The 1924 Democratic National Convention: A Marathon Of Chaos In U.S. Political History

The 1924 Democratic National Convention is a remarkable chapter in U.S. history. It was featured by record-breaking length, numerous ballots, and deep internal divisions.

Held at Madison Square Garden, the event showcased significant conflicts over Prohibition and the Ku Klux Klan’s influence. Despite the chaos and violent clashes, this convention set the stage for future political realignments.

Why was the 1924 Democratic National Convention the longest and most chaotic in U.S. history? Keep scrolling to understand the complexities of this historical event.

Unprecedented duration and numerous ballots

The 1924 Democratic National Convention ran for 16 days, from June 24 to July 9, making it the longest in U.S. history. It took 103 ballots to nominate John W. Davis, reflecting the intense struggle among delegates.

This chaotic atmosphere was famously remarked upon by humorist Will Rogers, who said, “I belong to no organized party. I’m a Democrat.” The event remains notable for its length and the sheer effort required to reach a consensus.

Significant factional conflicts

Starting on June 24, 1924, the Democratic National Convention in New York City was a hot and tense event. Initially hopeful due to divisions in the Republican Party, Democrats quickly realized their own deep fractures.

The party was a mix of diverse groups: Northerners, Southerners, Catholics, Jews, Protestants, and more. Key issues like prohibition and the Ku Klux Klan caused major rifts.

Al Smith, New York’s Catholic governor, opposed prohibition and clashed with Southern and Western Democrats. William Gibbs McAdoo, a Protestant and prohibition supporter, refused to condemn the Klan, alienating Northeastern Catholics and Jews. This deep cultural divide defined the chaotic convention.

The Ku Klux Klan intensifying divisions

The Ku Klux Klan’s popularity surged after World War I, bolstered by their support of Prohibition. By the mid-1920s, they had gained influence in both the Republican and Democratic parties.

At the 1924 Democratic Convention, tensions between pro- and anti-Klan factions led to violent clashes. Pro-Klan delegates backed William Gibbs McAdoo, while anti-Klan delegates, led by Senator Oscar Underwood, sought to condemn the Klan’s violence in the party platform but narrowly failed.

Al Smith, a Catholic and anti-prohibition candidate, symbolized the deep cultural divide within the party.

The Klan’s opposition to Smith, due to his religion and stance on Prohibition, further inflamed tensions. McAdoo, who quietly courted Klan support, found his base in the rural South and West, while Smith represented the urban, diverse Northeast.

These divisions led to fights at the convention and throughout New York, with violent demonstrations like the effigy burning of Smith by 20,000 Klan members.

Historian Robert K. Murray detailed these events in “The 103rd Ballot: Democrats and the Disaster in Madison Square Garden”.

Physical altercations and heated debates

Even before voting began, partisan animosity among Democrats permeated every aspect of the convention. The famous songwriter Irving Berlin wrote a pro-Smith song, “We’ll All Go Voting for Al,” instead of an anthem of party unity.

In Madison Square Garden, rival factions chanted “Mac, Mac, McAdoo” and “Smith, Smith, Alfred Smith,” leading to fights on the floor. Both McAdoo and Smith needed 732 votes to win, but neither could secure enough support, resulting in a prolonged deadlock.

After 99 ballots, both candidates told their supporters to vote freely, paving the way for John W. Davis to emerge as the nominee on the 103rd ballot.

Journalist H.L. Mencken commented on the absurdity of the convention, “The delegates kept on voting for their pets as before, like children poll-parroting a meaningless rhyme. It was an idiotic and depressing spectacle.”

He continued, “If you can imagine 3,000 dogs in one great pit, all frantically chasing their tails, you can imagine what it looked like.”

Democrats’ loss in the 1924 election

Though Davis was a compromise candidate, his nomination did little to heal the party’s rifts. McAdoo blamed his loss on Tammany Hall, while Smith believed the Ku Klux Klan and his Catholicism hurt his chances, as he received almost no Southern votes.

By the time Davis secured the nomination, the excitement at Madison Square Garden had faded. Fundamentalist Democrats like William Jennings Bryan and liberals distrusted Davis’ Wall Street ties.

This led Senator Robert La Follette to run independently as a progressive candidate. The Democratic Party’s internal conflicts and the chaotic convention, which was broadcast nationwide, damaged their electoral chances.

A degrading article about how “Davis as a boy was afraid of girls” appeared in The Boston Globe. It was said that the Democratic nominee for president had “no plans for the immediate future, other than to obtain a needed rest.”

“This was certainly an embarrassment because it was the first convention that was broadcast on radio,” according to Historian Lewis. “So people could tune in and hear all of the folderol.”

