Ruby Bridges: The First Child To Break The Color Barrier In A White School At Six

On the road to Civil Rights, even children like six-year-old Ruby Bridges became symbols of change. In 1960, Ruby Bridges made history as the first Black student to attend the all-white William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans.

Her brave steps put her at the center of the civil rights movement, but the reality she faced was heartbreaking.

“They would bring this tiny baby’s coffin and put a Black doll inside of it,” Ruby Bridges painfully recalled. “They would march around the school with this coffin, and I would have to pass them to get inside the building. It stuck with me for a very, very long time.”

Let’s delve into the story of Ruby Bridges, the courageous little girl who desegregated a white elementary school in the South.

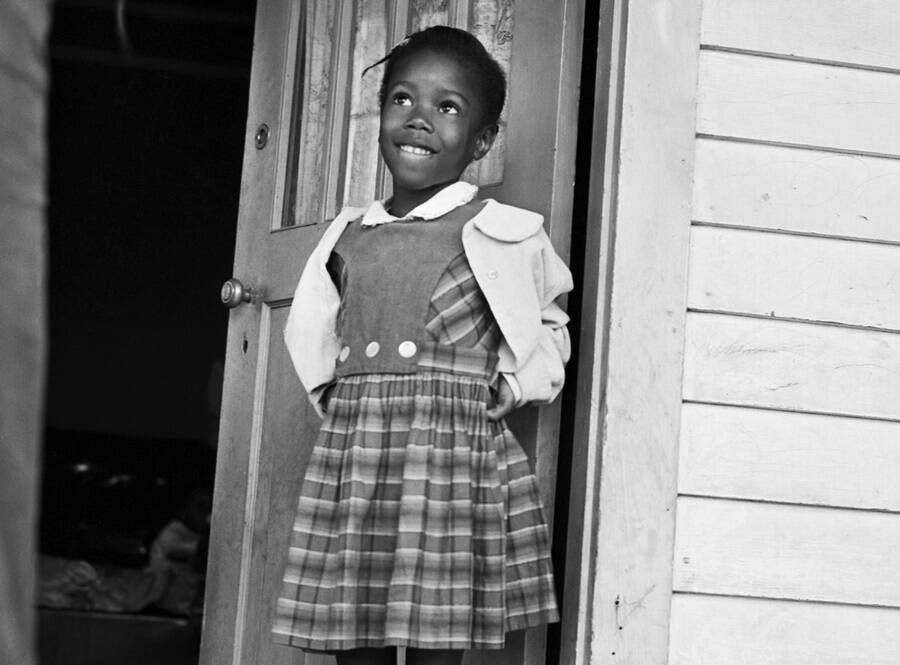

The little Ruby Bridges

Ruby Bridges was born on September 8, 1954, to Lucille and Abon Bridges, who worked as farmers in Tylertown, Mississippi. Just a few months before her birth, the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education legally ended racial segregation in public schools.

When Ruby was four years old, her family moved to New Orleans in search of better opportunities. Her father found work as a gas station attendant, while her mother took on night jobs to support their growing family.

Despite the Brown v. Board ruling, many schools, including those in New Orleans, remained segregated. Though Ruby lived just five blocks from an all-white school, she had to attend kindergarten at a segregated Black school several miles away.

In 1956, under pressure from Black families in New Orleans, Judge J. Skelly Wright ordered the desegregation of the city’s schools.

Segregationists in the government fought back, but despite their efforts, they couldn’t stop progress entirely. They did, however, succeed in requiring Black students to apply for transfers to white schools, a tactic intended to slow desegregation.

Ruby Bridges was one of six Black children in New Orleans to pass a challenging test designed to limit their access to all-white schools. However, two of the children dropped out when the day came to attend, and three others were assigned to a different school.

This left Ruby to face the daunting challenge alone as the sole Black student integrating William Frantz Elementary School.

