How The First Day Was After Sweden Changed Traffic Sides In 1967

On September 3, 1967, Sweden embarked on one of the most daring and complex traffic reforms in history, known as Dagen H. It was the day the nation switched from driving on the left-hand side of the road to the right.

The decision was met with widespread skepticism, but it ultimately reshaped Swedish roads, improved safety, and aligned the country with its European neighbors.

How did this monumental change unfold, and what did that first day look like? Let’s take a closer look.

Why Sweden Switched Sides

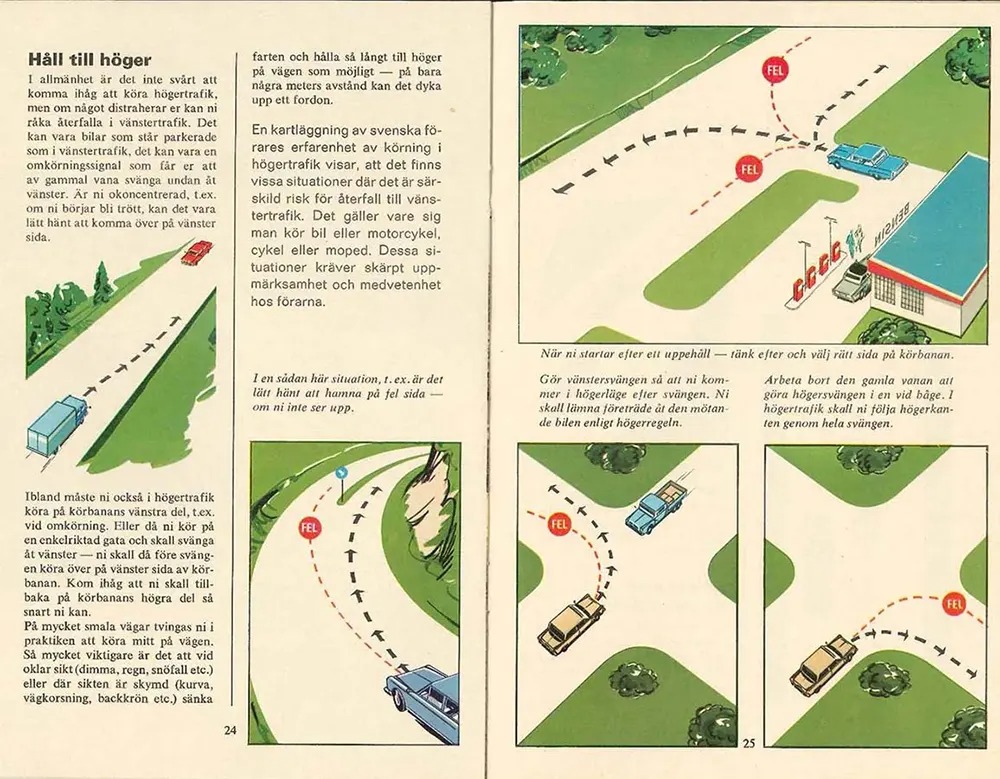

In the mid-20th century, Sweden faced a big problem with its roads. Even though cars drove on the left side, about 90% of vehicles were left-hand drive, mostly imported from the U.S. and Europe.

This made overtaking other cars risky and caused many accidents. Additionally, all of Sweden’s neighbors, like Norway and Finland, drove on the right side, making border crossings even more dangerous.

The decision to switch was not taken lightly. In fact, it was widely unpopular. A 1955 referendum showed that 83% of Swedes opposed the change.

However, with traffic fatalities rising and safety becoming a top priority, the Swedish government pressed forward. In 1963, the Riksdag officially passed the law to make the switch, giving the country four years to prepare.

