Bodiam Castle: One Of England’s Most Photogenic, Romantic-Looking, Medieval Castles

Bodiam Castle is a 14th-century moated castle located near Robertsbridge in East Sussex, England.

It was built in 1385 by Sir Edward Dalyngrigge, a former knight who served Edward III.

The castle was to defend against potential French invasions during the Hundred Years’ War.

The Construction Of The Castle

Sir Edward Dalyngrigge, the castle’s builder, was a younger son who did not inherit his father’s estates.

As a result, he had to make his own fortune.

By 1378, he owned the manor of Bodiam through marriage into a land-owning family.

Dalyngrigge was a prominent figure in Sussex, serving as a Knight of the Shire and becoming one of the most influential people in the county.

He made his fortune by fighting as a mercenary in France during the Hundred Years’ War, returning to England in 1377.

In 1385, with renewed hostilities between England and France, Dalyngrigge was granted permission by King Richard II to fortify his manor house.

Instead of fortifying the existing house, he chose a new site to build Bodiam Castle, which was completed in one phase.

Why Was It Called Bodiam Castle?

Bodiam Castle was named after the nearby village of Bodiam in East Sussex, England.

The name “Bodiam” is believed to have originated from Old English, where “bod” could mean a dwelling or building, and “ham” means village or homestead.

Therefore, Bodiam roughly translates to the “homestead by the building.”

The castle took its name from the village because it was built on the manor of Bodiam, which Sir Edward Dalyngrigge acquired through marriage.

The Home of The Dalyngrigge Family

Bodiam Castle was passed down through the Dalyngrigge family.

After that, it was passed to the Lewknor family through marriage.

During the Wars of the Roses, Sir Thomas Lewknor, a member of the Lewknor family, supported the House of Lancaster.

When Richard III of the House of York became king in 1483, an army was sent to besiege Bodiam Castle.

It’s not clear if the siege actually took place, but it’s believed that the castle was surrendered without much resistance.

Although the castle was confiscated, it was later returned to the Lewknor family when Henry VII became king in 1485.

The Lewknor family owned the castle until at least the 16th century.

By the time of the English Civil War in 1641, Bodiam Castle was owned by Lord Thanet, who supported the Royalists.

He sold the castle to help pay fines imposed by Parliament. The castle was then partially dismantled and left as a picturesque ruin.

In 1829, John Fuller purchased the castle and began restoration work.

It was later sold to George Cubitt, 1st Baron Ashcombe, and then to Lord Curzon, both of whom continued the restoration efforts.

Bodiam Castle is now protected as a Grade I listed building and Scheduled Monument.

It has been owned by The National Trust since 1925, after being donated by Lord Curzon, and is open to the public.

Architecture of the castle

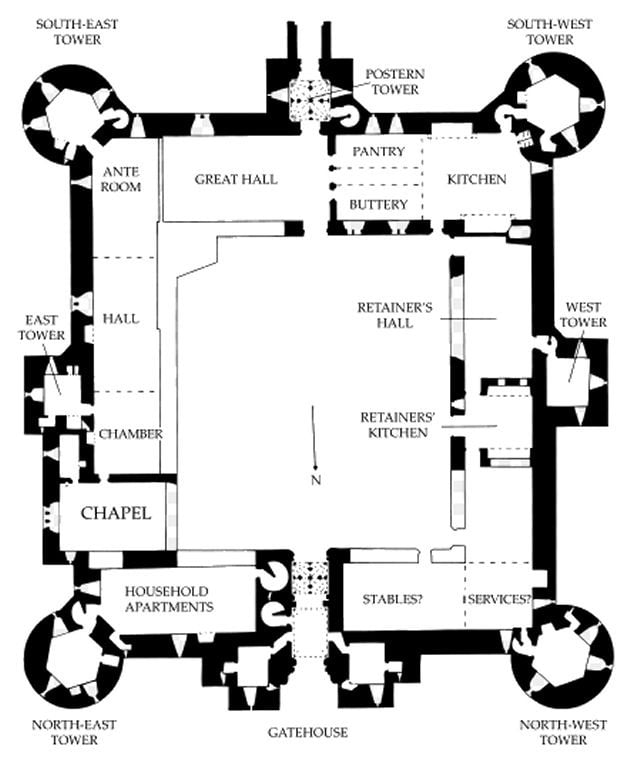

Bodiam Castle has a quadrangular design with strong, symmetrical design elements.

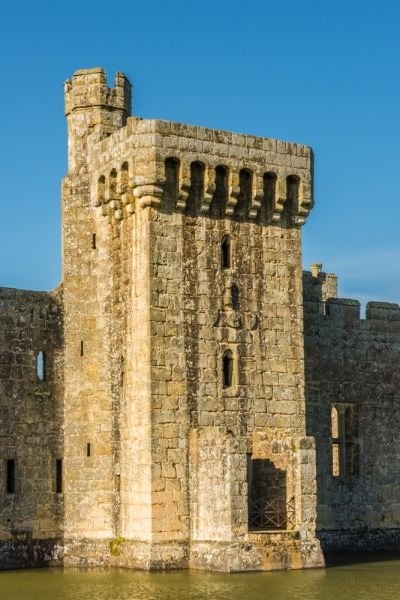

It is surrounded by a wide, water-filled moat, which adds an extra layer of protection.

Walls and Towers

The castle’s curtain walls are approximately 7 feet thick and rise to about 35 feet.

These walls are punctuated by four corner towers and two central gatehouses, one on the north side and one on the south.

The towers are cylindrical, which helped deflect projectiles during sieges.

Each tower has multiple levels, with arrow slits for archers and crenellations along the top for added defense.

The Postern Tower was a side entrance, likely used for bringing in goods across a drawbridge.

It once had a portcullis for added security.

During excavations inside the castle, a well was found in the basement of the southwest tower.

Gatehouse

The north gatehouse is the most fortified part of the castle and would have served as the main entrance.

It features a portcullis, heavy wooden doors, and murder holes—small openings in the ceiling through which defenders could drop rocks or pour boiling liquids on attackers.

The gatehouse is flanked by two round towers, further strengthening its defenses.

Machicolations

The castle’s walls and towers are adorned with machicolations—overhanging parapets with openings in the floor.

These allowed defenders to drop objects on attackers directly below, providing an additional line of defense.

Interior Layout

Much of the interior is now in ruins.

The castle has no central keep.

Instead, its various rooms are arranged along the outer defensive walls around an inner courtyard.

Back then, vegetables weren’t popular with the upper classes because they grew in the ground, so they were seen as food for peasants.

Because of this high demand, a special room was needed to store all the bread.