6 Secretly WWII Spies That Definitely Surprise You

War creates unexpected heroes and secretive operatives. In wartime, anyone can become a spy, even celebrities.

During WWII, some of the most famous figures known for acting, writing, and cooking played crucial roles in gathering intelligence and supporting the war effort.

Have you ever wondered what secrets lie behind their public identities? Let’s explore the surprising espionage activities of these remarkable people.

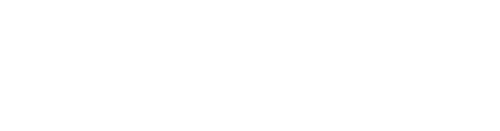

1. Morris “Moe” Berg, a major league baseball player turned secret agent.

Morris “Moe” Berg (1902-1972) was an American catcher in Major League Baseball from 1926 to 1939. Later, he became a spy for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during World War II.

Ted Williams, Hall of Fame baseball player, on Moe Berg: “Moe was the strangest man ever to play baseball.”

After graduating from Princeton in 1923, he began his baseball career as a catcher, playing for several teams, including the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Boston Red Sox.

Though he was often a benchwarmer, his sharp intellect and knack for languages earned him the nickname “brainiest guy in baseball.” Berg was fluent in German, Japanese, French, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese and had some knowledge of at least a dozen other languages.

Nicholas Dawidoff, author of “The Catcher Was a Spy,” described Berg’s intelligence work: “He had this unique combination of physical courage and linguistic brilliance that made him perfect for espionage.”

In his off-seasons, he got a law degree from Columbia in 1928 and worked at a Wall Street law firm while still playing baseball.

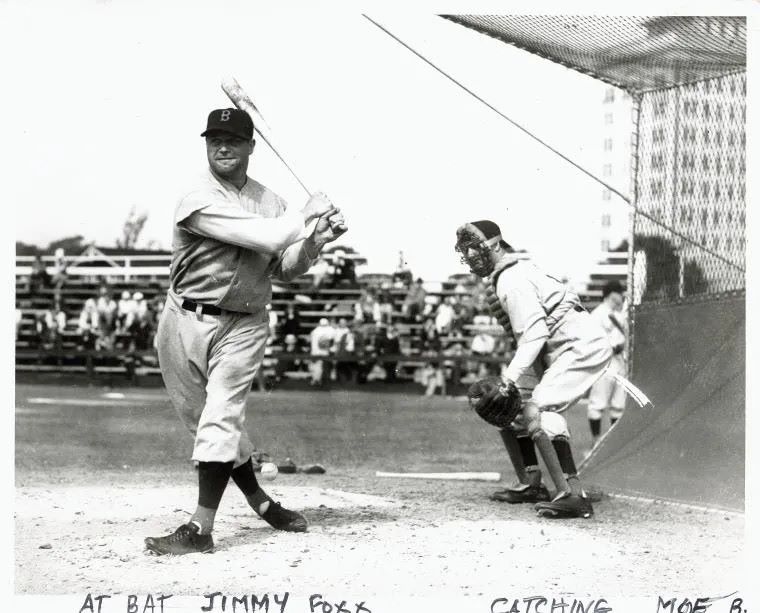

In the 1930s, Berg visited Japan twice, ostensibly for baseball. During these trips, he filmed panoramic views of Tokyo, footage believed to have been used in planning the 1942 Doolittle Raid, America’s first bombing raid on Japan during WWII.

After his trips to Japan, Berg joined the Boston Red Sox in 1935, his fifth and final team. Upon retiring in 1939, he moved into coaching and looked for ways to support the war effort.

Thanks to his language skills and quick wit, he was recruited by the OSS to spy on the atomic bomb program. He was assigned to “Project Larson,” which aimed to interview top Italian physicists about the German bomb program.

In 1944, Berg traveled to Italy and met with physicists Edoardo Amaldi and Gian Carlo Wick. They revealed that they had not conducted any atomic research for the Germans and believed it would take the Germans at least a decade to develop an atomic bomb.

Berg continued meeting other Italian scientists throughout the summer but didn’t learn much about the German nuclear program.