Massive Efforts for a Smooth Transition

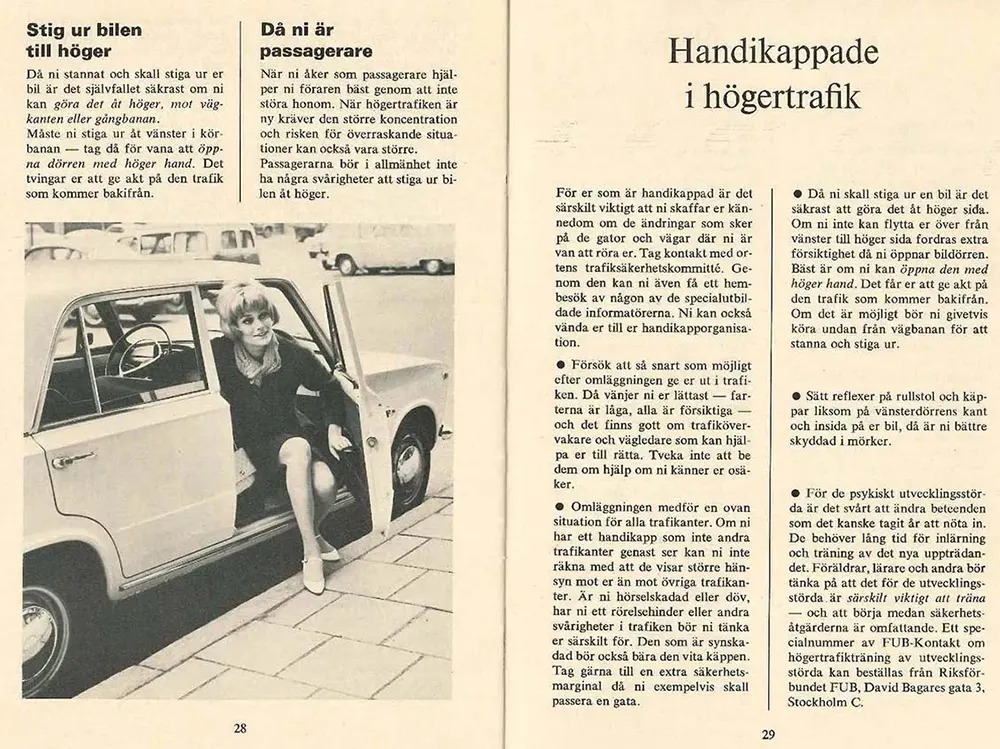

The Högertrafikkommission (HTK), the agency in charge of Sweden’s switch to right-hand driving, launched a massive public awareness campaign.

They went all out, with educational programs in schools and constant media coverage. The now-famous “Dagen H” logo was everywhere—from milk cartons to billboards.

