A Peaceful Night: How Christmas Stilled The Guns Of War

During World War I, Christmas brought unexpected moments of peace on the battlefield. The most famous was the “Christmas Truce” of 1914 when soldiers on the Western Front called a spontaneous ceasefire on Christmas Eve.

In the cold, muddy trenches, soldiers from both sides decided to stop fighting. They even ventured into no man’s land to share holiday greetings and small gifts. This brief pause in fighting even spread to some areas on the Eastern Front.

The truce remains one of the most fascinating and heartwarming episodes in wartime history.

Christmas carols in the trenches

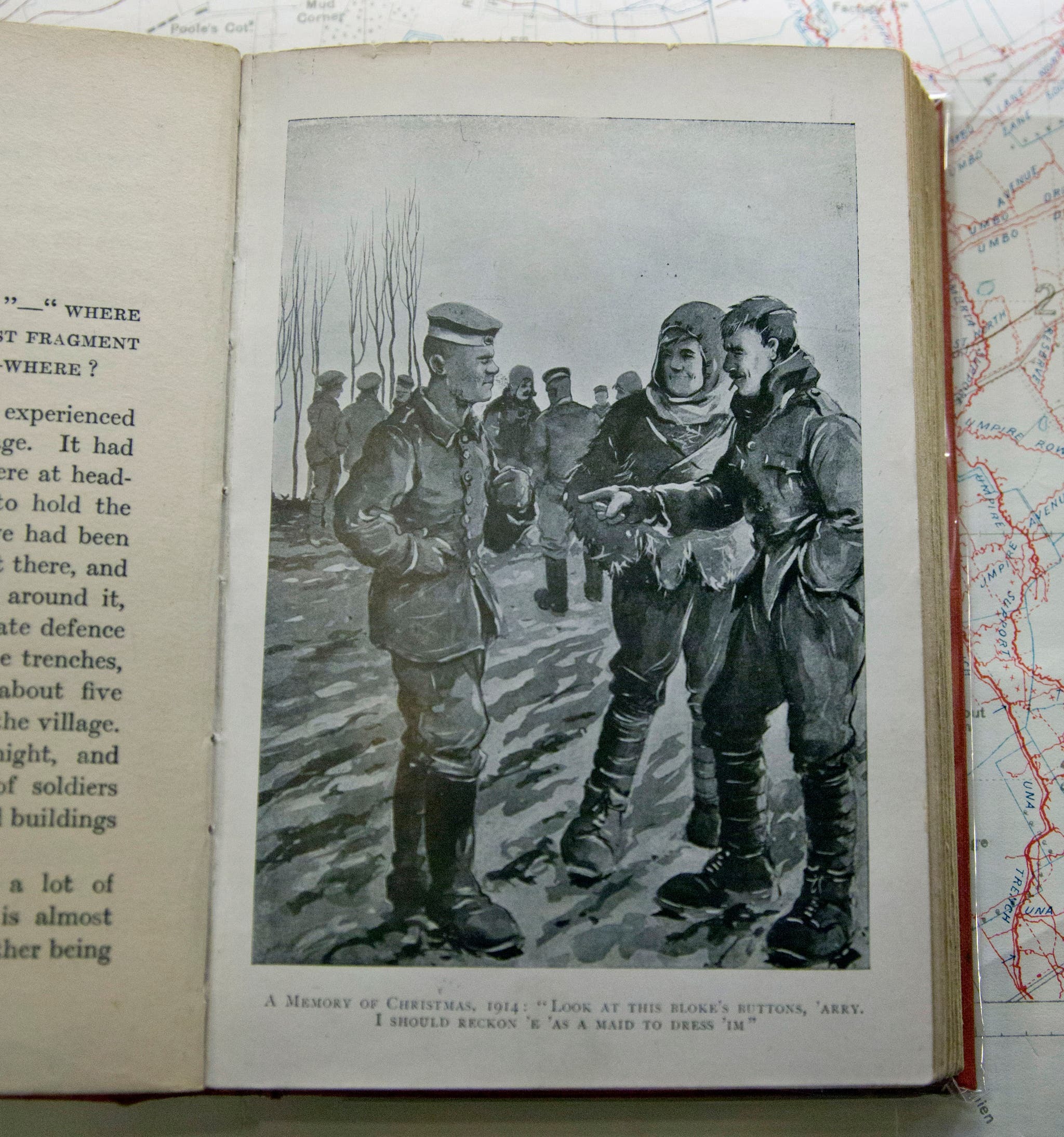

British machine gunner Bruce Bairnsfather, who later became a famous cartoonist, described the Christmas Eve truce in his memoirs.

Trapped in a cramped, muddy trench in Belgium’s Bois de Ploegsteert, Bairnsfather and his comrades endured the cold and discomfort of war, their days filled with fear and their nights sleepless.

Amidst the grim reality of trench life, he wrote, “Here I was, in this horrible clay cavity… miles and miles from home. Cold, wet through, and covered with mud.”

At around 10 p.m., Bairnsfather heard unusual noises. “Away across the field, among the dark shadows beyond, I could hear the murmur of voices.” He realized that the Germans were singing Christmas carols.