In December 1944, the OSS discovered that German physicist Werner Heisenberg was traveling to Zurich for a lecture. Berg was ordered to attend and contact Heisenberg.

If Heisenberg hinted that the Germans were building a bomb, Berg was to shoot him, even if it meant doing so in the lecture hall.

On December 18, Berg attended the lecture, a pistol in his pocket and a cyanide tablet at hand. Heisenberg did not mention any bomb project during his talk.

Later, Berg dined with Heisenberg and his Swiss host, Paul Scherrer, but found no evidence that the Germans were developing an atomic bomb.

Berg returned to the United States on April 25, 1945, and resigned from the Strategic Services Unit (the OSS’s successor) in August.

After the war, Berg declined several offers to coach Major League Baseball teams. In 1952, the CIA hired him to use his wartime connections to gather information on Soviet atomic science, but he didn’t find much.

Berg spent the rest of his life living with friends and family and died in Belleville, New Jersey, on May 29, 1972.

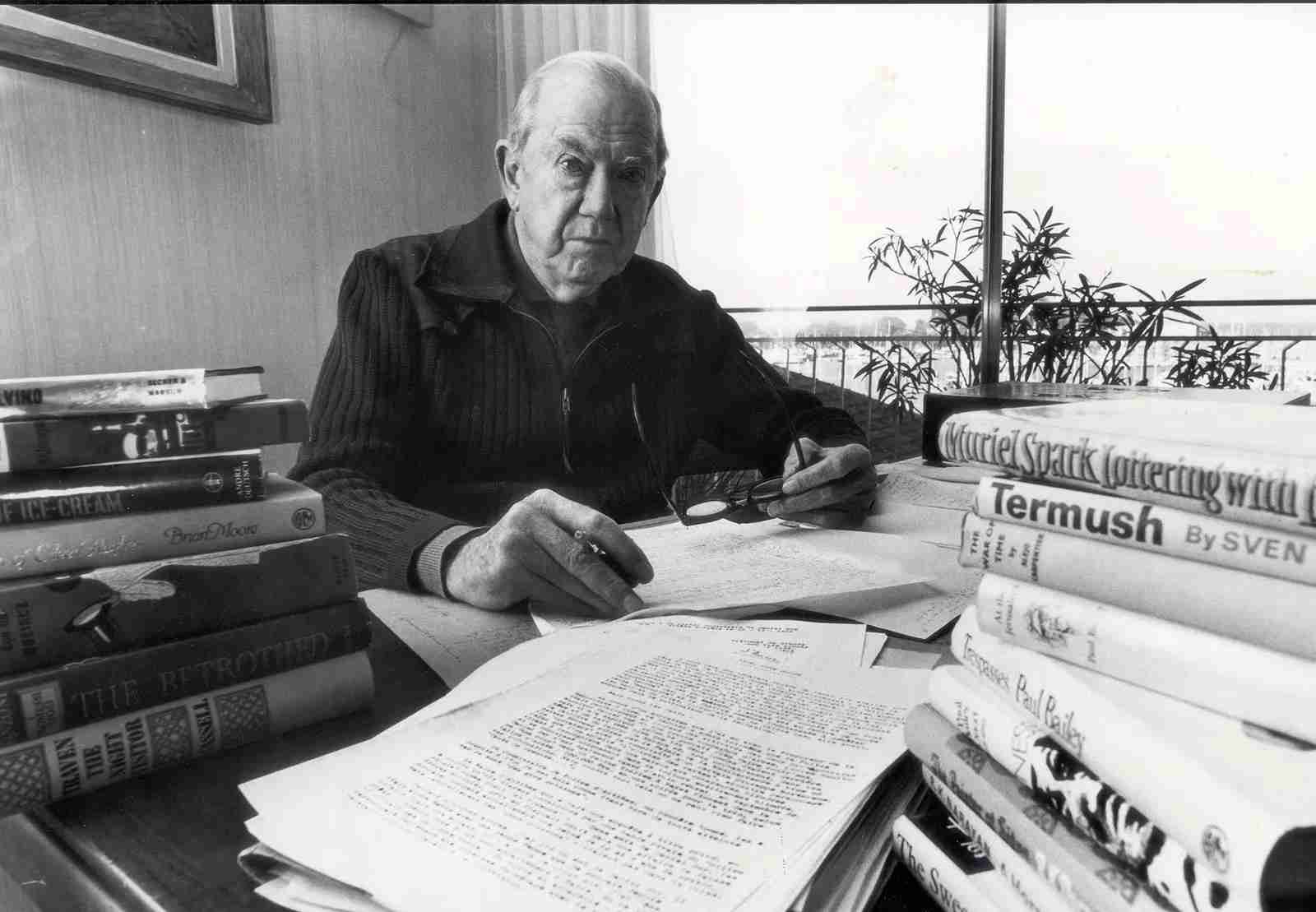

2. Graham Greene, the famed novelist, worked for Britain’s MI6.

“There is a splinter of ice in the heart,” Graham Greene once said, comparing spies to novelists. Both roles, he believed, require a cold, detached view of human struggles and tragedy. Greene would know, as he was both a famous English novelist and an MI6 spy during World War II.

Born in Hertfordshire, Greene came from a notable family, including famous writer Robert Louis Stevenson. Despite this, Greene had a troubled childhood, facing bullying and depression and even attempting suicide. After studying history at Oxford, he worked as a journalist, novelist, and spy.

Greene loved travel and adventure. One biographer described him as a man who loved “drink, opium, adventure, and beautiful women.”

Greene’s travels, often funded by his journalism, inspired many of his works. His trip to Liberia led to the travel book Journey Without Maps, and a trip to Mexico inspired The Power and the Glory, which he considered one of his best novels.