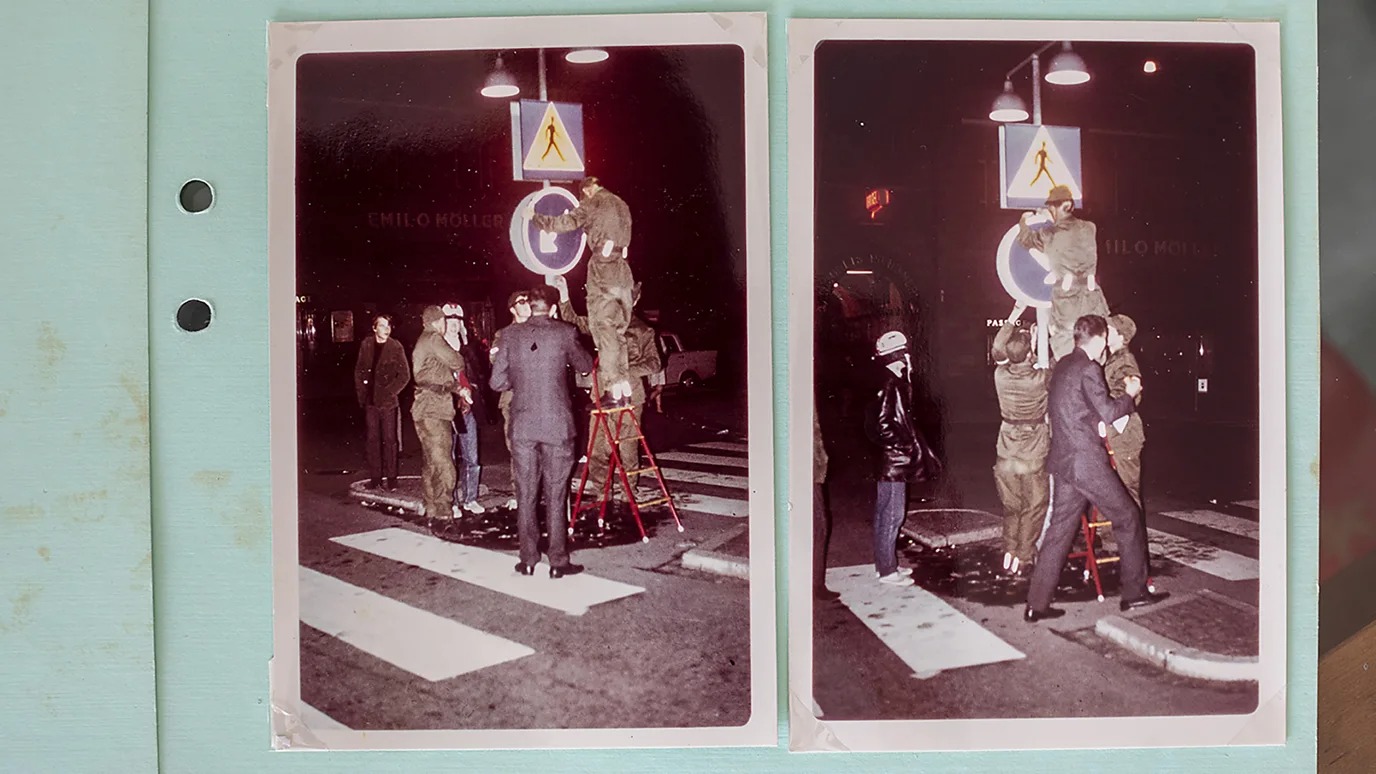

Changing the infrastructure was a huge task. In just one night, over 360,000 road signs were swapped, traffic lights were repositioned, and intersections were redesigned for the new traffic flow.

Major cities like Stockholm and Malmö even shut down their roads for nearly 24 hours to allow workers to reconfigure everything.

To make sure people didn’t forget, around 130,000 reminder signs were posted across Sweden, and most cars had a large “H” sticker on their dashboard as a constant reminder of the switch.

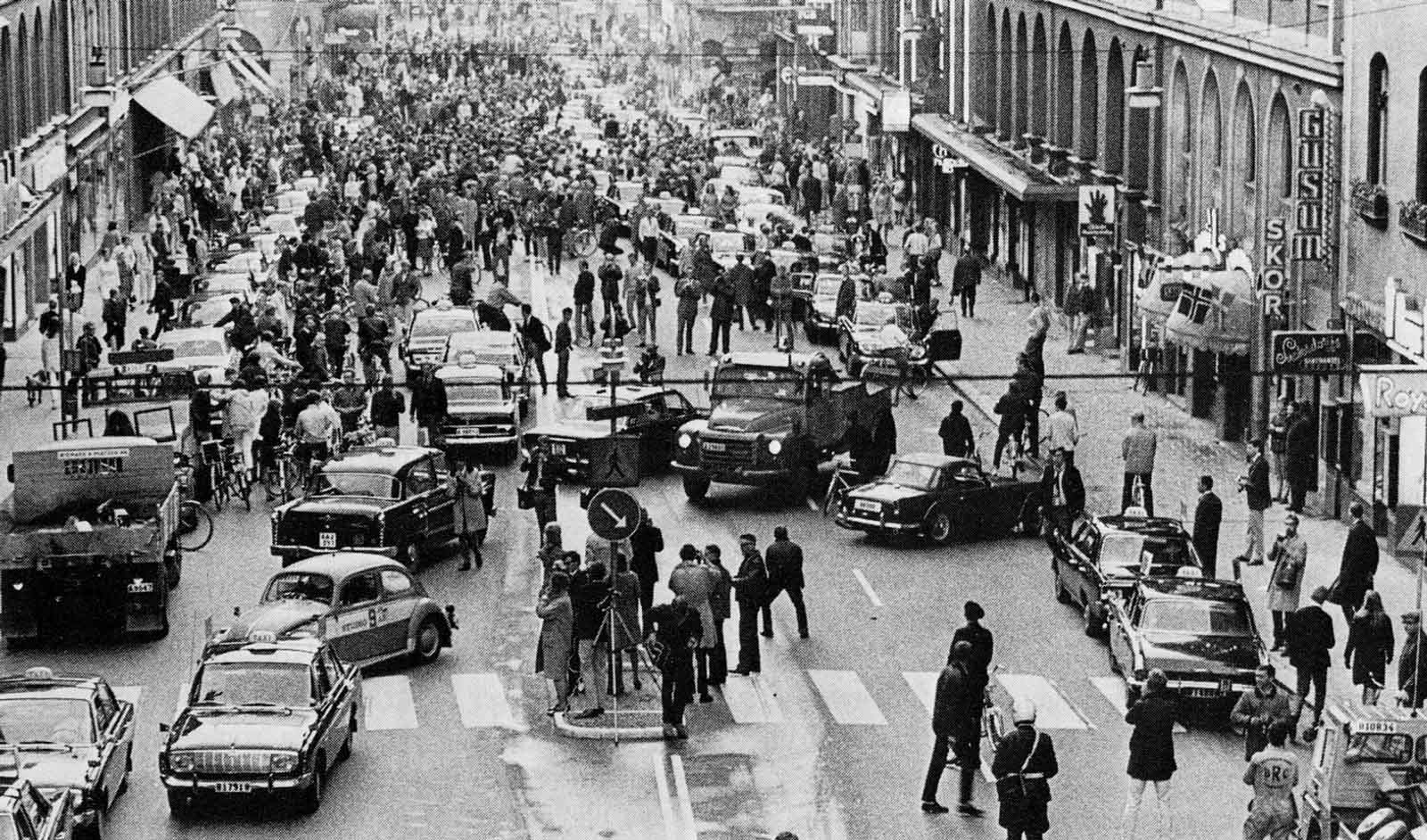

Thanks to all the planning and preparation, the transition went surprisingly smoothly despite widespread public nerves.