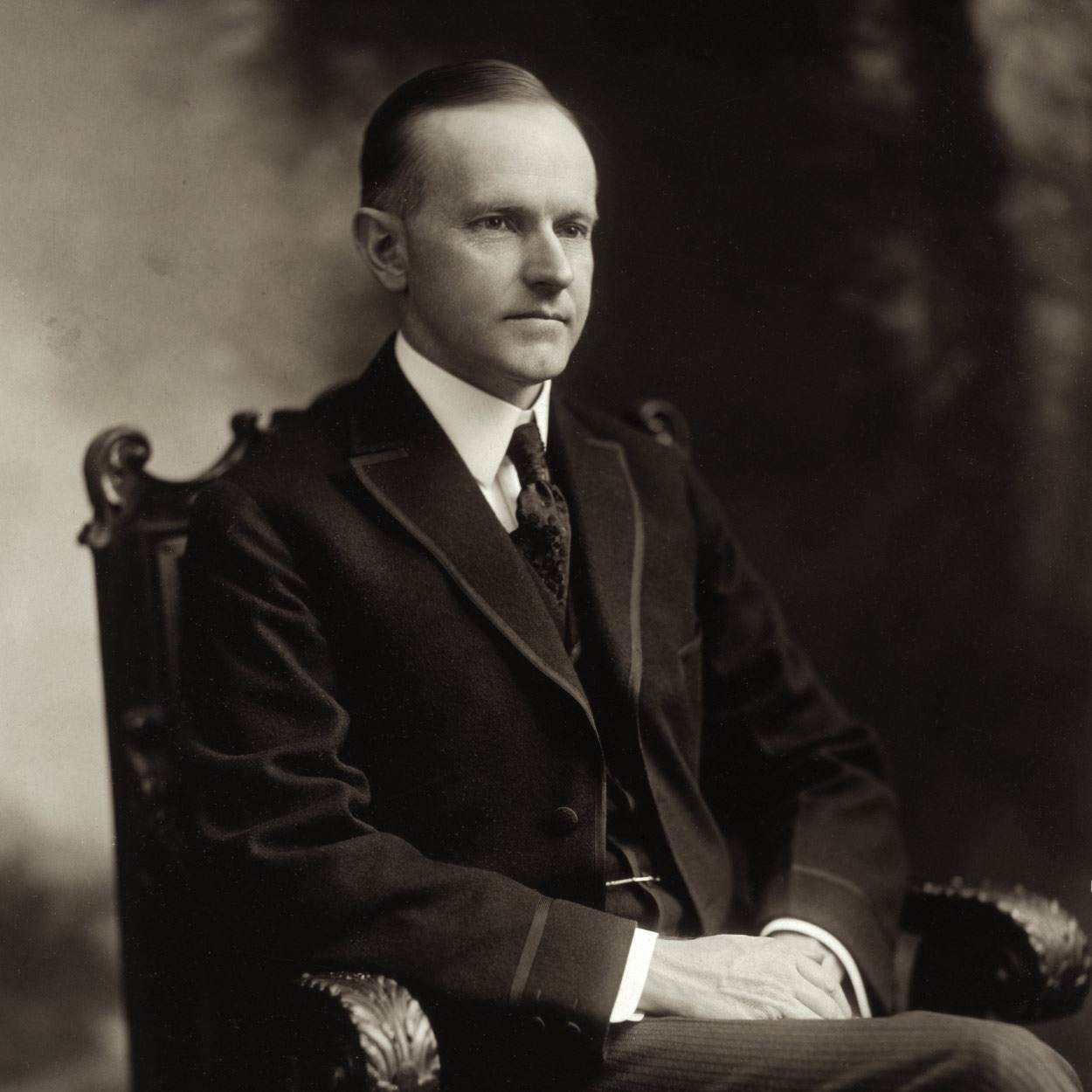

In the 1924 election, the Democrats lost badly to Calvin Coolidge. The Republicans’ slogan “Coolidge or chaos” resonated with voters. Davis only managed to win 12 states and 29% of the popular vote, while Coolidge secured 54% in the three-way race against Davis and La Follette.

Reflecting on the Democrats’ defeat was seen as a result of their internal conflicts and poor choices. “They got what they deserve,” Lewis commented on the Democrats’ loss. “That’s a terrible thing to say, yes. [But] they created this conflict, and they chose poorly.”

Legacy of the 1924 DNC

The 1924 Democratic National Convention, despite its disorganization and ultimate failure, offers lessons for today’s Democrats.

The Ku Klux Klan’s influence and the Democrats’ election loss sped up party realignment, leading to significant future changes like Al Smith’s 1928 nomination and FDR’s New Deal coalition.

The convention saw the first Black delegate, A.P. Collins, and the first women considered for vice president. Lewis highlights resistance figures like Erwin, whose legacy of speaking against the Klan continues to inspire.

One of Erwin’s notable quotes, shared by his grandson Milton Leathers in 2017, still resonates:

“I say that those Georgians who do not take a stand against this hooded menace, which prowls in the darkness, that dares not show its face, is not worthy of his ancestry; and I call upon you, my fellow Georgians, … to purge from your hearts this senseless prejudice.”