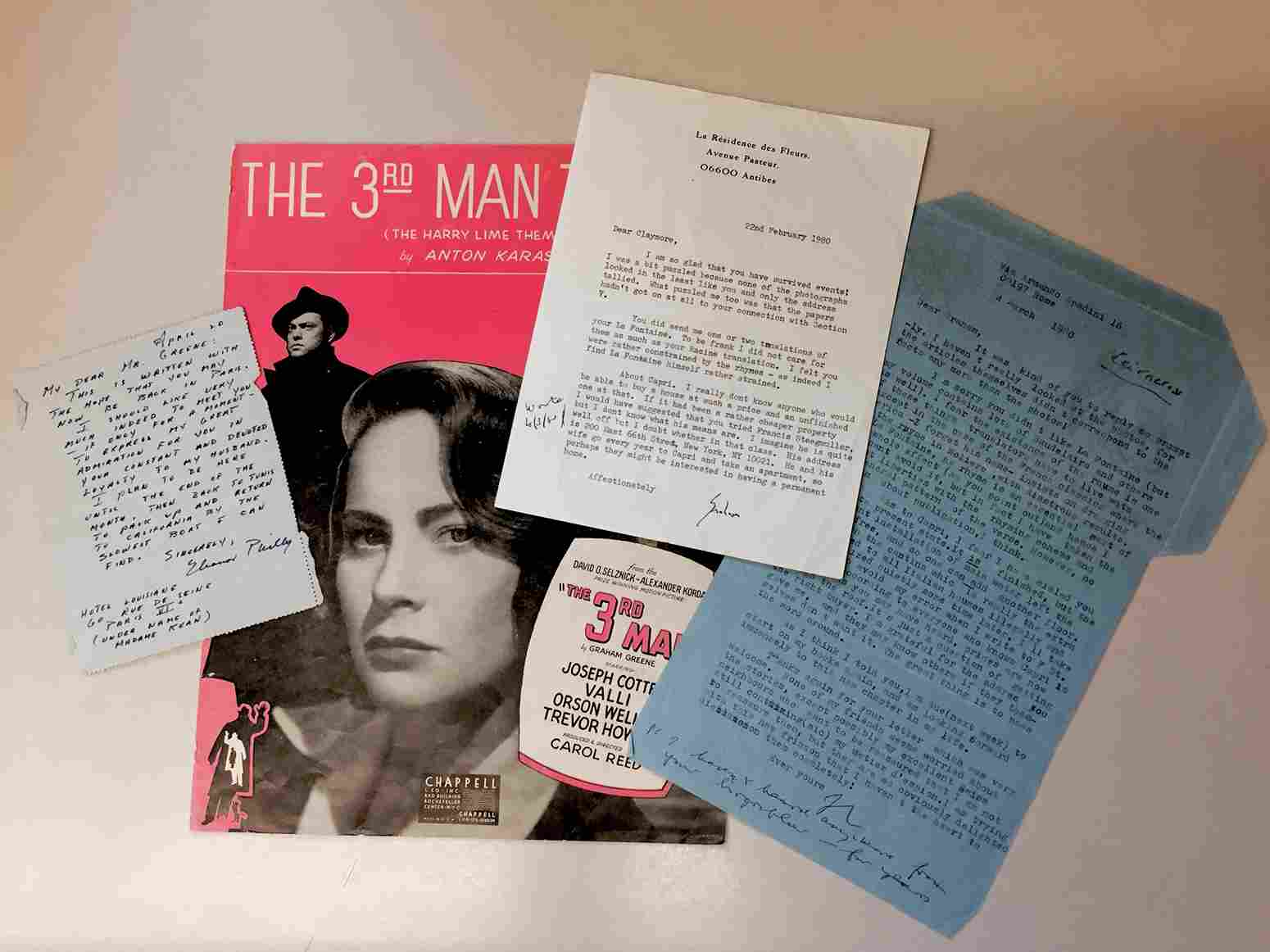

In 1941, Greene’s sister recruited him into MI6. During the war, he served in Sierra Leone, and these experiences influenced his writing, including the screenplay for the film noir The Third Man. While researching the film in war-torn Vienna, he met key figures who would shape his story.

One of Greene’s MI6 contacts, Harry Smollett, was later revealed to be a double agent. Greene’s MI6 supervisor, Kim Philby, was also a notorious double agent, part of the Cambridge Five who spied for the Soviet Union.

In 1957, just months after Fidel Castro began his final revolutionary assault on the Batista regime in Cuba, Greene reportedly helped Castro’s revolution by secretly transporting warm clothes to rebels.

