with the Romanesque elements of the façade.

- Stained Glass: The basilica is renowned for its beautiful stained-glass windows, some of the finest in the Languedoc region, which add vibrant color and light to the interior.

The basilica lost its status as Carcassonne’s cathedral in 1801 when St. Michel Cathedral in the Lower Town took over.

However, in 1898, Pope Leo XIII elevated it to the status of a Basilica, recognizing its historical and spiritual importance.

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc restored its exterior in the 19th century, preserving its historical charm.

The Château Comtal

The Château Comtal, or Count’s Castle, is a fortress within a fortress.

The Château was built in the 12th century by the Trencavel family.

It was a central stronghold in the fortified city and featured a keep, a barbican, and a dry moat.

The castle provides insights into medieval military architecture and houses a museum with artifacts and exhibits detailing the history of Carcassonne.

It boasts thick walls and 24 towers, with a moat and drawbridge adding to its defensive strength.

Inside, you’ll find well-preserved medieval rooms, including the grand hall and the dungeon.

Inside the Château Comtal

Inside the castle, several fascinating artifacts are on display:

- Five Tombstones from the 14th Century: These tombstones provide a poignant connection to the medieval inhabitants of Carcassonne, offering insights into the funerary practices of the time.

- Old Keystones from the 13th Century: These keystones are intricately carved and offer a glimpse into the architectural details of the period.

- 12th-Century Ablution Fountain: This fountain, adorned with a decorative strip called “rinceau” and twelve mascarons, showcases the artistic craftsmanship of the time.

- Antique Marble Sarcophagi: These sarcophagi, made from marble, highlight the city’s Roman and early Christian heritage.

The hoardings

Hoardings, wooden structures that jut out from the walls, were used by defenders to drop projectiles or boiling oil on attackers below.

These reconstructions give visitors an idea of the defensive strategies employed during medieval sieges.

Hoardings provided a protected area for defenders to launch projectiles and pour boiling liquids on invaders.

The hoardings were added during the 19th century by Viollet-le-Duc.