Dagen H: September 3, 1967

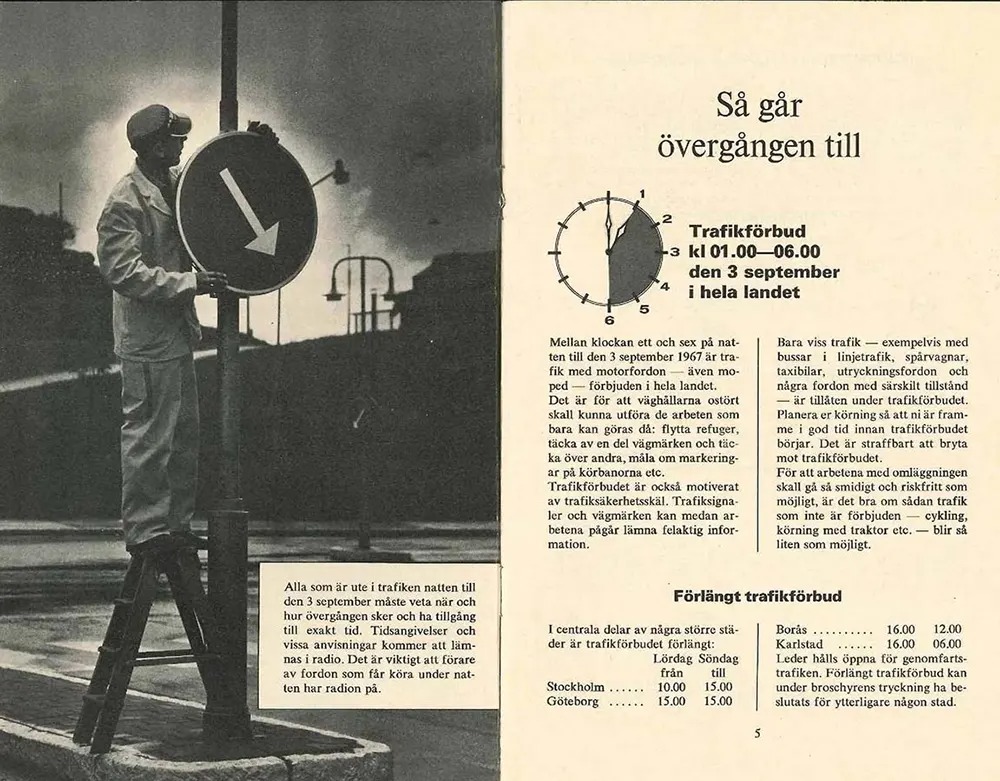

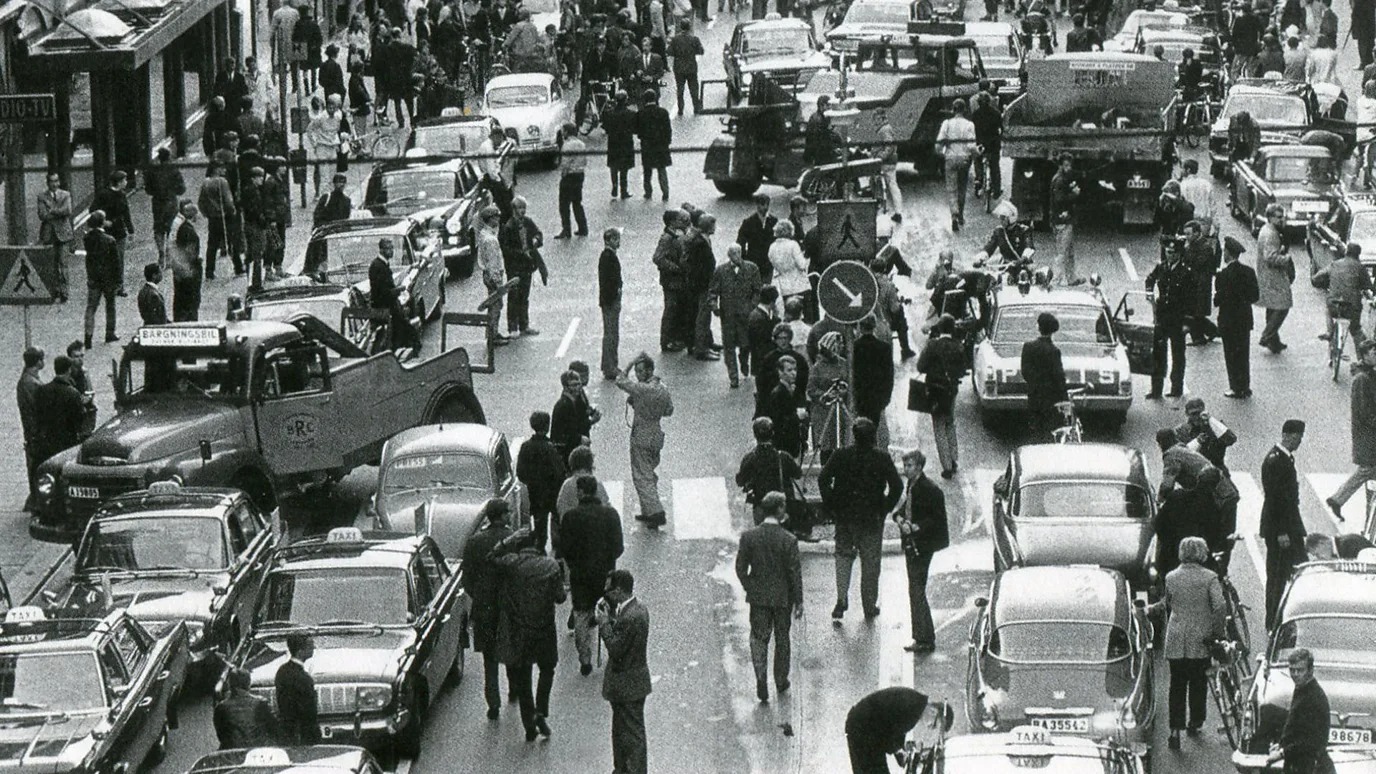

On the morning of September 3, 1967, all non-essential traffic was banned between 1:00 AM and 6:00 AM to allow the final preparations to take place.

At exactly 4:50 AM, all vehicles came to a complete stop, and drivers were instructed to switch to the right side of the road carefully.

Traffic did not resume until 5:00 AM, marking the official start of right-hand driving in Sweden.

In Stockholm and Malmö, the ban lasted even longer—from 10:00 AM on Saturday until 3:00 PM on Sunday—due to the complexity of reconfiguring intersections in larger cities.

There was no serious chaos. In fact, only 157 minor accidents were reported across the country on Dagen H, with just 32 involving personal injury. None of the accidents were fatal, which was a huge success considering the scale of the change.

Immediate Impact: A Safer Sweden?

The day after Dagen H, Swedes cautiously returned to the roads, carefully adjusting to the new right-hand driving system. The number of accidents dropped significantly.

On the Monday following the switch, only 125 traffic accidents were reported, compared to the usual 130 to 198 on a typical Monday.

In the following years, overtaking accidents sharply declined, and there were fewer fatalities and car-to-pedestrian incidents. Motor insurance claims even fell by 40%.

However, three years after the switch, accident rates returned to their previous levels as drivers grew more comfortable and less cautious with the new system.

How Public Reacted