Greene had left intelligence work and moved to France, then Switzerland, where he died in 1991.

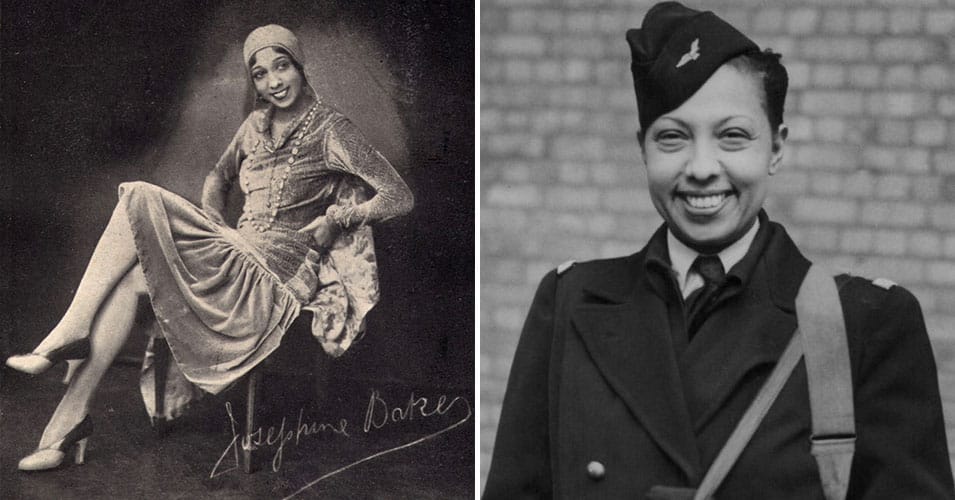

3. The Jazz Age legend Josephine Baker was a covert agent for the French Resistance.

Born Freda Josephine McDonald in 1906 in St. Louis, Josephine Baker grew up poor and married for the first time in her early teens. A talented dancer, she toured the United States with vaudeville troupes and performed on Broadway.

In 1925, she moved to Paris and quickly became a sensation in the city’s music halls. Known as the Black Venus, she also sang and acted in movies, becoming a major European celebrity and a symbol of the Jazz Age.