Suddenly, a German voice with a heavy accent called out in English, “Come over here.” A British sergeant replied, “You come half-way. I come half-way.” The interaction led to a spontaneous truce.

British and German soldiers meet

What happened next would stun the world and become a historic moment. Enemy soldiers nervously climbed out of their trenches and met in the barbed-wire-filled “No Man’s Land” between them.

Instead of firing shots, they exchanged handshakes and words of kindness. British and German troops traded songs, tobacco, and wine, creating an impromptu holiday celebration on the freezing night.

Bairnsfather was amazed by the scene. “Here they were—the actual, practical soldiers of the German army. There was not an atom of hate on either side.”

This unexpected truce wasn’t limited to one spot. On Christmas Eve, small groups of French, German, Belgian, and British troops engaged in spontaneous cease-fires across the Western Front, with some reports indicating similar events on the Eastern Front.

In some cases, these informal truces lasted for several days. For the soldiers, it was a welcome respite from the harsh realities of war.

When the war began just six months earlier, soldiers had hoped for a swift end and to be home for the holidays. Instead, the war continued for four more years, becoming the deadliest conflict of its time.

The Industrial Revolution had introduced powerful new weapons, and poor news from battles like Tannenberg and the Marne had devastated morale.

By winter 1914, the Western Front was a landscape of misery and death, making the Christmas truce a brief but cherished moment of peace.

Memories of the Christmas truce

Descriptions of the Christmas Truce can be found in many diaries and letters from the time. Rifleman J. Reading, a British soldier, wrote to his wife about his unique Christmas experience in 1914:

“My company was in the firing line on Christmas Eve, and I was assigned to stay in a ruined house until 6:30 Christmas morning. Early on, the Germans began singing and shouting in English, asking if we had a spare bottle and suggesting we meet halfway.”

Reading continued, “Later in the day, they approached us, and we went out to greet them. I shook hands with some German soldiers, and they gave us cigarettes and cigars. We didn’t fire that day; it was so peaceful it felt like a dream.”

Another British soldier, John Ferguson, reflected on the truce: “We were laughing and chatting with men we had been trying to kill just hours earlier!”

Diaries and letters also describe Germans setting up Christmas trees with candles around their trenches. One German soldier recounted a British soldier setting up a makeshift barbershop, charging Germans a few cigarettes per haircut.

Other accounts also recount scenes of men from both sides helping each other collect the dead amid the widespread devastation.

Soccer game during the truce

In an interview, British fighter Ernie Williams recounted a spontaneous soccer game during the truce, saying,

“The ball appeared from somewhere; I don’t know where. They made up some goals, and one fellow went in goal. It was just a general kick-about, with about a couple of hundred taking part.”

German Lieutenant Kurt Zehmisch, who spoke both English and German, also noted the game in his diary, discovered in 1999 near Leipzig.

He wrote, “Eventually, the English brought a soccer ball, and soon a lively game ensued. It was marvelously wonderful and strange. Christmas, the celebration of love, brought enemies together as friends for a time.”

News of the Christmas Truce slowly reached the press. A soldier wrote in The Irish Times on January 15, 1915, about “the most extraordinary celebration” he had ever experienced.

He described a scene with “officers and men, English and German, grouped around the bodies laid out in rows.” He noted that the Germans were “quite affable.”

The exact number of soldiers involved in these informal gatherings remains uncertain. A Time magazine story on the centennial suggested that up to 100,000 might have participated in these small-scale, haphazard, and unauthorized ceasefires.

Reactions to the Christmas ceasefire

Adolf Hitler, then just 25, criticized the Christmas Truce, remarking, “Such a thing should not happen in wartime. Have you no German sense of honor left?”

His disapproval echoed the broader sentiments of military leaders, who feared that the truce would undermine their troops’ resolve and disrupt the war effort.

The high command was resolutely against the truce. Pope Benedict XVI’s plea for a ceasefire had been ignored, and the spontaneous ceasefire angered the military leaders.

British General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien wrote in a confidential memo that the truce revealed a troubling apathy among the troops.

Orders were issued to halt any fraternization, with threats of court-martials for those who interacted with the enemy. Gradually, the war’s brutality resumed, with shots fired and efforts to drown out any future carol singing.

The 1914 Christmas Truce was a poignant moment when soldiers on both sides saw each other as fellow humans, longing for home and peace.

Historian Dan Snow noted that the truce was “a brief tantalizing flash of individual humanity in a war of bureaucracies, machines, and high explosives.” It allowed soldiers to connect as fathers, brothers, and sons rather than as faceless enemies.

While no further Christmas Truces occurred during World War I, the 1914 event inspired art, movies, and songs.

Today, a memorial in England’s National Memorial Arboretum, dedicated by Prince William, commemorates this historic moment. In 2014, the English and German soccer teams honored the truce with a friendly match, with England winning 1-0.

The soldiers’ own words remain lasting reminders. One British rifleman remembered a German soldier saying, “Today we have peace. Tomorrow you fight for your country. I fight for mine. Good luck!”