Even though Dagen H went smoothly, it remained controversial, especially because of its high cost. The total cost of the switch was 628 million kronor, roughly $316 million in today’s terms.

Many people criticized the government for pushing through such an expensive project, especially after a majority had voted against it in the 1955 referendum.

However, the government defended the decision, arguing that the benefits far outweighed the costs.

By switching to the right side of the road, Sweden reduced the risk of head-on collisions, made cross-border travel with neighboring countries easier, and aligned with international traffic standards.

As Olof Palme, then Swedish Minister of Communications, stated, “Never before has a country invested so much personal labor and money to achieve uniform international traffic rules.”

A Model for Future Traffic Reforms

Dagen H is still considered one of the most ambitious and well-organized public projects ever. Its success has made it a model for other countries thinking about traffic reforms.

Economic historian Lars Magnusson noted, “It was a fairly cheap transfer in a sense—it was not a very big sum even at that time.” The meticulous planning and execution prevented the chaos many had feared.

In 1997, Sweden launched Vision Zero, an ambitious plan to eliminate all road fatalities. The legacy of Dagen H helped set the foundation for this, and today, Sweden has one of the lowest road death rates in the world.

In 2016, there were only 270 road deaths, a huge drop from the over 1,300 deaths recorded in 1966, the year before the switch.