During World War II, Baker’s disdain for Nazi racism and her gratitude to France led her to join the French Resistance as a spy. Her career allowed her to travel across Europe without raising suspicion.

Josephine was confident in her connections, charming powerful men who never suspected her espionage activities. She attended embassy parties, gathering military and political information to aid the Resistance.

Baker cleverly smuggled secrets by writing them in invisible ink on her sheet music. She also used her chateau in southern France to hide Jewish refugees and store weapons for the Resistance.

Despite living in constant danger and nearly being arrested several times, she always managed to charm her way out of trouble, even when Nazis searched her home. Had she been caught, Baker faced the threat of imprisonment in a concentration camp or worse.

After the war, Baker was honored with several awards from France for her bravery. She remained active in the American civil rights movement but continued living in France with her 12 adopted children, whom she called her Rainbow Tribe.

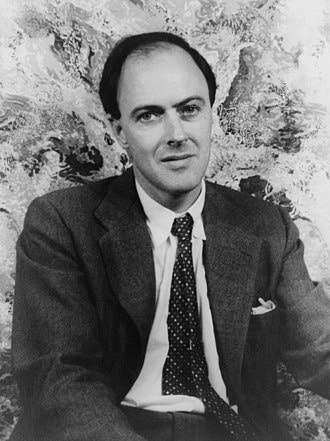

4. Roald Dahl, the best-selling children’s author, spied on the United States.

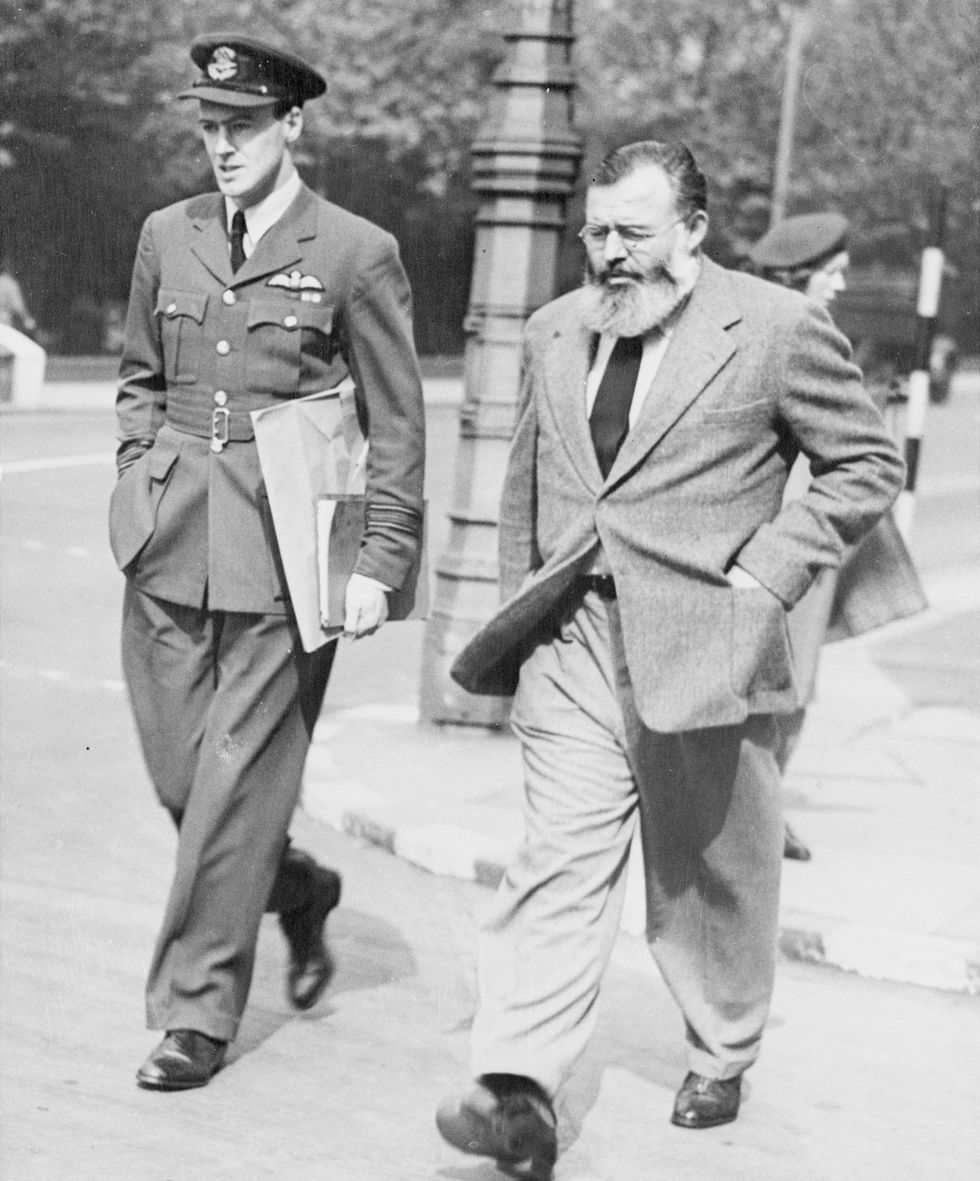

Before becoming famous for “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” and “James and the Giant Peach”, Roald Dahl served as a spy in Washington, D.C. Born in Wales, he joined the Royal Air Force in 1939 and trained as a fighter pilot.

During World War II, he piloted a Hawker Hurricane, flying several combat missions. However, his flying career ended after he was injured in a crash landing in the North African desert.