The day she took a bold step

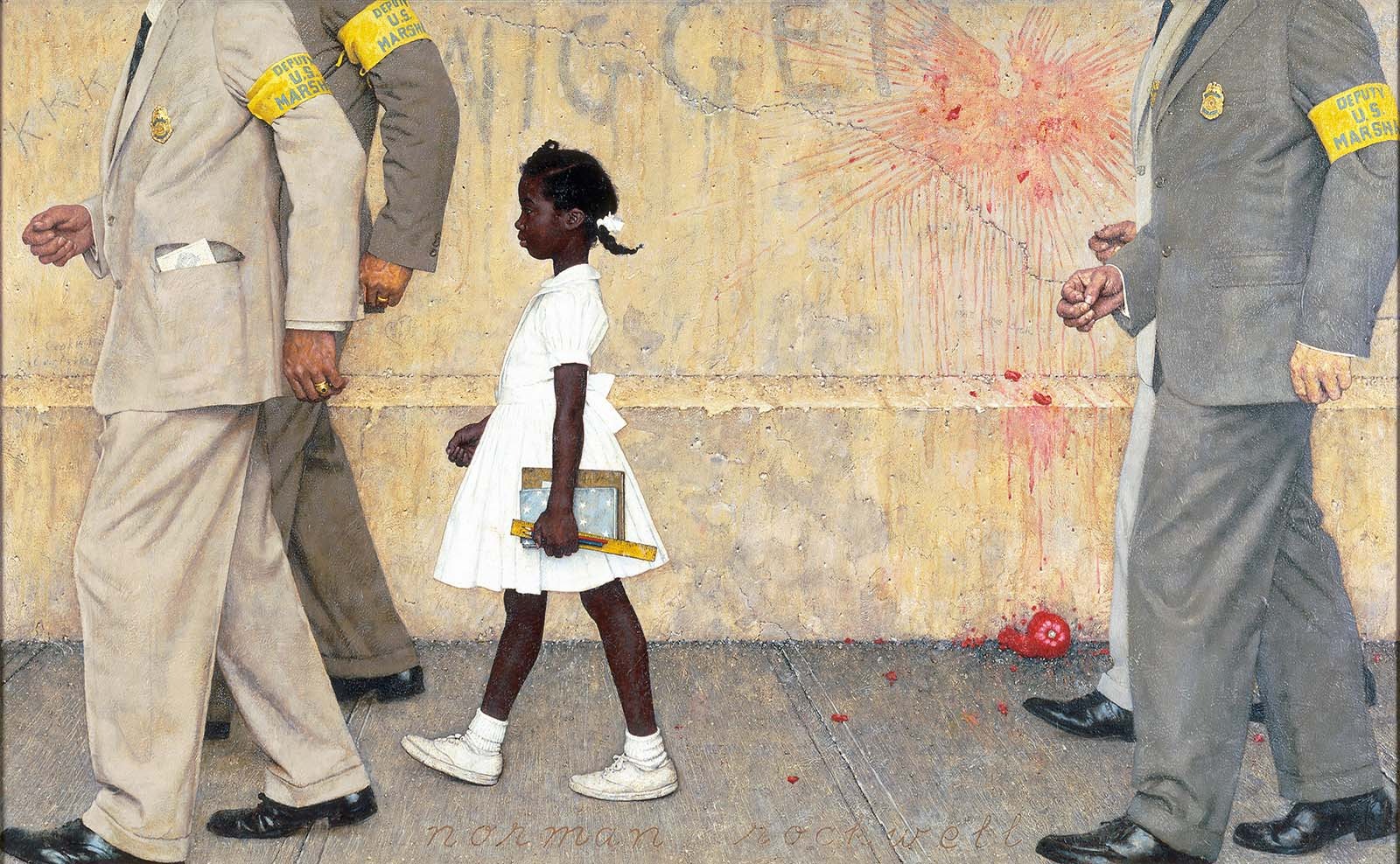

On the morning of November 14, 1960, Ruby Bridges, just six years old, was driven to her new school by federal marshals. They escorted her and her mother to William Frantz Elementary School.

In the car, one of the marshals explained that when they arrived, two marshals would walk in front of Ruby and two behind her to ensure her safety.

This powerful image of a small Black girl being escorted by four white men later inspired Norman Rockwell to paint “The Problem We All Must Live With,” which appeared on the cover of Look magazine in 1964.

Ruby, barely old enough to grasp the significance of the situation, recalled, “I saw barricades and police officers and just people everywhere… I immediately thought that it was Mardi Gras. I had no idea that they were here to keep me out of the school.”

Once Ruby entered the school, chaos ensued. White parents pulled their children out, and all the teachers refused to teach while a Black child was enrolled.

Only one teacher, Barbara Henry from Boston, Massachusetts, agreed to teach Ruby, treating her as if she were teaching a full classroom.

That first day, Ruby and the adults with her spent the entire time in the principal’s office, unable to move to the classroom due to the turmoil in the school.

On her second day, when Ruby finally reached her classroom, she found herself alone in an empty building.

“By the time I got back the second day and was escorted to my classroom,” Ruby remembered, “the building was totally empty. And I remember thinking, you know, my mom has brought me to school too early.”

The protests weren’t limited to the parents; all the teachers except Barbara Henry had also left. For over a year, Henry taught Ruby alone, with the little girl constantly wondering why she was the only child in the entire school.

What happened later

Ruby Bridges made it through that tumultuous first year at William Frantz Elementary. By the time she entered second grade, things had begun to settle down. Her class now included other students, mostly white but also a few Black children.

The once angry crowds outside the school had finally disappeared as the civil rights movement gained momentum throughout the 1960s.

The Bridges family paid a heavy price for their decision to send Ruby to William Frantz Elementary. Her father lost his job, their local grocery store refused to serve them, and her grandparents, who were sharecroppers in Mississippi, were forced off their land.

However, Ruby has also spoken about the support her family received from both Black and white members of the community.

Some white families continued to send their children to William Frantz despite the protests, a neighbor helped her father find a new job, and local people watched over the family, babysat, and even walked behind the marshals’ car as Ruby made her way to school.

Ruby graduated from a desegregated high school, became a travel agent, married, and raised four sons.

In the mid-1990s, she was reunited with her first teacher, Barbara Henry, and the two even did speaking engagements together, sharing their powerful story.

Her enduring legacy

The story of six-year-old Ruby Bridges is one of the most iconic moments from America’s civil rights movement. However, Ruby wasn’t the first Black student to desegregate a school in the Jim Crow South.

A few years earlier, in 1957, nine Black students, known as the Little Rock Nine, enrolled in an all-white high school in Little Rock, Arkansas. Like Ruby, they faced intense racism.

Although Ruby Bridges wasn’t the first to challenge segregation, her story resonated deeply with civil rights activists, especially given her young age.

Her bravery at just six years old made a profound impact. Ruby’s experience inspired numerous films and documentaries, including a 1998 TV movie that bears her name.

Ruby wrote about her early experiences in two books, which earned her the Carter G. Woodson Book Award.

As a lifelong advocate for racial equality, she founded The Ruby Bridges Foundation in 1999 to promote tolerance and change through education.

In 2000, Ruby was honored as an honorary deputy marshal at a ceremony in Washington, D.C.