In 1942, Dahl was appointed assistant air attaché at the British embassy in Washington. There, he joined a spy network called the British Security Coordination (BSC).

This group, which included future James Bond creator Ian Fleming, worked to persuade the United States to join the war against Germany. They planted propaganda and conducted covert activities to influence American opinion.

Even after the U.S. entered the war following Pearl Harbor, BSC agents continued to promote British interests and counter isolationist attitudes.

As an undercover agent, the tall and charming Dahl gathered intelligence by befriending important people in Washington.

Bill Colby (former CIA Director) said, “Roald Dahl was, in many ways, the perfect spy. His charm, wit, and ability to connect with people from all walks of life made him invaluable during the war.”

He met politicians, journalists, business leaders, socialites, and even first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, using his connections to collect valuable information about the U.S. political scene.

Tommy Hitchcock Jr. (American diplomat and fellow BSC agent) talked about Dahl “Dahl had a knack for getting people to trust him. He could blend into any environment and make everyone feel at ease, which was a rare and useful talent in our line of work.”

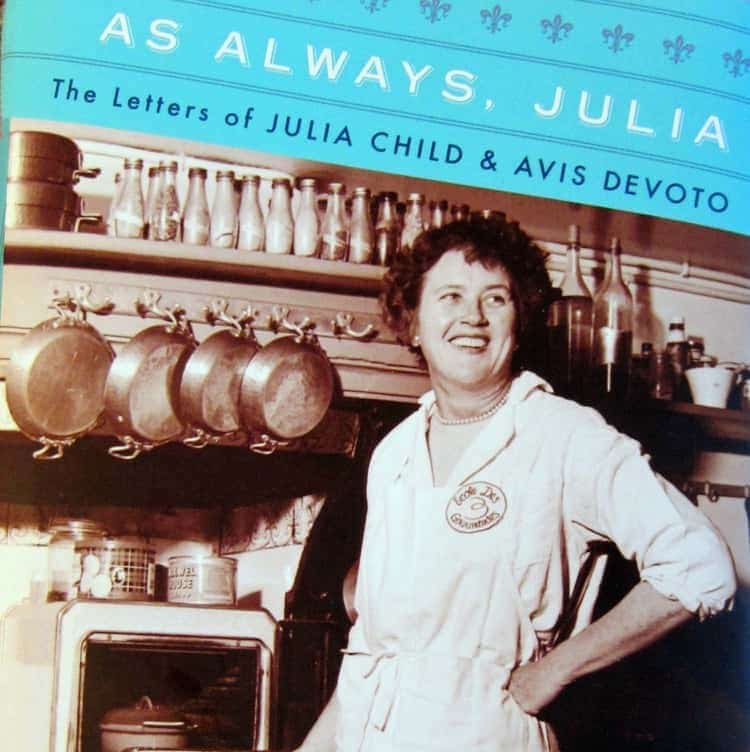

5. TV chef Julia Child once handled top-secret documents.

Julia Child, best known for popularizing French cuisine in America, also had a fascinating career as a spy.

Julia’s first culinary experiences came as the chair of the Refreshment Committee for Senior Prom and Fall Dance. After graduating from Smith College in 1934, she wrote advertising copy for a furniture store in New York City.

When the United States entered World War II, Julia wanted to serve her country. She was too tall to join the military at 6’2″, so she volunteered for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the CIA. Julia was one of 4,500 women who served in the OSS.

Julia worked directly for the OSS’s leader, General William J. Donovan, in its headquarters in Washington.

She worked as a research assistant in the Secret Intelligence branch, typing hundreds of names on small white note cards, a system used to keep track of officers before the advent of computers.

Julia then worked with the OSS Emergency Sea Rescue Equipment Section, developing shark repellent to protect explosives targeting German U-boats. Curious sharks would sometimes trigger the explosives, so the repellent was crucial.

From 1944-1945, Julia was stationed in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and Kunming, China, serving as Chief of the OSS Registry.

She had top security clearance and handled every incoming and outgoing message, dealing with highly classified information about the invasion of the Malay Peninsula. Despite the danger, Julia found the work fascinating.

Air Force intelligence officer Byron Martin admired her dedication and intellect and described her as “a person of unquestioned loyalty, of rock-solid integrity, of unblemished lifestyle, and of keen intelligence.”

While Julia’s cooking career left a mark on American history with her enthusiastic TV presence and cookbooks, her contributions to the OSS are remembered. Julia passed away at 91 in 2004, just two days before her 92nd birthday.

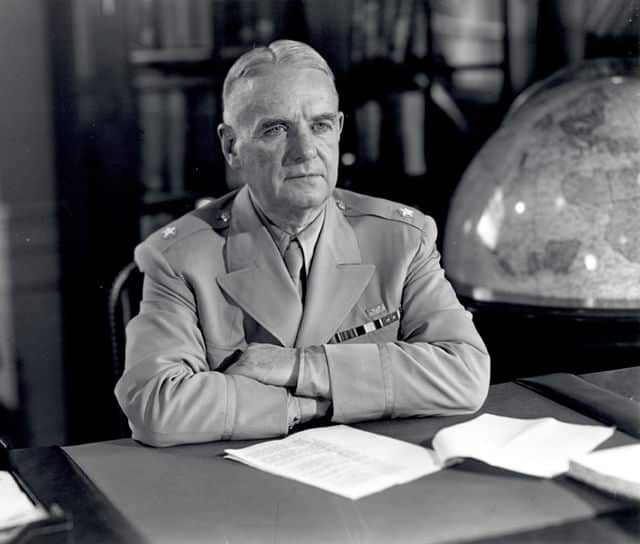

6. Arthur Goldberg, the intelligence operative, turned U.S. Supreme Court justice.

During World War II, Arthur Goldberg, who would later become a Supreme Court justice, worked for the OSS, setting up an intelligence network with anti-Nazi groups in Europe.

Born in Chicago to a Russian immigrant, Goldberg graduated from Northwestern University Law School. He paused his law career to join the Army during the war. Not physically fit enough to join the Marines, he served in the Army, rising to the rank of major.

In the OSS, Goldberg organized an information-gathering network behind enemy lines in Europe.

The Jewish Telegraphic Agency stated, “Goldberg’s file notes that as both a civilian and a member of the Army, he supervised a section in the Secret Intelligence Branch of OSS to maintain contact with labor groups and organizations regarded as potential resistance elements in enemy-occupied and enemy countries. He organized anti-Nazi European transportation workers into an extensive intelligence network.”

After the OSS was disbanded by President Harry Truman in 1945, Goldberg became a leading labor attorney. In 1961, President John Kennedy appointed him as U.S. Secretary of Labor, and the next year, Kennedy named him to the Supreme Court.

However, in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson convinced him to resign from the court to become the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations.

After leaving his UN post in 1968, he unsuccessfully ran for governor of New York in 1970, then continued practicing law and advocating for human rights.